Summary

Child marriage, defined as marriage before the age of 18, has been associated with a wide array of poor economic, social, and health outcomes for women and their children. It was estimated in 2014, however, that around half of all prime-aged women living in South Asia and in Sub-Saharan Africa were married as children.

This post summarizes a recent article, which has demonstrated that aggregate economic shocks have sizable effects on the age of marriage of women living in developing countries. The study focuses on Sub-Saharan Africa, where it is customary for the groom or his family to pay a bride price to the bride’s family, and India, where the bride’s family traditionally pays a dowry to the groom or his family.

In a simple model of child marriage, families with sons or daughters choose when their children marry, women move to the groom’s family upon marriage, and sons partly support their family. After a temporary aggregate negative income shock, budgets are tight and households have a higher marginal utility of consumption. Consequently, they prefer to bring forward (with bride price) or delay (with dowry) the marriage of their daughters so that they can consume the marriage payment.

We use rainfall data to identify incidences of drought, which is shown to lead to 4–5% drop in aggregate income. We then relate the occurrence of droughts over a woman’s early years to the timing of marriage, taken from the Demographics and Health Surveys from 31 countries, which cover around 400,000 women born between 1950 and 1989. We find that, as our theory predicts, droughts have opposite effects on the timing of marriage in Sub-Saharan Africa and in India. In Sub-Saharan Africa, the bride price region, a drought raises the annual probability of entering marriage between ages 12 and 17 by 3%. In India, where dowries prevail, a drought decreases the probability by 4%. These findings are robust to a wide set of alternative definitions of rainfall shocks and alternative sample specifications.

The relationship between droughts and early marriage can also have significant demographic consequences: in Sub-Saharan Africa, experiencing an episode of drought during the teenage years increases the total number of children a woman reports by 0.06 or 1%. These effects are not observed in India.

These results have important policy implications for the battle to curb child marriage: the effect that transfers to the families of adolescent girls will have on marriage and teenage pregnancy is likely to depend on the traditional marriage practices in place within the country or ethnic groups. Unconditional cash transfer programs may help to decrease child marriage where bride price prevails, but may have the opposite effect in countries where dowry payments are customary. We conjecture that conditional cash transfers may be more effective in communities with a tradition of dowry payments.

More generally, our findings point to the importance of culture and institutions in influencing how people respond to economic shocks and policies, and therefore highlight the value of replicating experimental and quasi-experimental analyses in different contexts.

Main article

Child marriage is associated with a wide array of poor socio-economic outcomes, but around half of all prime-aged women in South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa were married as children. A recent article demonstrates that economic shocks have a sizeable impact on the age of marriage, though the effect depends on the direction of marriage payments. In Sub-Saharan Africa, where bride prices are common, drought (which causes negative income shocks) increases the probability of child marriage. In India, where dowries are traditional, the opposite effect prevails. This implies that unconditional cash transfers may decrease child marriage in communities with a tradition of bride prices, but are likely to have the opposite effect where dowries are more common.

Child marriage, defined as marriage before the age of 18, is a widespread phenomenon in many parts of the world. About half of all prime-aged women living today in South Asia and in Sub-Saharan Africa were married as children (UNICEF 2014). Child marriage has been associated with a wide array of poor economic, social, and health outcomes for women and their children (see, among others, Field and Ambrus 2008).

New paper suggests that economic shocks – like COVID-19 – have a significant impact on child marriage

This post summarizes a recent article, in which we show that aggregate economic shocks have sizable effects on the age of marriage of women living in developing countries (Corno, Hildebrandt and Voena 2020). This is a vitally important insight—understanding the economic forces that influence the age of marriage can inform the design of policies to combat child marriage and may therefore have significant economic and demographic benefits.

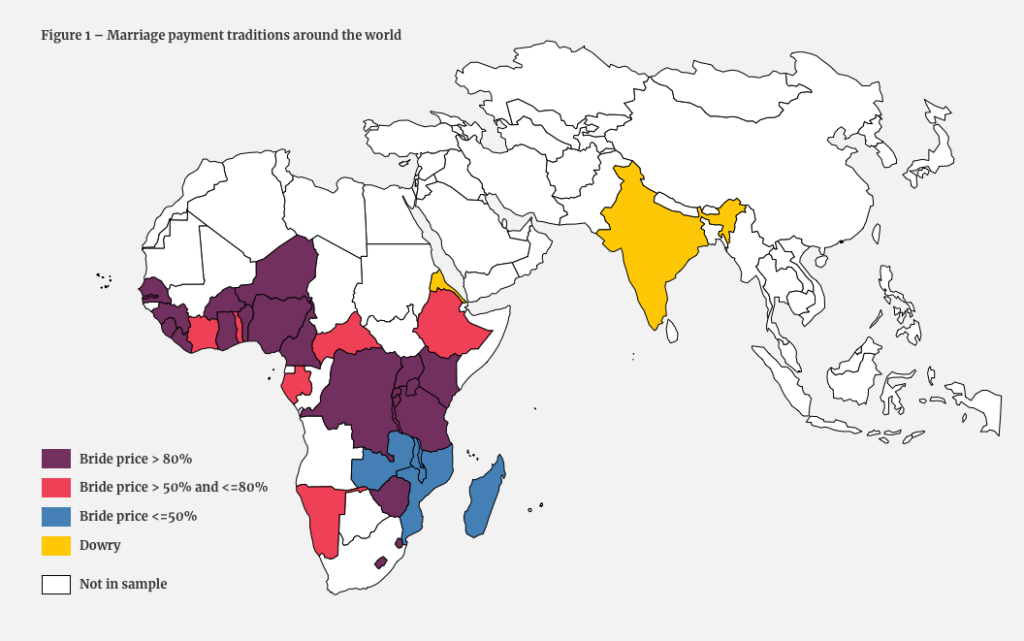

We study two regions of the world, Sub-Saharan Africa and India, where traditional marriage payments persist. Throughout Sub-Saharan Africa, it is customary for the groom or his family to pay a bride price to the bride’s family. In India, on the other hand, the prevailing tradition is for the bride’s family to pay a dowry to the groom or his family at the time of marriage (Figure 1). We study how these traditions influence the timing of marriage when income shocks occur.

Figure 1 – Marriage payment traditions around the world

Notes: Marriage payment traditions in our sample from the Atlas of Pre-Colonial Societies (Muller et al. 2010). Figure B1 from Corno, Hildebrandt and Voena (2020).

We begin by developing a simple model of child marriage, in which families with sons or daughters choose when their children marry, women move to the groom’s family upon marriage, and sons partly support their family. After a temporary aggregate negative income shock, budgets are tight and households have a higher marginal utility of consumption. Consequently, they prefer to bring forward (with bride price) or delay (with dowry) the marriage of their daughters to consume the marriage payment. At the same time, they prefer to postpone (with bride price) or bring forward (with dowry) the marriage of their son. In equilibrium, bride prices or dowry payments (prices) fall, and child marriages (quantities) increase under bride price and decrease under dowry as long as the parents of a son benefit from his earnings even after he gets married.

The research suggests that negative income shocks raise the annual probability of marriage for women under 18 in Sub-Saharan Africa

Empirical results

Guided by the predictions of the model, we measure the relationship between child marriage and aggregate income shocks, combining rainfall data from the University of Delaware Air Temperature and Precipitation project (UDel) with information on the age of marriage from the Demographic and Health Surveys from 31 Sub-Saharan African countries and India, which cover approximately 400,000 women born between 1950 and 1989.

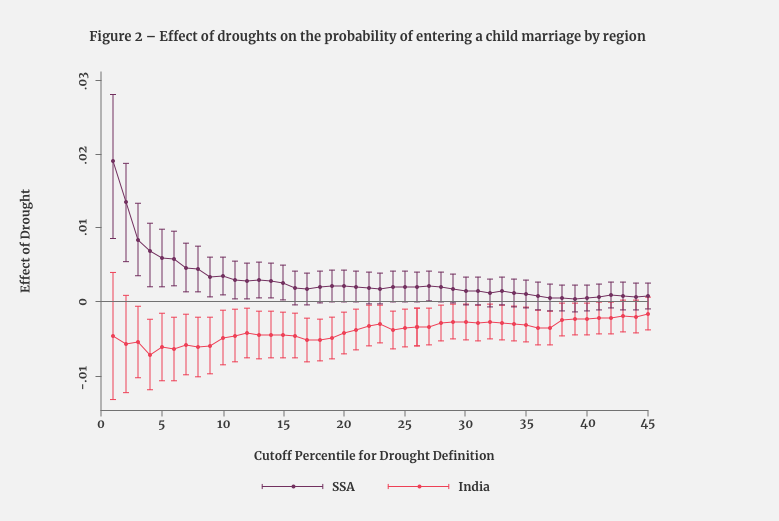

Within each local area in these regions, we construct a measure of drought, which corresponds to an annual rainfall realization below the 15th percentile of the local distribution (Burke, Gong and Jones 2015). We show that droughts lead to a 10 to 15% decline in agricultural production and a 4 to 5% drop in aggregate income in both regions. When we relate the occurrence of droughts over a woman’s early years to the timing of marriage, we find that, as our theory predicts, droughts have opposite effects on the timing of marriage in Sub-Saharan Africa and in India. In Sub-Saharan Africa, the bride price region, a drought raises the annual probability of entering marriage between ages 12 and 17 by 3%. In India, where dowries prevail, a drought decreases the probability by 4%. These findings are robust to a wide set of alternative definitions of rainfall shocks and alternative sample specifications. As shown in Figure 2, any definition of drought as a low realization of rainfall is associated with an increase in the probability of a child marriage in Sub-Saharan Africa and a decrease in India.

Figure 2 – Effect of droughts on the probability of entering a child marriage by region

Notes: Figure 2 from Corno, Hildebrandt and Voena (2020) shows the point estimates of the effect of droughts on early marriages, estimated using OLS regressions for the Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) and India full regression samples: women aged 25 or older at the time of interview. The different points represent different definitions of drought based on the percentile of rainfall in a grid cell (SSA) or district (India) in a given year, relative to the fitted long run rainfall (gamma) distribution in that grid cell or district. The capped spikes show the 95% confidence intervals of the estimated coefficients.

The relationship between droughts and early marriage can also have significant demographic consequences: in Sub-Saharan Africa, the occurrence of a drought is also associated with a 4% increase in the annual probability of having a child before turning 18, and experiencing an episode of drought during the teenage years increases the total number of children a woman reports by 0.06 or 1%. These effects are not observed in India.

The findings suggest that negative income shocks make dowry payment more difficult in India, and therefore decrease the probability of child marriage

Variation between and within countries can help us establish whether the presence of marriage payments and their direction can explain the sign of the effects that we uncover. In Sub-Saharan Africa, we find that the positive effect of droughts on the probability of entering into child marriage only prevails within those countries and ethnic groups that traditionally pay bride price at marriage, and not in those where bride price is not a historical tradition. Similarly, in India, we find no effects of droughts for the oldest cohorts in the South of the country, where dowry was more recently introduced, but a sizable effect for more recent cohorts.

Discussion

These results have important policy implications for the battle to curb child marriage: the effect of transfers targeting adolescent girls and their families on marriage and teenage pregnancy is likely to depend on the traditional marriage practices in place within their country or ethnic groups. Unconditional cash transfer programs may help to decrease child marriage where bride price prevails, but may have the opposite effect in countries where dowry payments are customary. We conjecture that conditional cash transfers may be more effective in communities with a tradition of dowry payments.

Sub-Saharan African women who experience drought as teenagers will, on average, start having children younger and have more children in total

Our findings are particularly salient in the current economic climate. Although data on the precise impact of COVID-19 in the developing world is still sparse, it is likely that many countries will see a significant economic contraction. Policy makers should be prepared for the fact that—without intervention—this may filter through into a sizable increase in child marriages in developing countries with a tradition of bride prices.

More generally, our findings point to the importance of culture and institutions in influencing how people respond to economic shocks and policies. Findings from a natural experiment in one institutional setting may not be valid elsewhere.

Our results therefore highlight the value of replicating experimental and quasi-experimental analyses in different contexts in order, under the guidance of economic theory, to improve our understanding of the mechanisms behind empirical results.

This article summarizes ‘Age of marriage, weather shocks, and the direction of marriage payments’ by Lucia Corno, Nicole Hildebrandt, and Alessandra Voena, published in Econometrica in May 2020.

Lucia Corno is at the Department of Economics and Finance, Cattolica University, and LEAP). Nicole Hildebrandt works for the Boston Consulting Group in New York. Alessandra Voena is at the Department of Economics at Stanford University and is affiliated with NBER, CEPR, and BREAD.