Summary

Which has more impact on our wealth and behavior: biology or environment? This research attempts to disentangle the role of nature versus nurture and the role of nature-nurture interactions in the intergenerational transmission of wealth. Results suggest that persistence in wealth across generations is primarily driven by environment, while biology has more impact on educational achievement.

Wealth is highly correlated between parents and their children; however, little is known about what drives this relationship. Is it that children of wealthy parents are inherently more talented, and that is what shapes their later success? Or is it that children had parents who gave them more opportunities because they themselves had more wealth? Using Swedish administrative data on children who were adopted, this research investigates this question by comparing the relationship between wealth of adopted and biological parents to that of the adopted child. The authors find that, even prior to any inheritance, there is a substantial role for environment and a much smaller role for biological factors. The authors find little evidence that nature-nurture interactions are important. They also compare these findings to those for other outcomes and find that while nature is relatively more important for education, environmental influences are relatively more important for wealth-related variables such as savings and investment decisions.

Main article

Wealth is highly correlated between parents and their children; however, little is known about what drives this relationship. Is it that children of wealthy parents are inherently more talented, and that is what shapes their later success? Or is it that children had parents who gave them more opportunities because they themselves had more wealth? Using Swedish administrative data on children who were adopted, this research investigates this question by comparing the relationship between wealth of adopted and biological parents to that of the adopted child. The authors find that, even prior to any inheritance, there is a substantial role for environment and a much smaller role for biological factors. The authors find little evidence that nature-nurture interactions are important. They also compare these findings to those for other outcomes and find that while nature is relatively more important for education, environmental influences are relatively more important for wealth-related variables such as savings and investment decisions.

Wealth inequality has increased dramatically in recent decades. This fact, in conjunction with the release of Thomas Piketty’s Capital in the 21st Century about the intergenerational transmission of wealth as a key determinant of the nature of society, has brought renewed interest in understanding how wealth transmission affects generational outcomes (Piketty 2014). However, unlike the intergenerational transmission of education and income, we know relatively little about the determinants of intergenerational wealth mobility, even though wealth may be a better measure of economic success than income or education. Wealth directly influences consumption and investment possibilities, and greater wealth loosens parents’ budget constraints, which may enable them to invest more in their children’s human capital.

Why is wealth correlated across generations? One possible pathway is through biology (nature) – the genetic inheritance of skills, attitudes, and preferences that correlate with higher wealth in each generation. This channel suggests that intergenerational correlations arise because children from wealthy families are inherently more talented and would be wealthier than others even without the advantage of growing up with wealthier parents.

Another pathway is environment (nurture) – wealthier parents may invest more in their children’s human capital, help their children get better jobs, provide funding for business start-ups, give financial gifts, or influence children’s preferences and attitudes. This pathway suggests that intergenerational correlations arise through opportunities provided by the environment the child is raised in, and any child given these opportunities would benefit. These two forces may interact, with environmental effects depending on biological endowments. The nature-nurture distinction is of great importance on the intergenerational wealth correlation as appropriate policy to address the high level of wealth inequality relies on an understanding of the underlying causes.

In recent research (Black et al. 2020), we attempt to disentangle the role of nature versus nurture and the role of nature-nurture interactions in the intergenerational transmission of wealth. Adoption allows us to examine the effects of environmental factors in a situation where adopted children have no genetic relationship with their adoptive parents. Using adoptees, we examine whether adoptive parent wealth or biological parent wealth better predicts a child’s wealth. We use Swedish administrative data on the net wealth and other characteristics of a large sample of adopted children born between 1950-1970 merged with similar information for their biological and adoptive parents, as well as corresponding data on own-birth children (children raised by their biological parents). We then merge this to Swedish wealth data collected for tax purposes between 1999-2006.

In our model, we assume that adoptees are randomly assigned to adoptive families at birth. The assumption will be violated if adoptees were systematically matched to adoptive parents that are similar to their biological parents. While matching of children to adoptive parents was at the discretion of the caseworkers, the evidence from that period suggests that social authorities were not able to systematically match babies to families based on family and child characteristics (Björklund, A., Lindahl, M., & Plug, E. 2006 and Lindquist, Sol, and Van Praag 2015). The fact that we can observe and control for the wealth rank of the biological parents mitigates these concerns. Additionally, previous studies using adoption data have shown that even when children are not assigned randomly to adoptive parents, the resultant biases are likely to be small.

In addition to studying wealth, we also examine whether the forces that drive intergenerational wealth transmission look similar to the ones driving the persistence of other economic outcomes such as income and education.

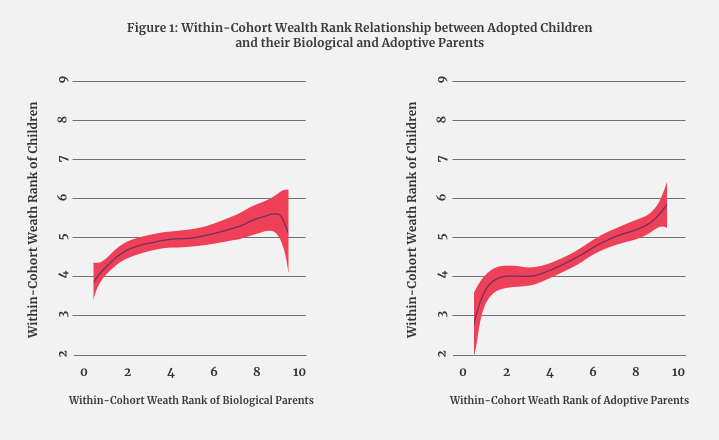

Figure 1 shows the relationship between a child’s net wealth and that of their biological and adoptive parents. We see that the relationships are approximately linear (meaning an increase in parental wealth is associated with a corresponding increase in child wealth), however the relationship between wealth of the child and the wealth of adoptive parents is stronger than the equivalent relationship with the wealth of the biological parents.

Even before any inheritance has occurred, wealth of adopted children is more closely related to the wealth of their adoptive parents than to that of their biological parents. This suggests that wealth transmission is primarily due to environmental factors rather than because children of wealthy parents are inherently more talented. When we examine the role played by bequests, we find that once they are taken into account, the role of environment becomes even stronger.

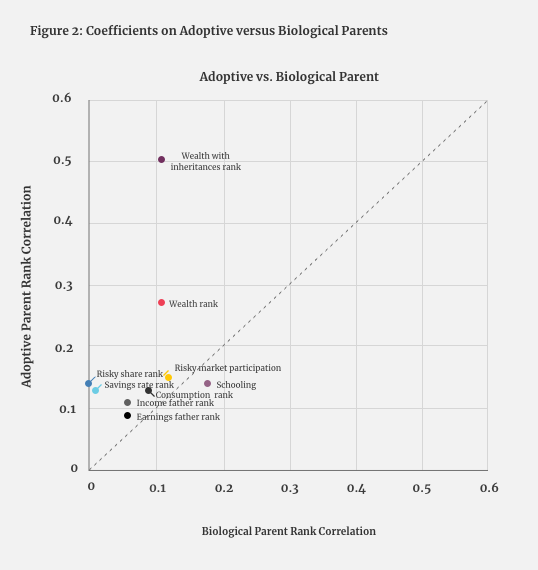

We find interesting differences when comparing the intergenerational transmission of wealth to that of other outcomes. In Figure 2, we plot the biological and adoptive coefficients for the variables studied. Points above the 45-degree line imply a larger role for environment (adoptive parent); points below the line imply a greater role for biology (biological parent). Consistent with other research, human capital linkages between parents and children appear to have stronger biological than environmental roots, suggesting a potentially important role for innate ability. Earnings and income are more environmental, suggesting that persistence in earnings and income across generations is not pre-ordained but a function of opportunity at birth. Outcomes and behaviors that are more directly related to wealth, such as savings and investment behavior, are disproportionately environmental – with wealth including inheritances most related to environment. The difference in results between the transmission of wealth and human capital is striking, and the greater environmental contribution in the transmission of wealth is consistent with dynasties that transfer wealth and labor market advantages across generations regardless of abilities.

When examining consumption, which might be viewed as a measure of welfare that is less sensitive to temporary fluctuations than income or wealth, we find both biological and somewhat larger environmental influences.

Our results suggest that the children of wealthy, high-consuming parents benefit not just from good genetics but, more importantly, from being raised with more advantages. As wealth and consumption become more unequally distributed, children from poorer families have fewer opportunities relative to children from wealthier families, suggesting a potential role for policy to equalize opportunities and mitigate intergenerational disparities. We find this is true in Sweden – a relatively egalitarian society – suggesting it is likely even more prevalent for a more unequal society such as the United States.