Summary

In theory, market-based regulatory instruments—such as carbon pricing—have the potential to mitigate climate change at the lowest cost to society. However, rigorous empirical evidence on the efficacy of carbon pricing remains scarce. Our paper uses the experience of the European Union Emissions Trading Scheme (EU ETS) to start to fill that gap.

Introduced in 2005, the EU ETS established a price for the right to emit carbon dioxide by imposing a cap on the aggregate emissions for more than 12,000 power and manufacturing plants in 31 countries, covering 45% of EU emissions and 5% of global emissions. Using comprehensive administrative data from the French manufacturing sector, we estimate that the introduction of the EU ETS led to a 14% reduction in carbon emissions during Trading Phase I (2005-2007) and a 16.3% reduction in Trading Phase II (2008-2012)—equivalent to 5.4 million tons of carbon annually.

We find no evidence that the EU ETS led to a contraction in value added, employment, or investment among regulated firms. Instead, the lower level of emissions reflected an overall reduction in the emissions intensity of production.

For these emissions reductions to contribute to climate change mitigation it must be the case that they represent global reductions in emissions, not just a relocation of emissions to unregulated firms or markets. We investigate three potential channels for carbon leakage: the outsourcing of the more carbon intensive parts of a firm’s value chain, a shifting of production to unregulated firms, and the reallocating of production from regulated to unregulated facilities within the same firm. Our findings suggest that leakages through these channels were not sufficient to offset the reductions in emissions that we see at regulated plants.

The key mechanism behind the reduction in the emissions intensity of production appears to be capital investment in cleaner technologies. Our findings also suggest that the adoption of these more efficient technologies offset the higher input costs that resulted from carbon pricing. We formalize the intuition through a model in which firms face a choice: either reduce emissions through marginal cost increases, which leads to contractions in economic activity—the standard model—or invest in new technologies, which requires an upfront cost but lower marginal costs in the long run. Our extension to the standard model rationalizes our empirical findings, suggesting that when firms make such investments decarbonization may only be costly in the transition phase—due to switching costs that have no productive effect—rather than in the long term.

Our analysis shows that well-designed market-based climate policies that allow firms to respond flexibly can successfully reduce carbon emissions without imposing significant economic costs. However, investments in more efficient production processes appear important in mitigating costs in the long run. As governments worldwide consider strengthening carbon pricing programs, our study provides encouraging evidence that such market-based instruments can be both environmentally effective and economically viable.

Main article

Despite the high costs that greenhouse gas emissions impose on society through climate change, these externalities remain largely unpriced in economic decision-making. As governments worldwide consider strengthening carbon pricing programs, our study provides encouraging evidence that—where firms can respond flexibly and are able to make investments in more efficient production processes—such market-based instruments can be both environmentally effective and economically viable.

The unchecked accumulation of greenhouse gas emissions is one of the starkest examples of market failure worldwide. Despite the high costs they impose on society through climate change, these externalities remain largely unpriced in economic decision-making. In theory, market-based regulatory instruments—such as carbon pricing—have the potential to mitigate climate change at the lowest cost to society. By putting a price on carbon emissions, such policies create incentives for firms to abate pollution, invest in cleaner technologies, and make production processes less emissions intensive.

The unchecked accumulation of greenhouse gas emissions is one of the starkest examples of market failure worldwide.

Yet, rigorous empirical evidence on the efficacy of carbon pricing remains scarce. Does pricing emissions lead to their reduction, and if so, do these reductions translate into global emissions abatement? Or do firms simply shift production to unregulated markets, resulting in carbon leakage? In our paper (Colmer et al., 2024), we evaluate these questions by analyzing the consequences of the European Union Emissions Trading Scheme (EU ETS)—the world’s first and largest market-based climate policy.

Evaluating the EU ETS

Introduced in 2005, the EU ETS established a price for the right to emit carbon dioxide by imposing a cap on the aggregate emissions for more than 12,000 power and manufacturing plants in 31 countries, covering 45% of EU emissions and 5% of global emissions. Under the cap, firms receive or purchase emission allowances, which they can trade with one another. In principle, this system encourages cost-effective mitigation: firms with lower abatement costs can sell excess allowances, while firms facing higher abatement costs can purchase them instead of reducing emissions directly. However, the effectiveness of such a system depends on its regulatory stringency and firms’ responses. If permit prices are too low, firms may not be sufficiently incentivized to cut emissions. If firms outsource carbon-intensive production to unregulated firms or markets, global emissions may not decline.

Rigorous empirical evidence on the efficacy of carbon pricing remains scarce.

Reducing carbon without contractions in economic activity

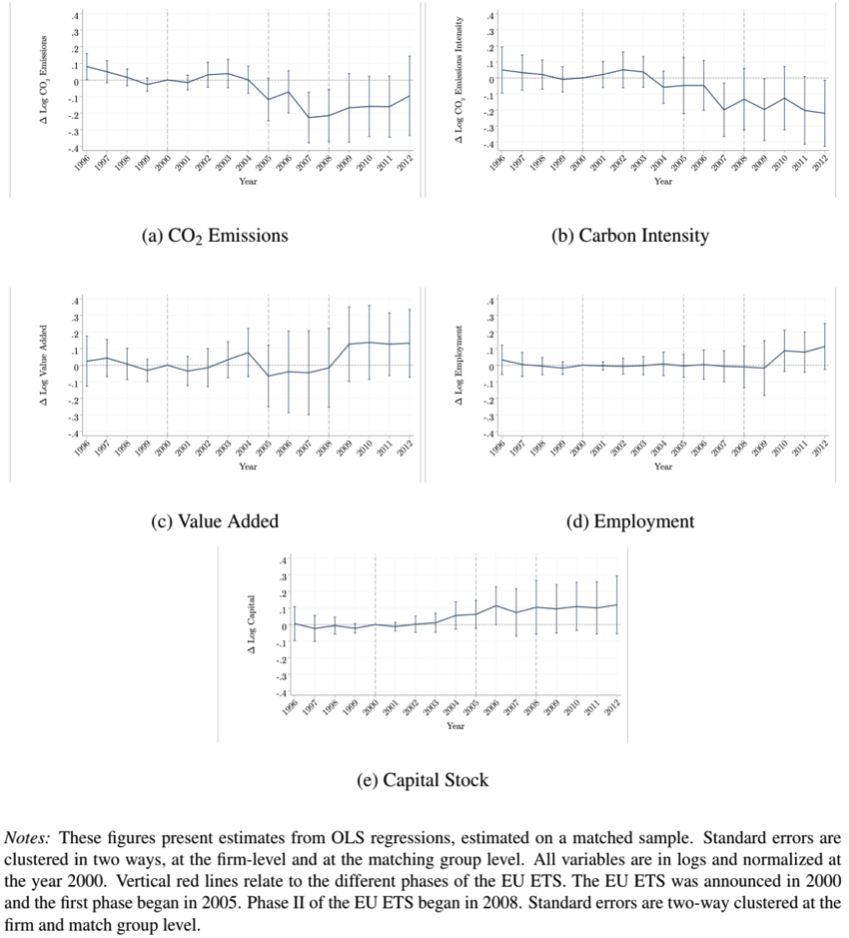

Using comprehensive administrative data from the French manufacturing sector, we estimate that the introduction of the EU ETS led to a 14% reduction in carbon emissions during Trading Phase I (2005-2007) and a 16.3% reduction in Trading Phase II (2008-2012)—equivalent to 5.4 million tons of carbon annually. These reductions account for 28-47% of the total reduction in industrial emissions in France over this period. We find no evidence that the EU ETS led to a contraction in value added, employment, or investment among regulated firms (Figure 1). This suggests that firms adapted rather than downsized. The combination of lower emissions and the absence of economic contractions meant that there was an overall reduction in the emissions intensity of production.

Figure 1. The EU ETS led to significant emissions reductions without contractions in economic activity

Source: Colmer et al (2024)

The EU ETS led to a 14% reduction in carbon emissions between 2005 and 2007, and a 16.3% reduction between 2008 and 2012.

Did carbon leakage undermine the EU ETS?

For these emissions reductions to contribute to climate change mitigation it must be the case that they represent global reductions in emissions, not just a relocation of emissions to unregulated firms or markets. We investigate three potential channels for carbon leakage.

First, firms could outsource the more carbon intensive parts of their value chain to unregulated firms or markets. Such a strategy could save on compliance costs, particularly if applied to the most carbon-intensive steps of the value chain, but it would inevitably reduce the firm’s value added. We do not find evidence of any such reduction. We also calculate a carbon-weighted measure of a firm’s imports value, which is sensitive to very carbon intensive imports. Using this measure, we find that increased imports could at most account for 10% of the estimated reduction in emissions during Trading Phase II. Overall, we find little evidence that outsourcing is likely to be a major driver of our estimated emissions reductions.

A second potential channel of carbon leakage is via the product market. Because carbon pricing increases production costs at regulated firms, market forces might shift production to unregulated firms within France or abroad. If this process was driving the reduction in emissions, we would also expect contractionary effects on value added, employment, or capital as firms face greater competitive pressures. However, we find no evidence that the ETS led to contractions in these measures, nor any change in the likelihood of firm survival.

We find no evidence that the EU ETS led to a contraction in value added, employment, or investment among regulated firms.

A third leakage channel could arise if firms operating multiple facilities reallocate production from regulated to unregulated ones. To account for this, we estimate the effects of the EU ETS at the firm level. This ensures that our results capture net emissions reductions, internalizing within-firm reallocations. Our findings suggest that any within-firm reallocations were not sufficient to offset the reductions in emissions by regulated plants.

How firms reduced emissions

The absence of evidence on carbon leakage, combined with the decrease in the carbon intensity of value added, suggest that the estimated reduction in emissions arose from improvements to the emissions intensity of production. Indeed, the key mechanism we identify is capital investment in cleaner technologies. Regulated firms significantly increased their investments in integrated production technologies that reduce air and climate-change-related pollution emissions. This interpretation is supported by data from interviews conducted in 2009 (Martin et al., 2014a,b), during which more than 30% of managers reported adoption of equipment to optimize the heating system, benefit from waste heat or improve the energy efficiency of industry-specific processes, machinery or lighting.

The key mechanism we identify for the reduction in the emissions intensity of production is capital investment in cleaner technologies.

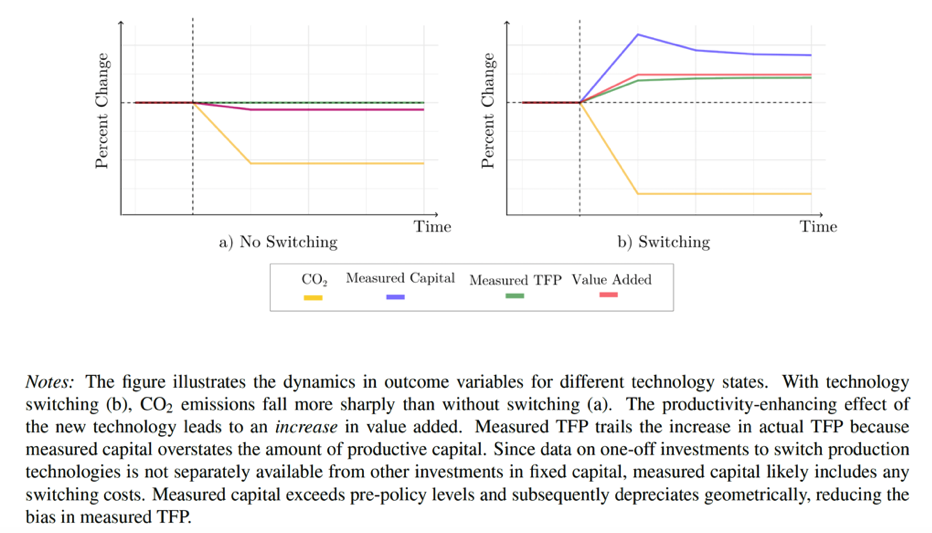

While carbon pricing increased input costs, our findings suggest that firms offset these costs by adopting the more efficient technologies.However, it was a priori unclear what conditions would be needed to rationalize such an interpretation. We formalize the intuition through a model in which firms face a choice: either reduce emissions through marginal cost increases, which leads to contractions in economic activity—the standard model—or invest in new technologies, which requires an upfront cost but lower marginal costs in the long run (Figure 2). Our extension to the standard model rationalizes our empirical findings, suggesting that when firms make such investments decarbonization may only be costly in the transition phase—due to switching costs that have no productive effect—rather than in the long term.

Figure 2: The Effect of Carbon Pricing with and without Technology Switching.

Source: Colmer et al (2024)

Our analysis shows that well-designed market-based climate policies can reduce carbon emissions without imposing significant economic costs.

Conclusion

Our analysis shows that well-designed, market-based climate policies can successfully reduce carbon emissions without imposing significant economic costs, by allowing firms to respond flexibly. However, investments in more efficient production processes appear important in mitigating costs in the long run. As governments worldwide consider strengthening carbon pricing programs, our study provides encouraging evidence that such policies can be both environmentally effective and economically viable. The EU ETS experience suggests that market-based instruments can play an important role in global climate change mitigation efforts.

This article summarizes ‘Does Pricing Carbon Mitigate Climate Change? Firm-Level Evidence from the European Union Emissions Trading System’ by Jonathan Colmer, Ralf Martin, Mirabelle Muûls, and Ulrich J. Wagner, published in The Review of Economic Studies in May 2024.

Jonathan Colmer is at the University of Virginia. Ralf Martin is at the International Finance Corporation (IFC) and Imperial College, London. Mirabelle Muûls is at the National Bank of Belgium and Imperial College, London. Ulrich J. Wagner is at the University of Mannheim.

References

Colmer, J., Martin, R., Muûls, M., Wagner, U. J. (2024) “Does Pricing Carbon Mitigate Climate Change? Firm-Level Evidence from the European Union Emissions Trading System”, Review of Economic Studies

Martin, R., M. Muûls, L.B. de Preux, and U.J. Wagner (2014a). On the Empirical Content of

Carbon Leakage Criteria in the EU Emissions Trading Scheme. Ecological Economics, 105:78-88

Martin, R., Muûls, M., De Preux, L., et al. (2014b), “Industry Compensation Under Relocation Risk: A Firm-Level Analysis of the EU Emissions Trading Scheme”, American Economic Review, 104, 1–24.