Summary

What roles do moral values play in elections, and how do politicians appeal to them? To examine these questions, this research introduces a core idea of modern moral psychology into the study of political economy. People may endorse “universalist” values, such as individual rights, justice, and impartial fairness, or more “communal” concepts, such as community, loyalty, betrayal, respect, and tradition.

This may help in understanding election outcomes. The research summarized here asks whether voting decisions in the United States partly reflect the match between the moral values of voters and politicians. It introduces methods for studying the moral types of politicians and voters, and the extent to which people vote for candidates or parties that appeal to their own values.

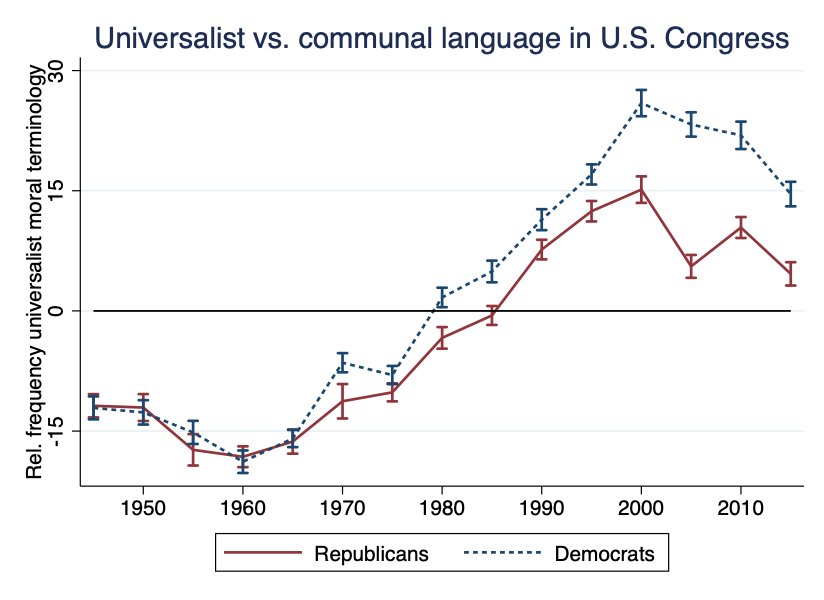

The moral types of politicians and voters are not observed directly, but can be inferred using psychological questionnaires for voters, and text analyses for politicians. These reveal the relative importance placed on universalist versus communal morality. Text analyses of speeches in the U.S. Congress show that, from the 1960s onwards, Republicans and Democrats polarized in their moral appeal. For more than thirty years, Democrats placed increasing emphasis on universalist moral concepts, a trend that was weaker among Republicans.

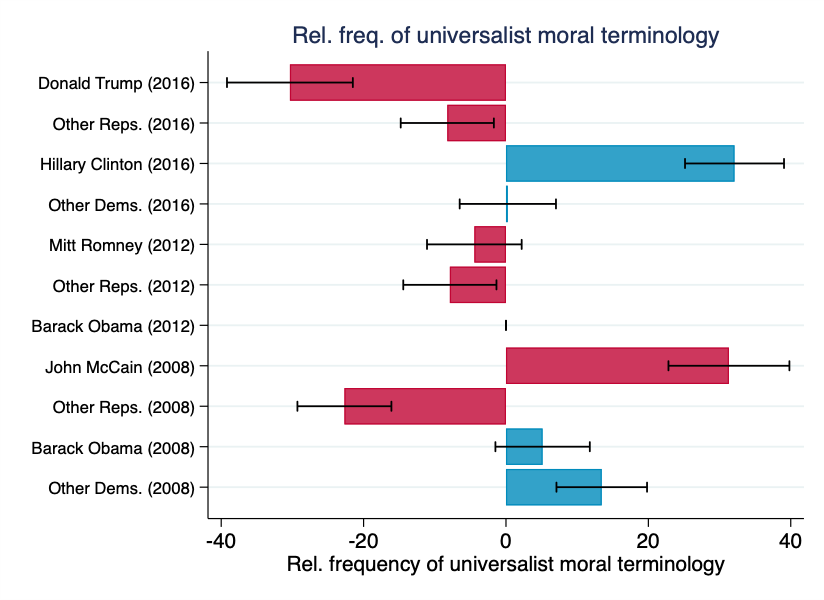

This approach can also be applied to the campaign speeches and statements of presidential candidates. The moral appeal of politicians varies across parties, but also within them. Donald Trump’s moral language was more communal than his rivals in the primaries, and more than any other presidential nominee in recent history. Voters with relatively communal values are more likely to vote Republican, helping to explain the election outcome in 2016.

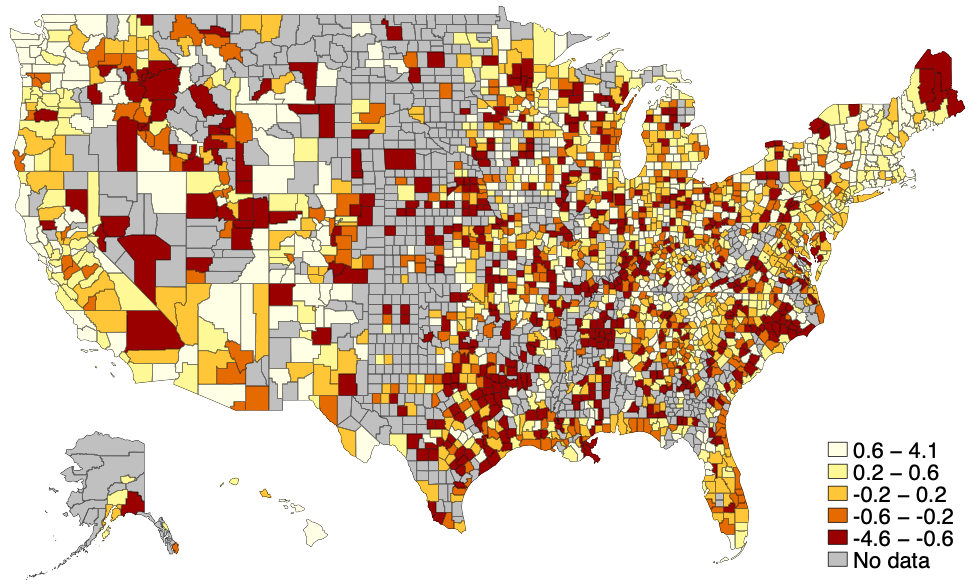

The research also draws on survey responses, partly to study geographic variation. Large parts of the coastal areas appear highly universalist, but there is wide variation even within narrowly-defined regions, and strong moral polarization between rural and metropolitan areas. The relative importance of universalist values has declined over time. This is consistent with the text analysis of Congressional speeches, in which universalism declined from the late 1990s onwards.

Putting the pieces together to study the 2016 Presidential election, moral universalism is correlated with voting Democratic. Holding fixed the voting decision in 2012, Clinton voters emphasized universalist moral values more than Trump voters; those who “switched” from Obama to Trump mainly endorsed communal values. Looking at within-party variation, people who voted for Trump in the primaries had more communal values than those voting for another GOP candidate. Looking at the 2012 and 2016 Republican primaries, communal versus universalist values also help to explain the pattern of votes across counties.

Further analysis indicates that these findings are not due to varying economic motivations. Instead, moral universalism is a separate – and in economics largely unexplored – influence on political outcomes. The research shows how new forms of data help to interpret recent election results. Examining politician and voter moral frameworks through the lens of universalism promises to deepen our understanding of politics, and the sources of polarization along partisan lines.

Main article

This research studies the supply of, and demand for, moral values in recent U.S. presidential elections. A combination of large-scale survey data and text analyses supports the hypothesis that voters and politicians vary in their emphasis on universalist relative to communal moral values. Politicians’ vote shares partly reflect the extent to which their moral appeal matches the values of the electorate. Over the last decade, the values of Americans have become increasingly communal – especially in rural areas – which led to increased moral polarization and is associated with changes in voting patterns across space.

What roles do moral values play in election outcomes? What are the key moral frameworks that voters maintain? How do politicians appeal to these different moral frameworks? This article summarizes a recent research paper which examines these questions, by introducing a core aspect of modern moral psychology into the study of political economy.

Universalist versus communal moral values

Recently, the psychologist Jonathan Haidt and his collaborators popularized an influential positive framework of morality, concerning people’s beliefs about what is “right” and “wrong.” This framework, known as Moral Foundations Theory, is centered on the basic empirical fact that individuals vary widely in the types of values they emphasize.

On the one hand, people assign moral relevance to concepts that pervade normative analyses of morality, including individual rights, justice, impartial fairness, and avoidance of externalities. Such ”universalist” values have the key characteristic that they apply irrespective of the context or identity of the people involved.

On the other hand, people also assign moral meaning to ”communal” or ”particularist” concepts, such as community, loyalty, betrayal, respect, and tradition. These values differ from universalist ones in that they are tied to certain relationships or groups. For example, one core trade-off that characterizes these values is that between an ethic of universal human concern versus loyalty to the local community. The basic distinction between a universalist and a particularist morality has been at the center of philosophical debates for decades and is the subject of much psychological and evolutionary research.

There are good reasons to believe that differences in moral values may help in understanding the outcomes of elections. Political theorists such as Michael Sandel have long argued that past U.S. presidential nominees have lost elections because they failed to appeal to voters’ communal moral values. In addition, a rich body of sociological work forcefully argues that many, particularly those forming the white rural working class, are deeply concerned about a “moral decline,” in particular as it relates to the loyalties and interpersonal obligations that characterize the social fabric of many local communities. Furthermore, psychologists have shown that communal values tend to be more prevalent among conservatives.

The research summarized here studies the hypothesis that voting decisions partly reflect the match between voters’ and politicians’ moral values. To this effect, I propose a method for jointly studying the moral types of politicians, the values of individuals, and the extent to which individuals vote for candidates or political parties that appeal to their own moral values.

To test this idea, we require empirical measures of the preferred moral frameworks of politicians and voters. Since politician and voter moral types are latent (not observed directly), I infer them using a combination of psychological questionnaires for voters and text analyses for politicians. Both the questionnaire and the text analyses aim at deriving a simple one-dimensional summary measure: the relative importance that a voter or politician places on a universalist vs. communal morality. To clarify, this research is not about who is “more moral”, but about the specific types of moral reasoning that people cherish and endorse.

Estimating politician moral types

To determine politician moral types, I conduct text analyses that are based on a psychological dictionary of universalist and communal keywords. To classify the ”average” Republican and Democrat, I study moral rhetoric in speeches given in the U.S. Congress between 1945 and 2016. Figure 1 documents that, starting in the 1960s, Republicans and Democrats polarized in their moral appeal: for more than thirty years, Democrats placed increasing emphasis on universalist moral concepts, a trend that was weaker among Republicans. Thus, today, the Democratic party has a substantially more universalist profile than the Republican party.

Figure 1: Universalist vs. communal language in U.S. Congress

These cross-party differences set the stage for an analysis of the campaign documents (speeches, statements, debates, etc.) of individual presidential candidates. The results, shown in Figure 2, suggest that the moral emphasis of politicians varies widely across and – perhaps more surprisingly – also within parties. In 2016, Donald Trump’s moral language was the least universalist (or equivalently, most communal) of any presidential nominee in recent history. Trump was also far more communal than his 2016 primary rivals. The difference in moral emphasis between Trump and Hillary Clinton was especially pronounced, relative to earlier candidate pairs.

A helpful way to think about the text analyses is that they deliver predictions on how voters’ moral values will influence their votes. For example, based on the text analysis, we expect that communal voters will vote Republican, and that they were more likely to vote Republican in 2016 than in earlier elections, given the marked divergence in moral emphasis between Trump and Clinton. Furthermore, given that Trump was also the most communal candidate in the set of 2016 GOP contenders, we should also expect communal values to be predictive of voting for Trump in the Republican primaries. The text analysis makes many analogous predictions for the other presidential candidates.

Figure 2: Relative frequency of universalist moral terminology

Geographical and time series variation in moral values

Part of the analysis of voters that is summarized here rests on a large-scale online survey dataset. Since 2008, almost 280,000 U.S. residents have completed the so-called Moral Foundations Questionnaire on the website www.yourmorals.org. This questionnaire allows the calculation of a summary measure of respondents’ universalist vs. communal moral values that corresponds closely to the text analyses described above. Notably, while the respondents are not representative of a county’s population, the large sample size allows a meaningful county-level index of moral values to be computed.

Figure 3 depicts the county-level variation in moral universalism, where lighter yellow colors indicate higher emphasis on universalist values and darker red colors higher emphasis on communal values. There are two takeaways. First, the relative emphasis that people place on universalist moral principles varies in intuitive ways across U.S. regions. For instance, large parts of the coastal areas appear highly universalist. Second, and perhaps more interestingly, the map also reveals wide variation in moral frameworks within relatively narrow geographic regions such as states, or even commuting zones. Indeed, much of the analysis in the original research paper (Enke 2020) relies on leveraging this fine-grained variation in morality across counties within the same commuting zone.

Figure 3: Relative importance of universalist vs. communal moral values

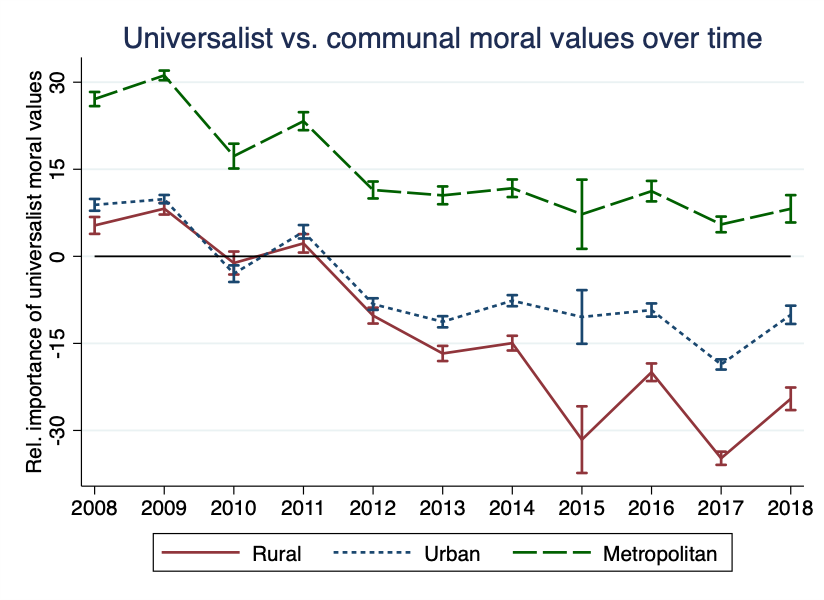

Figure 4 illustrates the variation in moral frameworks in a different way, showing how average moral universalism has evolved over time since 2008, separately for rural, urban, and metropolitan areas. We see that the relative importance placed on universalist values decreased over the time span considered here, which is notably consistent with the text analysis of Congressional speeches, in which universalism also declined since the late 1990s. In addition, we observe strong moral polarization between rural and metropolitan areas: while metropolitan areas are always more universalist, the difference increased significantly in recent years.

Figure 4: Universalist vs. communal moral values over time

Linking voter values, politician moral types, and voting

Having established heterogeneity in moral reasoning among politicians and voters, we are ready to put the pieces together: who do universalists and communalists vote for, and how does this line up with the predictions made by the text analysis?

Figure 5 illustrates the results for the 2016 Presidential election. The left panel shows the average moral universalism index for groups of people that exhibit a given voting pattern. For example, the two rightmost bars show average moral values among people who voted for Mitt Romney in 2012, partitioned by whether they voted for Trump or Clinton in 2016. Likewise, the two leftmost bars focus on the voters who voted for Obama in 2012, again partitioned by whether they voted for Trump or Clinton in 2016. Similarly, the right panel shows average moral universalism among groups of voters according to their voting behavior in the 2016 Republican primaries.

This figure highlights three main points, all of which line up with the predictions made by the text analyses. First, moral universalism is correlated with voting Democratic. Second, holding fixed the voting decision in 2012, people who voted for Clinton emphasize universalist moral values more strongly, and people who voted for Trump emphasize communal moral values more strongly. This result aligns with the text analysis because (i) Trump is more communal in 2016 than Romney in 2012 and (ii) Clinton is more universalist in 2016 than Obama in 2012. In other words, those people who “switched” from Obama to Trump predominantly cherish communal values. Third, focusing on within-party variation, we see that people who voted for Trump in the primaries are more communal than those who voted for one of the other GOP candidates. Again, this lines up with the text analysis.

An important question is whether voter moral values are just a proxy for the economic motivations that economists studying politics typically emphasize. This could be the case if, for example, moral values were strongly correlated with income or wealth. However, this is not the case. First, moral universalism is largely uncorrelated with traditional economic variables. Second, econometric analyses show that the strong relationship between voting and moral values in the 2016 election (both the general election and the primaries) also holds when controlling for a range of economic and demographic covariates, such as income, education, religiosity, age, and gender. This suggests that moral universalism is a separate – and hitherto in economics largely unexplored – characteristic that governs political decision-making.

Figure 5: Moral values by voter type

Ultimately, the methods developed in this research are not (just) designed to understand the result of the 2016 general election, but instead the role of morality in U.S. elections more generally. Therefore, we proceed by directly matching the predictions of the text analysis with the behavior of voters. Specifically, it should be that relatively universalist voters (or relatively universalist counties) generally vote for those candidates that appear more universalist in the text analyses. If a candidate in a given race is relatively more universalist in their moral language than their direct competitors, that candidate’s county-level vote share should be more positively correlated with the county-level moral universalism index.

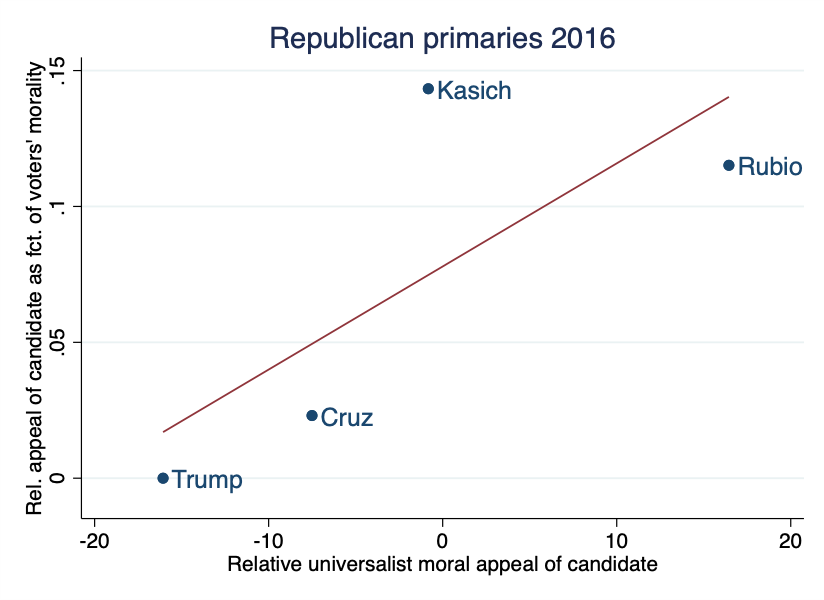

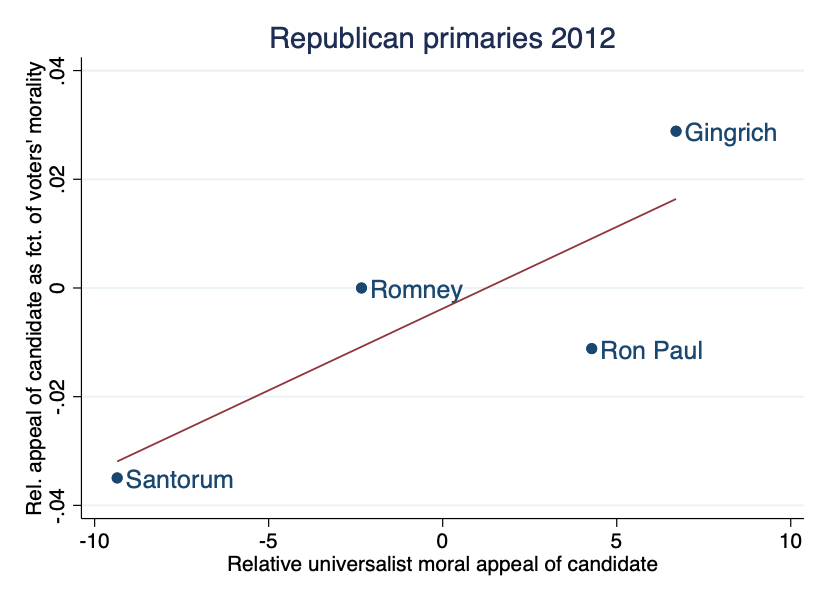

Figure 6 illustrates this analysis by focusing on the 2016 and 2012 Republican primaries. By construction, these analyses only leverage within-party variation in voting. This is arguably a strong test of the idea that moral universalism matters for election outcomes because – as documented above – much of the variation in moral frameworks is across parties, on the side of both politicians and voters.

We see that, in the Republican primaries in 2016, Ted Cruz was less universalist than Marco Rubio and John Kasich, and his county-level vote share was indeed less correlated with moral universalism. In 2012, Rick Santorum used highly communal language, and his vote share was negatively correlated with universalist values; opposite patterns hold for Newt Gingrich. Overall, the figures illustrate that the framework proposed in this research helpfully organizes the results of elections more generally, not just in 2016.

Figure 6: Relative universalist moral appeal of candidate

What we have learned

Voters vary widely in the extent to which they cherish universalist or communal moral principles. The research summarized here shows how this helps in understanding recent election results. Just like voters, politicians strongly differ in the moral values that they appeal to and endorse. As a result, universalist voters vote for universalist politicians, and communal voters for communal politicians. Examining politician and voter moral frameworks through the lens of universalism promises to deepen our understanding of political processes and polarization along partisan lines. For instance, the recent rise of affective polarization – people disliking supporters of the opposite party – could partly be driven by heterogeneity in moral reasoning. After all, some of the hostility in political conflict may stem from people having a hard time understanding that those on the other side of the aisle are not selfish, but act on different moral priorities.

This article summarizes “Moral Values and Voting”, by Benjamin Enke, published in the Journal of Political Economy in October 2020.