Summary

Empirical evidence suggests that labor markets have become more concentrated since the late 20th century, shifting from a large number of small employers toward a smaller number of larger employers. Recent academic work has also documented that wages are lower, on average, in more concentrated labor markets.

A new paper uses a decade of US hospital mergers to examine whether this negative relationship between concentration and wages is explained by limited competition causing lower wages, or whether the two are simply correlated. US hospital markets are a fitting setting to study this question. Many of the workers they employ have industry-specific skills, making each hospital merger a potentially meaningful contraction of the employment options available to these workers. The study uses difference-in-differences regressions and event study specifications to compare how hospital workers’ wages evolve in the years following mergers in a local labor market to how wages evolve in other, similar markets that did not have merger activity.

Economic theory makes several predictions about how wages should evolve following an employer merger if employer concentration indeed causally affects wages. First, mergers that induce larger concentration increases should induce larger slowdowns in wage growth. Second, wages of workers who can more easily switch employers should be less affected. Third, wages of workers who have bargaining leverage vis-à-vis their employers should be less affected. This study finds empirical support for each of these theoretical predictions. The authors find wage effects only for workers with the most industry-specific skills, and—even then—only when mergers constituted a substantial increase in employer concentration.

However, mergers may affect wages through other mechanisms beside increased labor market power, such as through managerial changes designed to reduce labor costs. The authors test for this possibility by examining the wage effects of “out-of-market” mergers in which the merging hospitals are located in non-overlapping labor markets, and thus the merger does not affect local labor market concentration. Because the authors can plausibly rule out labor market power effects in these cases a priori, any observed wage impacts following such mergers can instead be attributed to alternative non-labor market power mechanisms. The authors find no changes in wage trajectories following out-of-market mergers, suggesting that their main findings cannot be explained without invoking labor market power.

There are multiple conceivable mechanisms through which concentration can cause low wages, not all of which have the same policy implications. The most familiar mechanism is “classical monopsony”, where an employer can pay wages below the marginal product of labor because it can restrict the number of jobs to below its competitive equilibrium level. There are, however, many mechanisms besides classical monopsony that can result in lower wages as concentration increases, and some—such as a deterioration in exit options reducing employee bargaining leverage—will reduce wages without simultaneously reducing employment. The authors do not find evidence that the mergers in their sample reduced employment, which may indicate that the “classical monopsony” model cannot fully explain labor market dynamics in this case. This implies that regulators should consider a more expansive definition of labor market power, which could require, for example, labeling some mergers that are not thought to reduce the number of jobs as anti-competitive, and looking beyond simple translations of existing tools for detecting product market power into a labor market context.

Main article

Can policies that support labor market competition raise worker pay? Economic theory predicts that workers in labor markets with a few dominant employers will have lower wages. This study looks at US hospital mergers and provides some of the first evidence for a causal link between employer concentration and wages, especially for workers who cannot switch employers easily or who have low bargaining power. These findings suggest that strengthening labor market competition is a plausible path to raising worker pay, and have important implications for how regulators define labor market power.

A combination of empirical facts and economic theory suggest rising employer concentration contributed to wage stagnation in industrialized economies. Economic theory shows how labor market concentration can suppress wages by reducing workers’ bargaining leverage vis-à-vis powerful employers. Empirical evidence suggests that labor markets have become more concentrated since the late 20th century, shifting from a large number of small employers toward a smaller number of larger employers (Autor et al. 2020). Moreover, recent academic work has documented that wages are lower, on average, in more concentrated labor markets (Azar et al. 2017; Benmelech et al. 2019; Qiu and Sojourner, 2019; Rinz 2018).

A new paper offers some of the first empirical evidence that the relationship between increased labor market concentration and lower wages may be causal

However, this negative relationship between concentration and wages does not necessarily imply that limited competition in the labor market causes lower wages, as opposed to merely being correlated with them. This is an important distinction, because if concentration is not the cause of wage stagnation, then policies designed to shore up labor market competition will not raise wages. For such policies to be effective, they must counteract an existing mechanism through which high employer concentration causes low wages.

To see why a negative relationship between labor market concentration and wages does not constitute proof that concentration causes low wages, consider the contrast between a densely populated city and a sparse rural county. The city will have many employers, none of which dominates the labor market by itself. The rural county will have a comparatively small handful of employers, implying higher labor market concentration. The rural county is also likely to have substantially lower average wages, driven in part by a lower cost of living. This will result in a negative correlation between concentration and wages when comparing the county to the city, even if the high labor market concentration in the county did not cause the low wages there. A policy “solution” that attempts to raise wages in the county by breaking up large employers is therefore unlikely to be effective.

The research described here asks whether increases in concentration cause wage stagnation by examining the impacts of employer mergers on wages. When employers merge, labor market concentration increases. As in other settings, higher concentration moves prices further from the perfectly competitive equilibrium. In a product market setting, this entails higher product prices borne by consumers. In a labor market setting, it instead implies lower wages (labor prices) borne by workers. Antitrust regulators in the US are actively considering adding such labor market considerations to merger reviews.

New work sheds light on the circumstances under which policies designed to shore up labor market competition will raise wages

Can Increasing Concentration Cause Wage Stagnation?

To answer the question of whether any portion of the relationship between concentration and wages is causal, we examined the impacts of a decade of hospital mergers in the US on the wages paid to hospital workers in the affected labor markets. US hospital markets are a fitting setting to study this question. Many of the workers they employ have industry-specific skills, making each hospital merger a potentially meaningful contraction of the employment options available to these workers. Indeed, labor markets for nurses are commonly given as textbook examples of employer monopsony. Hospital markets therefore offer an opportunity to look for a “smoking gun” of labor market concentration suppressing wages.

In addition to hospitals’ potential to exert market power over their workers, hospital markets are of interest due to their antitrust enforcement history. Prior to and during our sample period, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) challenged multiple hospital mergers that would substantially increase product market concentration, and lost many of these challenges in court. In a recent case, the FTC—for the first time —cited reductions in worker wages among the purported harms of a proposed merger of two health systems in Texas (FTC 2020).

New research indicates that labor market concentration may only affect the wages of workers with the most industry-specific skills

Our study of hospital mergers used difference-in-differences regressions and event study specifications to compare how hospital workers’ wages evolve in the years following mergers in a local labor market to how wages evolve in other, similar markets that did not have merger activity. We looked for evidence that wages grow more slowly following mergers that increase concentration than they would otherwise. Because an increase in labor market concentration may affect wage-setting at all employers within the market—an employer that does not participate in a local merger can offer its workers smaller raises when those workers now have fewer other employers bidding for their talent—we included in the analysis all hospitals in a given labor market, not just those that participate in mergers. In the labor markets that experience a merger and are included in our sample, 30 percent of hospitals are directly involved in mergers, while the other 70 percent are bystanders to those mergers (i.e., they compete in the same market).

Economic theory makes several predictions about how wages should evolve following an employer merger if employer concentration indeed causally affects wages. First, mergers that induce larger concentration increases should induce larger slowdowns in wage growth. Second, wages of workers who can more easily switch employers should be less affected. Third, wages of workers who have bargaining leverage vis-à-vis their employers should be less affected. We found empirical support for each of these theoretical predictions in the data. Other recent studies provide additional evidence on some of these predictions (Arnold 2021); Benmelech et al. 2019).

To test the first prediction, we checked whether wages grow slower following mergers that substantially increase concentration than following mergers that only moderately increase concentration or than in the absence of mergers. We divided the 84 hospital mergers in our sample period into quartiles based on the labor market concentration change they induced, as measured by the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI). We found effects of mergers on wages only in the top quartile of HHI increases, where the average HHI increase is 2,764 when considering a narrow definition of the labor market (hospitals in the same commuting zone) and 790 when considering a more expansive definition (all health care employers in the same commuting zone).

A new study indicates that mergers may only negatively affect wages where they result in a substantial increase in employer concentration

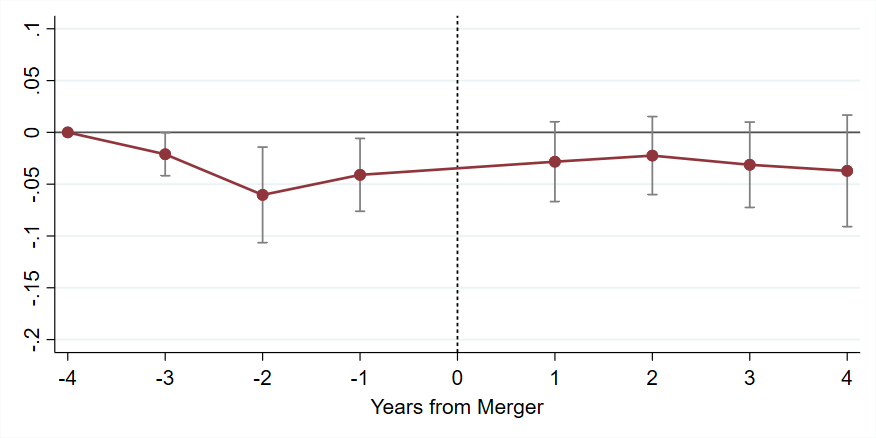

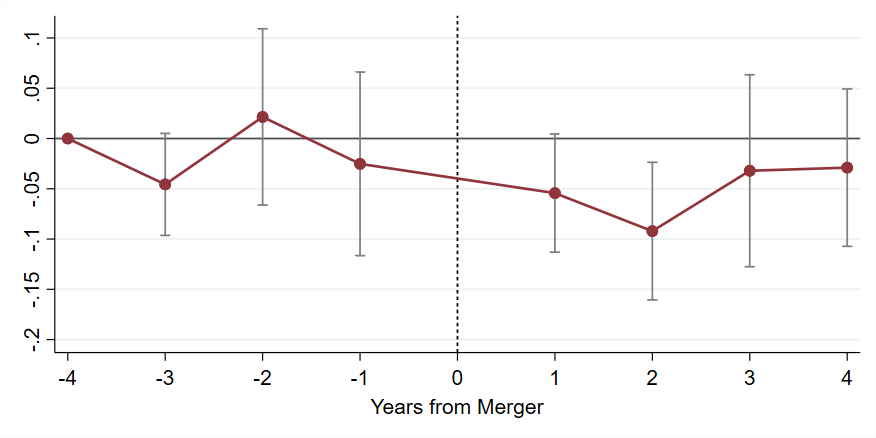

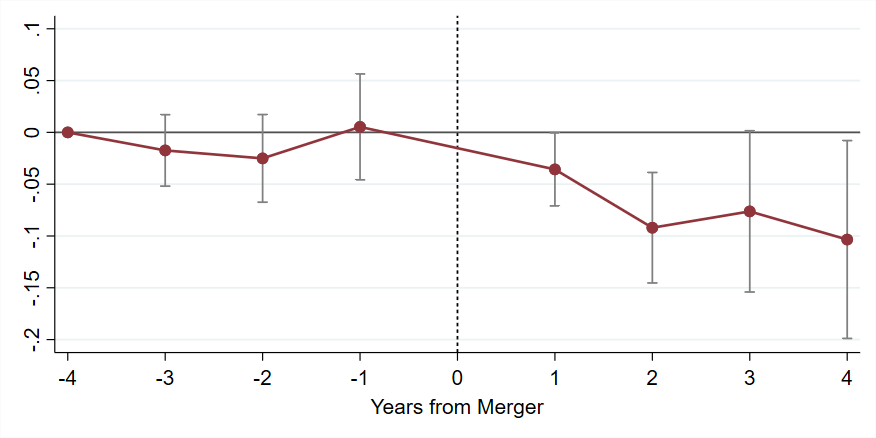

The second prediction is that wages will be more strongly affected for workers who are less easily able to switch employers and/or industries. To test this prediction, we examined wage trajectories separately as a function of workers’ formal training level and the industry specificity of their job. We grouped workers into three categories: workers with little formal training and whose job tasks are generally not specific to the hospital industry, such as cafeteria workers; skilled workers in non-medical occupations, such as workers in the employee benefits department; and skilled health care professionals, specifically nursing and pharmacy workers. For generalist workers who are presumably least tied to the hospital industry, we did not find evidence that concentration-increasing mergers slow down wage growth (Exhibit 1). For the two categories of skilled workers, we found evidence of reduced wage growth, but only in cases where the concentration increase induced by the merger was large. Measured over the four years following the merger, for the top quartile of concentration-increasing mergers, we estimated that wages are 4.0 percent lower for skilled non-health professionals and 6.8 percent lower for nursing and pharmacy workers than they would have been absent the merger. These estimates represent wage growth reductions of more than 25 percent of baseline wage growth rates.

Exhibit 1: Leads and Lag Estimates – Top Quartile of Mergers by change in HHI

Panel A. Unskilled wage

Panel B. Skilled wage

Panel C. Nursing and pharmacy wage

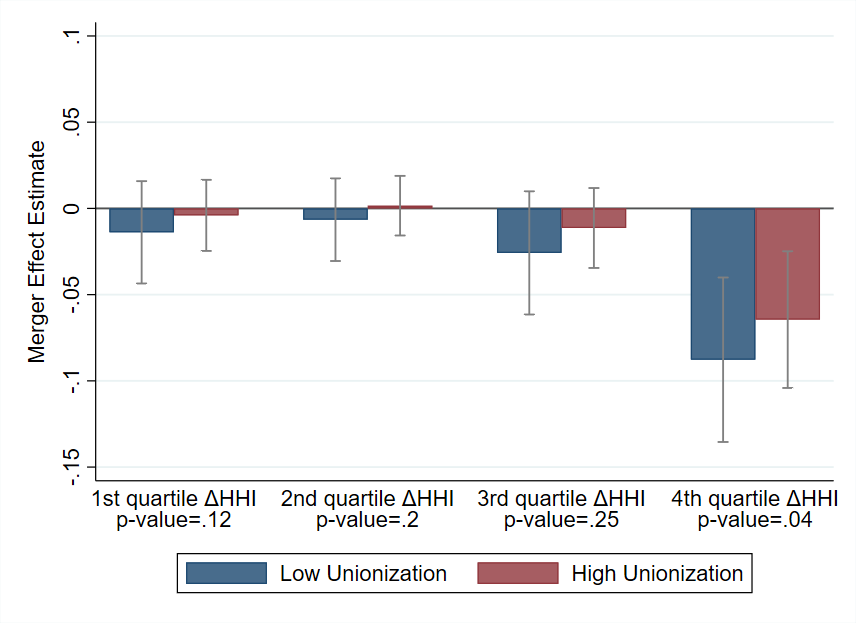

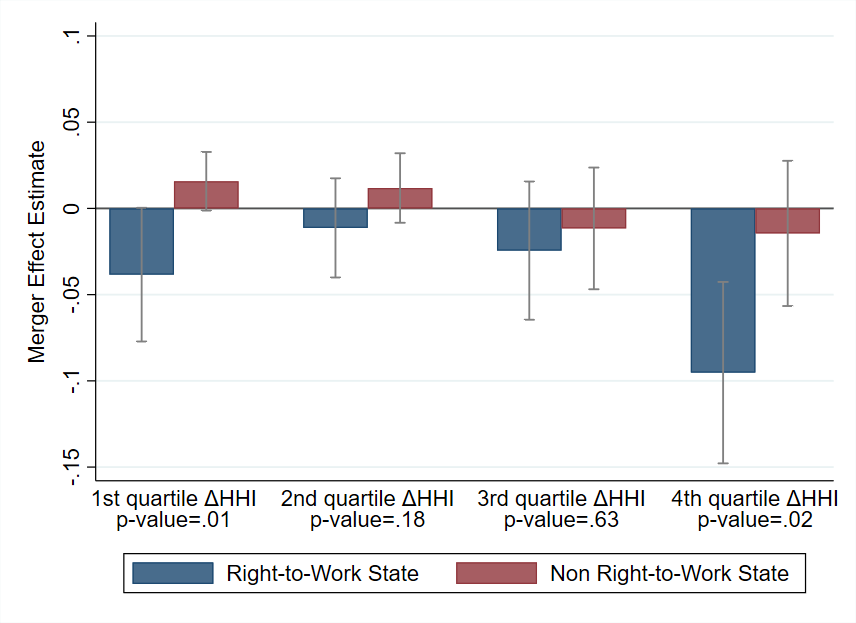

The third prediction is that wages will be less strongly affected by increases in employer concentration, and therefore increases in employer market power, when workers have countervailing power. Although we could not measure worker power directly, we constructed two proxies. We tested this prediction by checking for heterogeneous impacts of mergers on wages as a function of nurse unionization rates (unionized workers have more power than workers who negotiate individually) and the presence of right-to-work laws (right-to-work laws weaken unions). Our estimates indicate that both high levels of unionization and a pro-union environment (as measured by the absence of right-to-work laws) appear to mitigate the estimated negative wage effects (Exhibit 2).

Exhibit 2: Wage effects and labor unions

Panel A. Nurse unionization

Panel B. Right-to-work laws

The results described thus far are consistent with merger-induced increases in labor market power reducing wage growth. We found wage effects only for workers with the most industry-specific skills, and only then when mergers constituted a substantial increase in employer concentration. Nevertheless, mergers may affect wages through other mechanisms, such as managerial changes designed to reduce labor costs. We tested for this possibility by examining the wage effects of “out-of-market” mergers in which the merging hospitals are located in non-overlapping labor markets, and thus the merger does not affect local labor market concentration. Because we can plausibly rule out labor market power effects in these cases a priori, any observed wage impacts following such mergers can instead be attributed to alternative non-labor market power mechanisms. We found no changes in wage trajectories following out-of-market mergers, suggesting that our main findings cannot be explained without invoking labor market power.

Sources of Labor Market Power

There are multiple conceivable mechanisms through which concentration can cause low wages. The one most familiar to antitrust regulators and to readers of introductory economics textbooks, which we call “classical monopsony”, is the labor market analog to a monopolist seller in a product market. In a competitive labor market, employers must compete for workers by offering higher wages or other desirable working conditions. A classical monopsonist is an employer that constitutes workers’ only option. The monopsonist employer can pay a lower wage than the wage that would arise in a competitive labor market. It will attract fewer workers at that lower wage, meaning it will produce fewer revenue-generating products, but that trade-off may be worthwhile if the per-worker wage savings are sufficiently large. In other words, a classical monopsonist’s power to pay wages below the marginal product of labor arises from its ability to restrict employment (i.e., the number of jobs) below its competitive equilibrium level.

Classical monopsony is the direct labor market analog to the monopoly power considerations that antitrust regulators already use to evaluate potentially anticompetitive mergers in product markets. The close parallels make classical monopsony a convenient path for applying antitrust enforcement tools to labor markets. If regulators wish to promote labor market competition, however, then the classical monopsony framework is too narrow. This is because, despite some substantial similarities, labor markets are not exactly analogous to product markets. There are many mechanisms besides classical monopsony that can result in lower wages as concentration increases—mechanisms that regulators may erroneously ignore if they rely solely on the classical monopsony framework.

New research indicates that the “classical monopsony” framework may be too narrow for regulators wishing to promote labor market competition

The labor economics literature suggests a broader conceptualization of labor market power. For example, labor market power can arise from search frictions, a term that refers to the fact that workers must exert effort and expend resources in order to find a new job, allowing their current employer to pay them a slightly lower wage without fear that they will quit. Employer concentration can also drive down wages in cases where workers must bargain over wages with their new or current employers, and a more concentrated labor market reduces the workers’ bargaining leverage because their exit option deteriorates.

What distinguishes these mechanisms from classical monopsony is that, unlike under classical monopsony, we can expect concentration to reduce wages without simultaneously reducing employment. This distinction provides a way to test whether our main findings are attributable to classical monopsony. We looked for evidence to suggest that the mergers in our sample reduced employment. We did not find any, even when we restricted our sample to only those mergers that were found to reduce wage growth. These estimates were noisier than our other findings, however.

Policy Implications

There is value in additional research to determine the prevalence of wage suppression in the absence of employment suppression. If, as our results suggest, such cases are not unusual, then regulators should consider the more expansive definition of labor market power. This would require, for example, labeling as anti-competitive some mergers that are not thought to reduce the number of jobs. It would also require the antitrust agencies to look beyond simple translations of existing tools for detecting product market power into a labor market context. The two key US antitrust agencies—the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) and Department of Justice (DOJ)—are actively considering these questions. We expect labor market issues to remain an important issue in antitrust in the coming years.

This article summarizes ‘Employer Consolidation and Wages: Evidence from Hospitals’ by Elena Prager and Matt Schmitt, published in American Economic Review in February 2021.

Elena Prager is at the Kellogg School of Management at Northwestern University. Matt Schmitt is at Compass Lexecon.