Summary

We use data on every police report in Finland linked to administrative records on employment, income, and demographic characteristics to identify the consequences of between-colleague violence on victims, perpetrators, and co-workers. The overwhelming majority of perpetrators of between-colleague violence are men, while victims are evenly split on gender lines.

We analyze between-colleague violence involving a male perpetrator and male victim (male-male violence) separately from those involving a male perpetrator and female victim (male-female violence). We find significant differences in the demographic characteristics of the workers involved and the seriousness of the incidents reported. While victims and perpetrators of male-male violence are of a similar age, income, and seniority within the firm on average, this is not the case for male-female between-colleague violence. Victims of male-female violence are younger and earn 30% less per year than their male perpetrators. The types of crimes that characterize male-female between-colleague violence are also more serious than those for male-male violence.

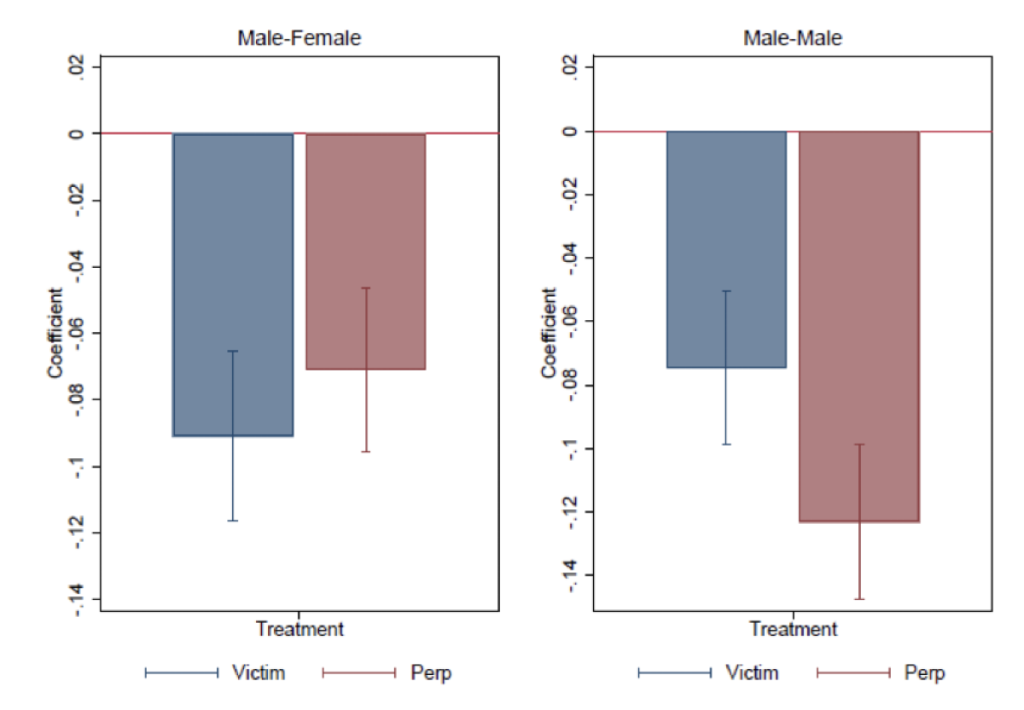

To identify the impact of between-colleague violence on outcomes, we compare the evolution of victims’ and perpetrators’ economic outcomes before and after the incident to observationally identical workers who were not affected by a workplace assault. We find that perpetrators of male-male violence face significantly larger economic penalties than their victims: 12.3 percentage points versus 7.5 p.p. In contrast, employment falls are larger for victims in the case of male-female crimes: perpetrators’ employment falls by 7.1 p.p., compared to a 9.1 p.p. fall for victims.

We also show that male-female violence has consequences for the wider workforce of these firms. Following male-female violence, the share of women employed by male-managed firms falls almost 6 p.p. In contrast, female-managed firms avoid this decline in female employees. This is partly explained by the fact that perpetrators are more likely to leave employment following a violent incident in female-managed firms.

Our results highlight the significant economic repercussions of workplace violence on both individual workers and the broader firm. These results suggest that policies that promote effective mechanisms for reporting workplace violence, that reduce gender inequality in the workplace, and that increase female representation in managerial positions could all help mitigate the repercussions of violence against women at work.

Main article

Despite the #MeToo movement, there is little evidence on the impacts of workplace violence on perpetrators and victims. This study looks at between-colleague violence in Finland and finds that these incidents have significant repercussions on both individual workers and the broader firm. There are significant differences between male-male violence and male-female violence, including, for example, that perpetrators in male-male crimes experience significantly greater negative economic repercussions compared with men who attack their female colleagues. For both categories, however, having power within the firm allows perpetrators to avoid more severe consequences, while their victims experience worse outcomes. The broader impacts of violence against women within firms are exacerbated by power imbalances in management.

The international #MeToo movement demonstrated the prevalence of between-colleague violence, and especially violence against women at work. Yet evidence was lacking on the impacts of workplace violence on perpetrators and victims, how these impacts may depend on power and gender differences, and the impacts on the broader firm. Our research harnesses unique Finnish administrative data to analyze the impact of violence between colleagues on victims, perpetrators, and the broader firm.

Data and Methodology

Our measure of between-colleague violence captures the population of violent incidents that occur between colleagues and are reported to the police. Specifically, we link every victim and perpetrator in the police data to their demographic and employment information in the Finnish Linked Employer-Employee Data. We define a police-reported violent crime as between-colleague violence if both the victim and perpetrator worked at the same plant in the year preceding the incident. Note that the reported incidents do not need to occur in the workplace itself. This means our measure will capture, for example, individuals assaulted by colleagues at off-premises holiday parties, when traveling for work, etc. However, our measure will miss incidents that are not reported to the police. We will therefore understate the true prevalence of between-colleague violence in the population and likely capture the most serious incidents. While these are important limitations, our estimates provide a first step in understanding the consequences of workplace assaults.

The international #MeToo movement demonstrated the prevalence of between-colleague violence, and especially violence against women at work.

Using this approach, we identify over 4,600 cases of violence between colleagues, and collect employment and earnings trajectories of victims and perpetrators before and after an incident. We additionally use plant identifiers to construct broader firm outcomes, focusing specifically on the gender composition of the workforce. We find that approximately half of the victims are women, while 84% of perpetrators are men. As a result, we focus on incidents with male perpetrators due to the small number of female perpetrators. While on average victims and perpetrators of male-male between-colleague violence are of a similar age and income, this is not the case for male-female between-colleague violence. Victims of male-female violence are younger and earn 30% less per year than their male perpetrators. The types of crimes that characterize male-female between-colleague violence are also more serious than those for male-male violence, with a higher share of assault and menace offenses for incidents involving a female victim. We do not find big differences in the characteristics of firms in which between-colleague violence occurs and other firms.

To estimate the impacts of between-colleague violence, we must contend with the fact that perpetrators might target economically vulnerable colleagues, or might themselves be struggling in the firm and lash out as a result. We employ a matched difference-in-differences design with individual fixed effects to compare the evolution of employment and earnings outcomes of affected workers before and after workplace violence to observationally identical workers who were not affected. Formally, we find a victim’s (and perpetrator’s) closest match based on their age, education level, gender, managerial status, employment, and income history in the five years before the incident. To compare how the consequences of being assaulted by a colleague differ from being attacked by someone outside the firm, we also compare the outcomes of between-colleague violence victims to observationally identical victims who are assaulted by non-colleagues as an alternative “violent” counterfactual exercise.

We identify over 4,600 cases of violence between colleagues, and collect employment and earnings trajectories of victims and perpetrators.

Impacts of Between-Colleague Violence on Victims and Perpetrators

We find that both victims and perpetrators experience an immediate drop in their labor market outcomes following between-colleague violence that persists for at least five years following the incident. Figure 1 shows that perpetrators in male-male crimes experience significantly greater negative economic repercussions than their victims and compared with men who attack their female colleagues. Employment rates in male-male crimes fall by 12.3 percentage points (p.p.) for perpetrators and 7.5 p.p. for victims. In contrast, employment in male-female crimes falls by 7.1 p.p. for perpetrators, and 9.1 p.p. for victims.

The limited economic consequences for male colleagues assaulting their female co-workers are also evident when one considers the counterfactual of violence between non-colleagues. In the case of male-male violence, perpetrators and victims face similar employment losses when they do and do not work in the same firm (but are otherwise observationally identical). However, perpetrators who attack women suffer significantly smaller employment losses when they are employed in the same firm as their female victim. On the other hand, female victims suffer greater employment losses when they are attacked by someone within the firm compared to a non-colleague.

Figure 1: Asymmetry in Employment Impacts of Workplace Violence

Notes: Left-hand figure reports estimates for male-female violence for victims (in the blue bar on the left) and perpetrators (in the red bar on the right). The right-hand figure provides the same estimates for male-male violence. Panel A reports impacts on employment while Panel B reports impacts on labor market income. 95% confidence intervals are depicted in whiskers around the estimates. Employment indicates whether the individual was employed in the last week of the year. Income is total taxable labor market income (the sum of salary, wages, and self-employment earnings) after the event as a fraction of the average total income in the 5 years prior. Standard errors are clustered at the individual level.

Both victims and perpetrators experience an immediate and persistent drop in their labor market outcomes following between-colleague violence.

The Important Role of Power Discrepancies Between Victim and Perpetrator

When describing the aftermath of her assault at the hands of Harvey Weinstein, Rowena Chiu wrote in her New York Times editorial: “Harvey was a power player, and I was the lowest person on the totem pole. Assistants are the unseen work force that props Hollywood up, and yet we have zero leverage. I was invisible and inconsequential.” (Chiu, 2019). Motivated by such high-profile anecdotal accounts from MeToo, which suggest that being attacked by someone with power in the firm is especially problematic, we explore power differentials between victims and perpetrators as one possible explanation for the asymmetric effects between male-male and male-female between-colleague violence.

We find that victims face larger employment losses both when perpetrators are managers and when there is a greater income gap between the victim and perpetrator. For perpetrators, the effect is the opposite: their employment rates are less severely affected when they occupy positions of relative power within the firm. For male-female (male-male) crime, victims’ employment rates fall by 7 (6.3) p.p. more when their perpetrator is a manager. However, perpetrators who are managers are 6 (13.7) p.p. less likely to be unemployed in the five years following an incident. Thus, power within the firm allows perpetrators to avoid more severe consequences, while their victims experience worse outcomes. This pattern is true for both male-female violence and male-male violence. However, we find that perpetrators who assault female colleagues are significantly more likely to be managers or high earners in the firm compared with perpetrators who assault male colleagues.

Perpetrators in male-male crimes experience significantly greater negative economic repercussions compared with men who attack their female colleagues.

Impacts on the Firm

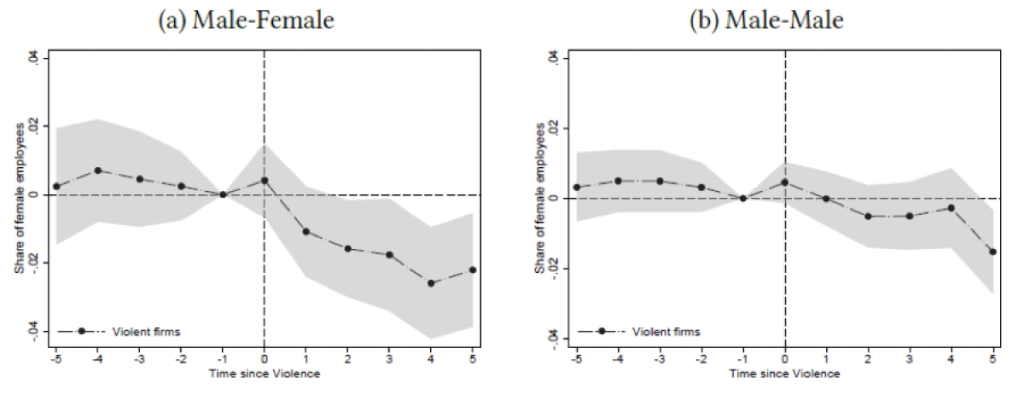

Last, we investigate the broader implications of between-colleague violence for the firm. Figure 2 (a) demonstrates that after an incident of male-female workplace violence, there is a significant decline in the proportion of women employed in these firms relative to a matched control firm. The effect is quantitatively large and persistent: relative to the pre-incident mean, the share of women employed by the firm falls over 2 p.p. by five years after the incident. Figure 2 (b) demonstrates that this effect is isolated to firms where male-female violence occurs. The fall in the share of women employed by the firm is driven both by incumbent women being more likely to leave the firm than incumbent men and by an increase in the proportion of men amongst new hires.

Figure 2: Impact on Share Female Employees in the Firm

Notes: Left-hand figure shows the impact of a violent incident between colleagues on the share of female workers at the firm in which both perpetrator and victim were employed at the time of the incident for male-female between-colleague violence. The right-hand figure shows the same impact but for male-male between-colleague violence. The estimates use the matched control DiD design to identify effects 5 years before and 5 years after a violent incident against a colleague. The horizontal axis displays time in years. Dashed vertical lines indicate the year of between-colleague violence. Standard errors are clustered at the firm level.

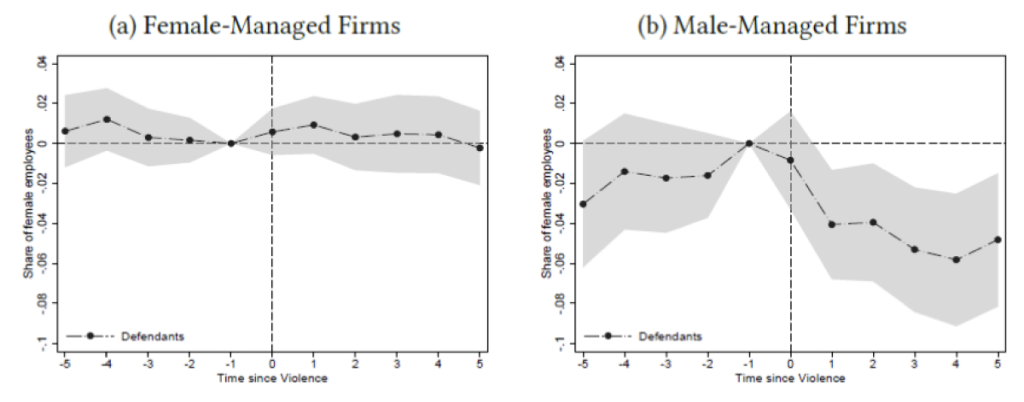

Firm differences in management could mediate or accentuate the impact of workplace violence on the wider workforce. To explore this, we consider heterogeneity in the impact of male-female violence on the share of female workers in male-managed versus female-managed firms. Following Bender et al. (2018), we identify workers in the top 20% of earners in the firm as those with decision-making power. If the proportion of women in the top 20% is above the median, we label the firm female managed.

Power within the firm allows perpetrators to avoid more severe consequences, while their victims experience worse outcomes.

Figure 3 shows that while there is a significant decline in the share of female employees following an incident of male-female violence in male-managed firms relative to their matched control, we see no significant impact on the share of female employees for female-managed firms. The persistence and size of the loss of women in male-managed firms is particularly striking: we observe an almost 6 p.p. decline in the share of women employed in male-managed firms by five years after male-female violence. This effect is quantitatively significant relative to the baseline share of women employed in these firms, which is 24.1%.

Figure 3: Impact on Share Female Employees By Firm Management for Male-Female Crimes

Notes: Figure shows the impact of male-female violence on the share of female workers in the firm separately for female-managed firms (left-hand figure) versus male-managed firms (right-hand figure). We define management as “male” if the share of men in the top 20% of earners is above the median share, and “female” otherwise. Standard errors are clustered at the firm level.

How does female management mediate the impact of male-female violence on the broader workforce? Motivated by the relative lack of consequences for men who attack female colleagues, we analyze the relationship between female management and the employment of perpetrators. We find that perpetrators have significantly lower employment rates following a violent incident in female-managed firms: for male-female (male-male) violence, perpetrators in female-managed firms have an approximately 5.5 (8.4) p.p. greater reduction in employment compared to their matched control and relative to male-managed firms.

Gender inequality and power imbalances in management exacerbate the broader impacts of violence against women within firms.

Next, we examine the impact of perpetrators losing their jobs on the share of women employed in the firm following male-female violence. We show that perpetrators losing their jobs in female-managed firms plays a significant role in reducing the impact of male-female violence on the share of women employed in these firms. We further find that female-managed firms where the perpetrator remains employed also have different outcomes from male-managed firms (p-value=0.081), suggesting that there are additional aspects of female management that help mitigate the loss of female talent when there is violence against a woman at the firm.

Policy Implications

Given the significant repercussions we document of workplace violence on individual workers and the broader firm, policies establishing and promoting effective mechanisms for reducing workplace violence and ensuring that any incidents are properly addressed are warranted. Firms should also implement preventive measures, such as awareness campaigns, training, and protections for those who come forward, to create a safer working environment. Our results also suggest that gender inequality and power imbalances in management are key mechanisms that exacerbate the broader impacts of violence against women within firms. Policies empowering women in managerial roles could mitigate the costs of violence against women at work and increase the representation of women throughout these firms.

This article summarizes ‘Violence Against Women at Work’ by Abi Adams-Prassl, Kristiina Huttunen, Emily Nix, and Ning Zhang, published in The Quarterly Journal of Economics in September 2023.

Abi Adams-Prassl is at the University of Oxford, Kristiina Huttunen is at Aalto University, Emily Nix is at the University of Southern California, and Ning Zhang is at the Chinese University of Hong Kong.

References

Bender, S., Bloom, N., Card, D., Van Reenen, J. And Wolter, S. (2018). Management Practices, Workforce Selection, and Productivity. Journal of Labor Economics, 36 (S1), S371–S409.

Chiu, R. (2019). I Can Finally Tell My Weinstein Story. New York Times, p. 7.