Summary

Asset owners often need to identify and choose between potential contracting partners to monetize their asset’s value. How should an owner go about this process? Decades of economic theory that compared formal transaction mechanisms finds that, in many cases, some kind of auction maximizes seller revenues and ensures the asset is allocated to the partner who valued it the highest. Little is known, however, about how well auctions perform relative to the informal, unstructured processes through which many important assets are allocated in the real world.

We take advantage of a historical wrinkle in land exploitation rights in Texas to empirically investigate the differences in performance between formal and informal mechanisms in the US market for mineral leases. At independence, millions of acres of unsettled Texan land were allocated to a fund. Landowners who purchased their land out of this fund before 1973 were given the right undertake private lease negotiations for minerals located beneath the further of their land on the state’s behalf—in exchange for a share of the proceeds. Those that purchased land after 1973 did not get this right.

Private landowners generally allocate mineral leases through informal negotiations, whereas public owners nearly always allocate mineral leases by conducting centralized and well-publicized auctions. The date at which landowners bought land therefore affects the manner in which minerals are leased on nearly 8 million acres of land across Texas to this day. This unusual situation allows us to compare otherwise equivalent negotiated leases and auctioned leases, something that would be impossible to do in other mineral leasing settings.

In comparing leases signed between 2004 and 2016, we find that negotiated leases would have generated $185,000 more upfront revenue, on average, had they been awarded using an auction. This finding is intuitive; faced with the threat of more competition, it makes sense to expect that E&P companies would bid more in an auction than they offer in a negotiation.

Our analysis also suggests, however, that auctions allocate assets more productively. Auctioned leases produce roughly 50% more output than negotiated leases. Combining discounted royalty payments and up-front bonuses, we estimate that auctions increase total payments to sellers by about $341,000 per lease, on average.

What’s driving these large payment and productivity gains from auctions? Conceptually, it is possible that some firms are persistently more productive than others, but there may also be more idiosyncratic differences that lead some firms to be able to extract more minerals from particular parcels more productively than others. Our data suggests it is the quality of a match between firms and leases, rather than simply the quality of the firm, that is the primary source of the productivity gains we measure. Auctions, it seems, both bring in more competition than negotiations and “pick” better winners.

While it may be possible to help private landowners negotiate better through education and legal representation, policy encouraging auctions in place of negotiations is likely to be less expensive and more effective. Enormous gains could be realized from encouraging this switch across the $3 trillion private mineral leasing market.

Main article

What is the best way to sell something? Theory and experience have demonstrated the virtues of using formal mechanisms, like auctions, to allocate assets. Yet, in the real world, many important assets are allocated using less formal processes. We show that mineral leases in Texas allocated via auction produce significantly more output and generate much larger payments for mineral owners. These results suggest large potential gains from employing centralized, formal mechanisms in markets that traditionally allocate in an unstructured fashion, including the broader $3 trillion market for privately owned minerals.

Asset owners often need to identify and choose between potential contracting partners to monetize their asset’s value. For example, companies that are acquisition targets may have multiple potential acquirers, and research institutions looking to commercialize intellectual property often decide among several interested parties. Many land transactions also look like this. How should an owner go about this process? Decades of economic theory have characterized the relative performance of different formal transaction mechanisms. In many cases, some kind of auction maximizes seller revenues, and ensures that the partner who places the highest value on the asset ends up getting it (Milgrom, 2004).

In the real world, many important assets are allocated via informal, decentralized processes. For example, sellers of homes in the US propose list prices, but then review offers as they come in, committing neither to selling to the first offer above list, nor the highest offer received in any interval of time. The same “rules” (or lack thereof) apply in informal markets for used goods (e.g., Facebook marketplace, Craigslist, newspaper classified listings), building construction services, and many others. While theory has compared various formal processes to auctions, little is known about how well auctions perform relative to these informal, unstructured processes.

In “Relinquishing Riches: Auctions vs Informal Negotiations in Texas Oil and Gas Leasing,” we empirically investigate the differences in performance between formal and informal mechanisms in the US market for mineral leases. The owners of trillions of dollars of proven US oil and gas reserves must partner with exploration and production (E&P) companies in order to develop them, and these partnerships are codified in contracts called mineral leases. E&P companies typically know much more about the value of mineral resources than the owners of these reserves do, so the details of the transaction mechanism may have important effects on how economic surplus is created and shared between the two parties.

Extraction rights on roughly three quarters of US reserves are controlled by private landowners, who acquired them as part of their surface ownership. Private landowners generally allocate mineral leases through informal negotiations, often when they receive an unexpected knock on the door by an interested E&P company. The remaining quarter of US reserves are publicly controlled by state and federal agencies. In contrast to the private market, these public owners nearly always allocate mineral leases by conducting centralized and well-publicized auctions. In this paper, we ask if the quality of transactions in the market for private mineral leases would improve if sellers used auctions instead.

A natural experiment in Texas

We focus on Texas, where a natural experiment stemming from the state’s unique colonial history allows us to estimate the causal impact of using auctions to allocate mineral leases. After declaring independence from Mexico in the mid-19th century, the Republic of Texas appropriated millions of acres of unsettled land to a Permanent School Fund (PSF) to benefit public schools. When this land was initially sold to private citizens, Texas, following its Spanish colonial tradition, retained the rights to exploit minerals beneath the surface.

While this may initially have been a minor annoyance to land owners, it became a hotly contested issue in the early 20th century following the discovery of oil. To ward off armed rebellion by landowners who had purchased surface-only rights from the PSF, the Texas legislature passed the Relinquishment Act in 1919, which eventually gave private landowners who had previously purchased land out of the PSF the right to negotiate leases on the state’s behalf, in exchange for half of the proceeds. This negotiation arrangement persisted until 1973. After that point, all subsequent mineral leases on remaining PSF lands were allocated via auction. This temporal cutoff governs the manner in which minerals can be leased on nearly 8 million acres of land across Texas to this day.

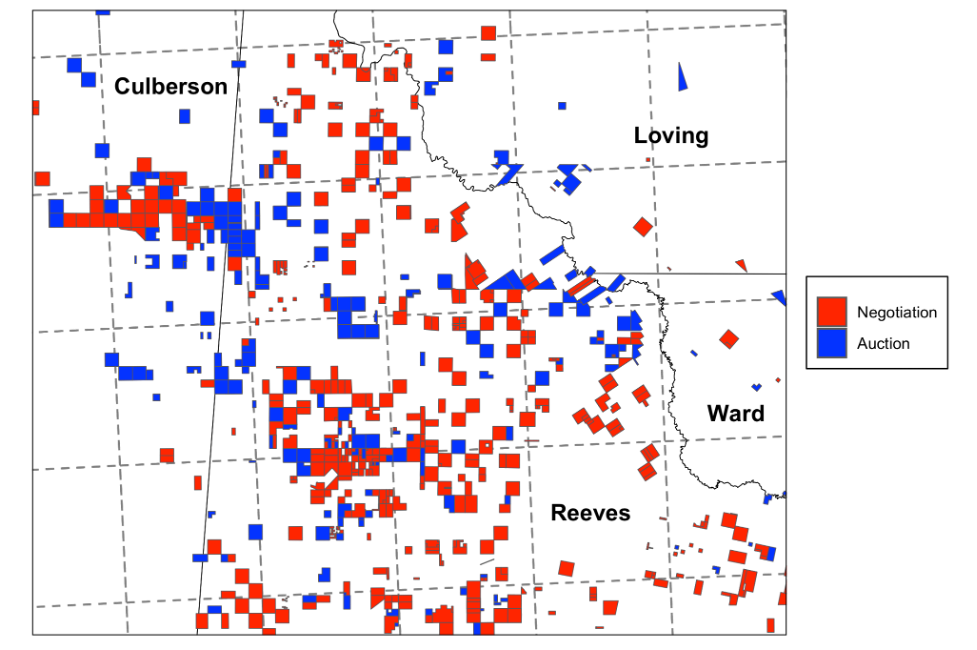

We leverage this history to study the impact of auctions during the recent shale boom at the turn of the century. The history above resulted in a checkerboard pattern of auctioned and negotiated leases sitting side-by-side throughout the State (Figure 1). Since this pattern was determined decades before the invention of shale technology, it is plausibly uncorrelated with other latent determinants of lease value, like mineral quality and present-day surface investments. This unusual situation allows us to compare otherwise equivalent negotiated leases and auctioned leases, something that would be impossible to do in other mineral leasing settings.

Figure 1: Example sample leases

Our primary sample contains 1,061 negotiated leases and 454 auctioned leases signed between 2004 and 2016. Since the state of Texas owns the minerals on all these leases, we observe detailed administratively recorded data on each of them, including the exact date signed, terms of the lease, and monthly production and revenue streams.

Auctions substantially increase payments to sellers

Mineral lease contracts have three key elements: a primary term indicating how much time the E&P company has to commence extraction; a royalty rate providing the landowner with a share of any realized drilling revenues; and an up-front bonus payment from the E&P company to the landowner to secure the right to explore. At auction, the primary term and royalty rate are held fixed, and bidders submit bonuses as bids. In principle, all three elements are negotiated in the private market. However, in the lands covered by our natural experiment, we see very little variation in royalty and term, compared to bonuses. Moreover, as most mineral leases do not result in drilling, up-front bonuses reflect the sole source of revenues most landowners end up receiving. For these reasons, we begin by comparing the bonuses paid to landowners in the two mechanisms.

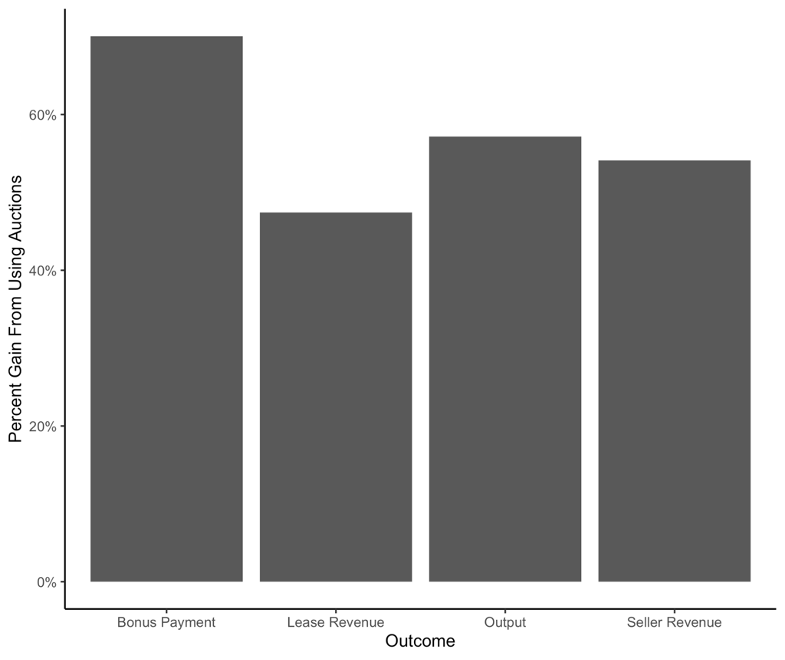

Our empirical strategy compares bonuses for leases signed at roughly the same time in roughly the same place. For example, we regress the log of bonus payments onto an indicator for being auctioned, and include fixed effects for each 100 square mile section of Texas and each year-quarter of our sample. Although we argue the leasing mechanism is as good as randomly assigned, these fixed effects ensure that comparisons are only made between auctioned and negotiated leases that share the same resource quality and economic environment. We find that auctioned leases sell for 70% more than similar negotiated leases (Figure 2). This result is robust to a wide range of controls and sample restrictions, and is not caused by differences in the likelihood that auction and negotiation parcels have a successful transaction. The economic significance of these differences is large: on average, negotiated leases would have generated $185,000 more upfront revenue had they been transacted using an auction.

Figure 2: Estimated gains from using auctions

Auctions also allocate assets more productively

The fact that auctions pay landowners more than negotiations is perhaps unsurprising. Faced with the threat of more competition, and being forced to make a single “best” offer, it makes sense to expect that E&P companies would bid more in an auction than they offer in a negotiation. Thus, part of the difference in bonus payments that we observe reflects a predictable transfer in surplus from buyers (E&P companies) to sellers (landowners).

However, it is not obvious whether auctions and negotiations would necessarily result in the same firm obtaining the lease. A well-designed auction always allocates an asset to the bidder who values it the most, while the informality of the negotiation process may result in the object being awarded before the highest value user has had a chance to counter, or perhaps even to bid at all. If firms that value the asset more are willing to pay more, and if auctions more reliably award assets to the highest value firm, then the higher bonus payments we observe in auctions could additionally be driven by an increase in the surplus created by the partnership, rather than just a transfer.

The market for mineral leases is an ideal environment to study how productively firms are using assets they acquire. The exact amount of oil and gas each lease produces is recorded in administrative data, and these undifferentiated products are sold in a global and highly competitive market. This means we can easily compute the economic value of production from a lease, and then use the same empirical strategy we employed to study bonuses to measure the effect of auctions on the productivity of mineral leases.

Our analysis shows that auctioned leases produce roughly 50% more output than negotiated leases. These results are again robust to a variety of temporal and spatial controls. Using the royalty rate for each lease, which is actually slightly higher for auctions, we compute the impact of this increased production on seller revenues. Combining discounted royalty payments and up-front bonuses, we estimate that auctions increase total payments to sellers by about $341,000 per lease, on average.

Discussion and implications

What’s driving these large payment and productivity gains from auctions? Conceptually, the gains from using a good mechanism will be largest when there is a lot of heterogeneity in potential buyer values. Thousands of E&P companies operate in Texas, which means that some of the largest companies in the world, like Exxon and Chevron, compete for leases against a multitude of privately held E&P companies with fewer than 20 employees. Within this group, there are wide differences in size and observable measures of sophistication. Thus, it is possible that some firms are persistently more productive than others, and so the gain to using a mechanism that always picks the most productive firm could be large.

There are also more idiosyncratic differences that lead some firms to be able to use particular parcels more productively than others. For example, some parcels may be in close proximity to other active leases that one firm owns and intends to drill soon, meaning they have equipment and crew in the area. Additionally, shale resources vary considerably across space, so past experience in one part of a shale play may lead otherwise similarly sophisticated E&P companies to have very different levels of productivity in a particular location. Finally, the volatile nature of global energy markets, coupled with the time-limited nature of lease terms, may result in some firms having much more organizational bandwidth at a given time than others. All of these idiosyncratic differences are hard for landowners to discern, but are exactly the type of private information that auctions are designed to extract.

There are two patterns in our data that suggest the large productivity gains from using auctions must reflect at least some improvement in the quality of matches between firms and leases. First, since the largest firms in our sample all participate in both auctions and negotiations, we can measure whether the same firm pays and produces more on the leases it wins at auction, compared to leases it wins at negotiation. When comparing productivity across leases within an individual firm, we find that both bonuses and output are larger at auction than through negotiation. This discrepancy would not appear if the difference in productivity between auctions and negotiations was driven by persistently “better” firms winning more often at auction.

Second, we take advantage of the fact that, for auctioned leases, we observe all bids made, as well as the identity of the firms who made each bid. If there are persistent productivity differences between firms A and B, then we ought to observe that A always bids more than B whenever the two firms bid for the same lease. Instead, we find that in situations where the largest firms in our data go head to head, it is effectively a coin toss which one bids higher on any individual occasion. These results lead us to conclude that the quality of a match between firms and leases, rather than simply the quality of the firm, is an important source of the productivity gains we measure.

Why do negotiations perform so poorly? Conceptually, our results require that auctions attract more (or “better”) bidders and/or that auctions select the highest value bidder more reliably than negotiations do. Although administrative records for the process leading up to a negotiation do not exist, which prevents us from documenting which bidders arrive at a negotiation and which one wins, we can use the detailed auction data to measure how costly losing a bidder, or picking the wrong one, would be in an auction. This data shows that the difference in bonus payments between auctioned and negotiated leases is comparable to both the cost of losing a bidder in an auction, and to the loss from picking the second or third best bidder instead of the first. These patterns support both the hypothesis that auctions bring in more competition than negotiations and the hypothesis that they “pick” better winners. Beyond these issues, we also know from survey data that mineral lease negotiations are not especially sophisticated in most cases; few sellers consult with an attorney, and many sellers accept the first offer they receive.

While it may be possible to help landowners negotiate better through education and legal representation, policy encouraging auctions in place of negotiations is likely to be less expensive and more effective. The costs associated with organizing an auction may have been large prior to the Internet era, but today there are electronic mineral auction platforms whose fees are 10% or less of the final transaction price. Given the magnitude of the difference between auctioned and negotiated payments, the gains that could be realized by encouraging this switch across the broader private leasing market—which is currently worth more than $3 trillion—would be enormous.

This article summarizes ‘Relinquishing Riches: Auctions versus Informal Negotiations in Texas Oil and Gas Leasing‘ by Thomas Covert and Richard Sweeney, published in The American Economic Review in March 2023. Thomas Covert is the Scientific Director of the University of Chicago Energy and Environment Lab. Richard Sweeney is an Associate Professor of Economics at Boston College.