Summary

Kidney failure is a leading cause of death around the world. The best treatment is transplantation, but no country is presently able to supply all the transplants required by its patient population; most people with kidney failure will die without receiving a transplant. Kidneys have to be compatible with the recipient, so not everyone healthy enough to donate a kidney can donate one to whom they wish. Kidney exchange (KE) is a way to increase the number of transplants by allowing incompatible patient-donor pairs to exchange kidneys; each patient therefore receives a compatible kidney without violating the ban on paying donors. The first kidney exchanges involved just two patient-donor pairs, but the question soon arose as to how to coordinate these, on a large scale, in ways that would make it feasible to do exchanges among many—and possibly geographically distant—patients and donors.

One important barrier to larger-scale exchanges was that initially all surgeries were performed simultaneously, in order to prevent a broken link whereby some pair gave a kidney but did not get one. However, as evidence accumulated that living donation by unrelated donors was successful, donations started to be accepted more frequently from non-directed donors, who didn’t have a particular recipient in mind. These donors could facilitate more than a single transplant, by offering a kidney to the patient in a hard-to-match pair, whose donor could pass it forward to the patient in another such pair, whose donor could then donate to an individual on the waiting list for a deceased donor. In addition, chains begun by non-directed donors could be organized non-simultaneously, so that each patient-donor pair received a kidney before donating one of their own. The industry continues to innovate in ways that should enable more and longer kidney exchange chains. Today, for example, kidney exchange donors no longer have to be geographically close as kidneys can be flown between cities. There have also been innovations in financial engineering, which make it easier for hospitals with different cost structures to exchange with one another, Barriers between kidney exchange programs remain, however. In the U.S., for example, decentralization means that many transplant centers operate below efficient scale, and can only conduct exchanges among easy-to-match patient-donor pairs. Even if they enrol their hard-to-match pairs in one of the inter-hospital exchanges, the fact that easy-to-match pairs are being matched to each other makes it harder to find matches for hard-to-match pairs. Collaborations between EU countries are facing similar challenges. One step now being actively explored is breaking down the barriers between such programs in order to form larger pools of patient-donor pairs that can be searched to find matches for hard-to-match pairs. These efforts face considerable challenges, but the potential rewards are large; enabling transplants involving hard-to-match pairs across programs or borders would save both lives and years of costly dialysis. Early cross-border exchanges encountered some controversy, however, with some commentators claiming they should be regarded as organ trafficking; careful market design will therefore be vitally important.

Main article

No country is presently able to supply all the kidney transplants required by its population, and most people with kidney failure will die without receiving a transplant. Kidney exchange is a way to increase the number of transplants by allowing incompatible patient-donor pairs to exchange kidneys. For logistical reasons, early exchanges involved just two patient-donor pairs, but the rise in donors without a particular recipient in mind has enabled long chains of non-simultaneous transplants. However, barriers between kidney exchange programs, both within and across countries, continue to make it difficult to find matches for some patient-donor pairs. Breaking down these barriers will be challenging, but the potential rewards are large—both in terms of lives saved and reduced healthcare costs.

Kidney failure is a leading cause of death around the world. The best treatment is transplantation, but no country is presently able to supply all the transplants required by its patient population. In the U.S. and many other countries, most transplants today come from deceased donors. Another source of kidneys for transplantation is from healthy living donors, who can safely give one of their kidneys to save someone with kidney failure. However, there are almost 100,000 people on the waiting list for a deceased donor kidney in the U.S. at the moment, and about half a million on dialysis. We only manage about 17,000 transplants from deceased donors each year, with another 6,000 or so from living donors. Transplants are therefore in desperately short supply, and most people with kidney failure will die without receiving a transplant.

Most people with kidney failure will die without receiving a transplant; new research suggests breaking down boundaries between exchange programs may help

Note that it is against the law, in the U.S, and almost everywhere else, to pay a living donor to donate a kidney. The single exception is the Islamic Republic of Iran, where there is a legal monetary market for kidneys, although there are also black markets elsewhere around the world. There is a considerable literature on the desirability or undesirability of allowing donors to be compensated, that we will not discuss here, but see Roth (2021) for a discussion of compensation controversies in a number of markets.)

Kidneys have to be compatible with the recipient, so not everyone healthy enough to donate a kidney can donate one to whom they wish. Kidney exchange (KE) is a way to increase the number of transplants by allowing incompatible patient-donor pairs to exchange kidneys, so each patient receives a compatible kidney from another patient’s donor, without violating the ban on paying donors. KE is also called kidney paired donation (KPD), which avoids the use of the word “exchange.”

The development—and benefits—of kidney exchange chains

The simplest kidney exchange involves just two patient-donor pairs, with each patient receiving a kidney from the other patient’s donor. A handful of early exchanges were identified by hand, and conducted within individual transplant centers; the question arose as to how to coordinate these on a large scale, and in ways that would make it feasible to do exchanges among many patients and donors, who might often be at different hospitals.

A new paper charts the rise of non-simultaneous kidney exchange chains, and looks at the benefits to patients

This effort began slowly, and required constant adaptation of the market design in ways that engaged economists, computer scientists, and operations researchers in support of transplant professionals. Today, kidney exchange has become a standard form of transplantation in the United States and a few other countries, in part because of continued attention to operational details. However, much more remains to be done; the full potential of kidney exchange has yet to be realized, and there are still many more patients in need of transplants than can presently be saved.

An initial proposal for interhospital kidney exchange (Roth et al. 2004) considered exchanges in potentially long cycles and chains. These were not initially feasible logistically. Instead, early exchanges were between two patient-donor pairs at a time, with all surgeries performed simultaneously, to prevent a broken link causing some pair to give a kidney but not get one (and to no longer have a kidney with which to participate in a future exchange). Even this basic exchange therefore required four surgical teams and operating rooms, for the two nephrectomies (kidney removals) and two transplants. With experience, exchanges in a cycle among three pairs became feasible, which involved six simultaneous surgical teams and operating rooms.

As evidence accumulated that living donation by unrelated donors was successful, donations started to be accepted more frequently from non-directed donors, who wished to donate a kidney for purely altruistic reasons, and didn’t have a particular recipient in mind. After passing careful psychological and medical screening, such donors were allowed to donate to someone who had been waiting a long time to receive a deceased-donor kidney. However, the growing pool of kidney exchange pairs also offered a possibility that a non-directed donor could facilitate more than a single transplant, by offering a kidney to the patient in a hard-to-match pair, whose donor could pass it forward to the patient in another such pair, whose donor could then donate to an individual on the waiting list for a deceased donor. That would be another way to achieve three transplants via six surgeries, and we started to see chains of this sort.

Decentralization amongst U.S. kidney exchanges means that many transplant centers operate below an efficient scale

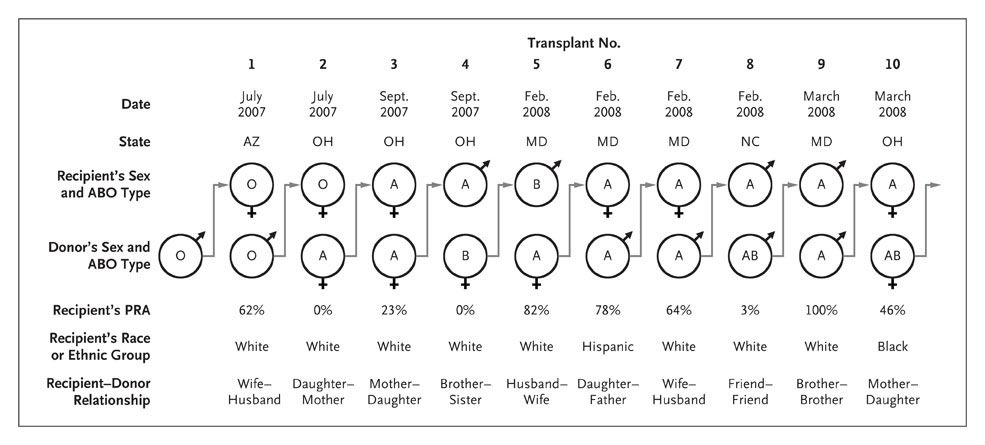

It was soon suggested that chains begun by nondirected donors could be organized non-simultaneously, so that each patient-donor pair received a kidney before donating one of their own (Roth et al. 2006). This non-simultaneity would both reduce the harm done if a link in the chain was broken, and simplify the coordination of operating rooms and surgical teams, which would allow more transplants to be accomplished, in longer chains. The idea remained controversial even after the first non-simultaneous chain was reported by Rees et al. (2009), which at the time contained ten transplants, conducted over seven months (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. The First NEAD Chain (Rees et al. 2009)

Source: Rees et al. (2009)

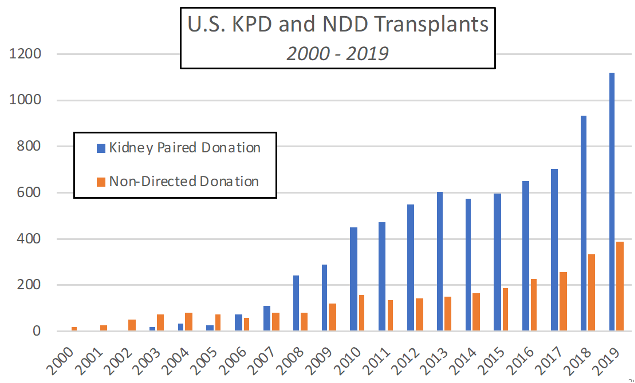

Over time, operational capabilities developed for quickly identifying and conducting chains, and evidence of the viability of this approach accumulated (Ashlagi et al. 2011a,b). As a result, non-simultaneous kidney exchange chains—and the non-directed donors who begin them—have become increasingly important in American kidney exchange, which has itself become a standard part of American transplantation (Figure 2).

Figure 2. U.S. KPD and NDD transplants 2000 – 2019

Optimization software typically puts weights on potential transplants (e.g., giving extra weight for a transplant to a child, or for one likely to add many additional life years) and finds maximum weight combinations of cycles (of limited length) and chains (of potentially unlimited length). These optimizations are computationally complex in theory, and computationally time-consuming instances do sometimes arise in practice. However, powerful optimizing software—together with various heuristics—has been developed that is capable of performing these tasks (Anderson et al. 2015)

The reason chains are important is that some patients are hard to match; there is only a small probability that any given kidney will be compatible with them. Patient-donor pairs with hard-to-match patients are therefore unlikely to be able to participate in pairwise exchange with another hard-to-match pair. However, if the pool of patient-donor pairs is large enough, even a hard-to-match patient may find some compatible donor in the pool, while his or her donor can match to another patient, whose donor can match to another. In this way, a non-directed donor might be able to initiate a long chain of possible transplants. Thus in a sufficiently large pool of pairs, the computational and logistical ability to assemble long chains can substantially reduce the constraint that non-monetary barter exchange can only be carried out among pairs for whom there is a “double coincidence of wants,” in Jevons’ famous phrase.

Kidney exchanges in the U.S. and globally

In the U.S., there are three active inter-hospital kidney exchanges: the National Kidney Registry (NKR, a private company despite its name); the Alliance for Paired Kidney Donation (AKPD); and a pilot program run by the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS), the federal contractor that supervises the deceased donor waiting lists. Together, these three exchanges perform almost half of the U.S. kidney exchange transplants, with the rest being performed internally by transplant centers, among their own patient-donor pairs.

Breaking down the barriers between kidney exchange programs – both within and across countries – could save lives and lower healthcare costs

This decentralization comes with both costs and benefits. A significant cost is that many transplant centers operate below efficient scale, and can only conduct exchanges among easy-to-match patient-donor pairs, because they don’t have a big enough pool of pairs to find compatible kidneys for their hard-to-match patients. Even if they enrol their hard-to-match pairs in one of the inter-hospital exchanges, the fact that easy-to-match pairs are being matched to each other makes it harder to find matches for hard-to-match pairs (Agarwal et al. 2019). To overcome this free-riding behavior, point-based mechanisms are being explored that reward hospitals based on the types of pairs they enroll in the pool (Agarwal et al. 2019). Collaboration attempts between EU countries that seek to collaborate with one another on kidney exchange are facing similar challenges (Biro et al. 2019).

Overall, however, decentralized kidney exchange has prompted innovation, as new ways to organize kidney exchange have been developed. Fifteen years ago, kidney exchange donors had their nephrectomies performed at the hospital where the recipient of their kidney would be transplanted, so pairs involved in exchange mostly had to be geographically close. Today, however, kidneys in inter-hospital exchanges are removed in one city and flown to another, so that chains can span the country.

There have also been innovations in financial engineering. These innovations both make it easier for hospitals with different cost structures to exchange with one another, and make it easier to cover the costs to donors and transplant centers that standard U.S. medical insurance may miss. These costs include lost wages for donors, and the costs to transplant centers of working up potential donors, who may ultimately not qualify to make a donation for as-yet-unknown recipients .

Kidney exchange is growing around the world. The first kidney exchange was in South Korea in the 1990s, but there are now effective national programs in Canada, the U.K. and the Netherlands, and smaller programs in many European countries (Biro et al. 2019). These programs are smaller in scale than exchange in the U.S., and most impose limits on nondirected donors and chains that preclude long chains. As in the U.S., these programs often involve interdisciplinary market design teams that focus on both medical logistics and algorithms. It is worth noting that kidney exchange is essentially illegal in Germany, where the current law stipulates that—with very few exceptions—a person can receive a living kidney donation only directly from an immediate family member. This law doesn’t appear to receive much public support (see Roth and Wang 2020), and revisions are often discussed, but so far without progress.

Breaking down barriers between programs could save lives and reduce healthcare costs

Essentially all of these kidney exchange programs are faced with some patients for whom a compatible kidney can be found only with great difficulty, if at all. (Patients who have had a previous transplant are often in this category.) One step now being actively explored is breaking down the barriers between programs in order to form larger pools of patient-donor pairs that can be searched to find matches for hard-to-match pairs. These efforts face considerable barriers, and are presently very-early-stage works in progress. One hopeful sign, however, is that financial barriers should not be an obstacle; the overall savings to healthcare when a hard-to-match patient receives a transplant are considerable.

The reason that kidney transplants are so cost effective is that the cost of a transplant is roughly the same as the cost of a year of dialysis—and a year of dialysis for a hard-to-match patient is followed by more years of dialysis, often ending in premature death. After receiving a successful transplant, however, a patient is not only restored to good health, but becomes much less expensive to maintain as immunosuppressive drugs are significantly cheaper than dialysis. A transplant can therefore save not only lives, but also years of costly dialysis, which produces financial savings that can be used to fund extra costs associated with, for example, exchanging kidneys across national borders.

One additional non-directed kidney donor can enable multiple kidney transplants, including for hard-to-match patients

The financial savings of a transplant creates the possibility of opening up international kidney exchange globally. Exchanges need not be just between rich countries with many hard-to-match patients enrolled in kidney exchange programs. Exchanges could also be between wealthy countries with many patients on dialysis, and middle income countries with the ability to care for transplant patients, but without the financial structure to make transplants widely available. Pilot exchanges of this kind between the U.S. and other countries have shown its feasibility (Rees et al. 2017). These cross-border exchanges encountered some controversy, however, with some commentators claiming that they should be regarded as organ trafficking—though national surgical associations and medical ethicists have now debunked those claims. In general, the design of kidney exchange has to be sensitive to the considerable repugnance associated with the existence of illegal black markets for kidney transplants, run by criminals, which can exploit vulnerable people and can provide inadequate care for both donors and patients. This makes careful market design all the more important as we seek to expand the scope of life-saving kidney transplantation (cf. Nikzad et al. 2021).

This article summarizes ‘Kidney Exchange: An Operations Perspective’ by Itai Ashlagi and Alvin E. Roth, published online in Management Science in July 2021.

Itai Ashlagi is at the Management Science and Engineering Department at Stanford University. Alvin E. Roth is at the Department of Economics at Stanford University.