The Berlin Wall provides a unique natural experiment for identifying the key sources of urban development. This research, for which its authors have recently been awarded the prestigious Frisch Medal, shows how property prices and economic activity in the east side of West Berlin, close to the historic central business district in East Berlin, began to fall when the city was divided; then, during the 1990s, after reunification, the same area began to redevelop. Theory and empirical evidence confirm the positive relationship between urban density and productivity in a virtuous circle of ‘cumulative causation’. The analysis has practical applications for urban planners making decisions on housing and transport infrastructure.

Economic activity is highly unevenly distributed across space. This is reflected in the existence of cities and the concentration of economic functions in specific locations within cities, such as Manhattan in New York and the Square Mile in London.

Understanding the strength of the forces of agglomeration and dispersion that underlie these concentrations of economic activity is central to a range of economic and policy questions. These forces shape the size and internal structure of cities, with implications for the incomes of immobile factors, congestion costs and urban productivity. They also determine the impact of public policy interventions, such as investments in transport infrastructure as well as urban development and taxation policies.

Agglomeration, dispersion and locational fundamentals

Although much has been written about economic geography and urban economics dating back at least as far as Alfred Marshall’s Principles of Economics, published in 1920, a central challenge remains: distinguishing the impact of the forces of agglomeration and dispersion from the impact of differences in the fundamental characteristics of locations.

High land prices and levels of economic activity in a group of neighbouring locations are consistent with strong agglomeration forces. But they are also consistent with shared amenities that make these locations attractive places to live – such as leafy streets and scenic views – or common natural advantages that make these locations attractive for production – such as access to natural water.

This challenge has both theoretical and empirical dimensions. From a theoretical perspective, to develop tractable models of cities, the existing body of research typically makes simplifying assumptions, which abstract from variation in locational fundamentals and limits the usefulness of these models for empirical work.

From an empirical perspective, the challenge is to find exogenous sources of variation in the surrounding concentration of economic activity to help disentangle agglomeration and dispersion forces from variation in locational fundamentals.

Internal city structure

Our research develops a quantitative theoretical model of internal city structure. The model incorporates agglomeration and dispersion forces and an arbitrary number of heterogeneous locations within the city, while remaining amenable to empirical analysis:

- Locations differ in terms of productivity, amenities, the density of development (which determines the ratio of floor space to ground area) and access to transport infrastructure.

- Productivity depends on production externalities, which are determined by the surrounding density of workers, and production fundamentals, such as topography and proximity to natural supplies of water.

- Amenities depend on residential externalities, which are determined by the surrounding density of residents, and residential fundamentals, such as access to forests and lakes.

- Congestion forces take the form of an inelastic supply of land and commuting costs that rise with travel time, which in turn depends on the transport infrastructure.

The analysis remains tractable despite the large number of asymmetric locations, because we allow workers’ commuting decisions to depend on idiosyncratic random shocks to preferences, as well as economic forces such as wages and the cost of living.

This model of commuting decisions provides microfoundations for a ‘gravity equation’ for commuting, in which commuting flows depend on workplace characteristics (such as wages), residence characteristics (such as the cost of living) and bilateral commuting costs. We show that the gravity equation provides a good approximation to observed commuting flows.

The division and reunification of Berlin

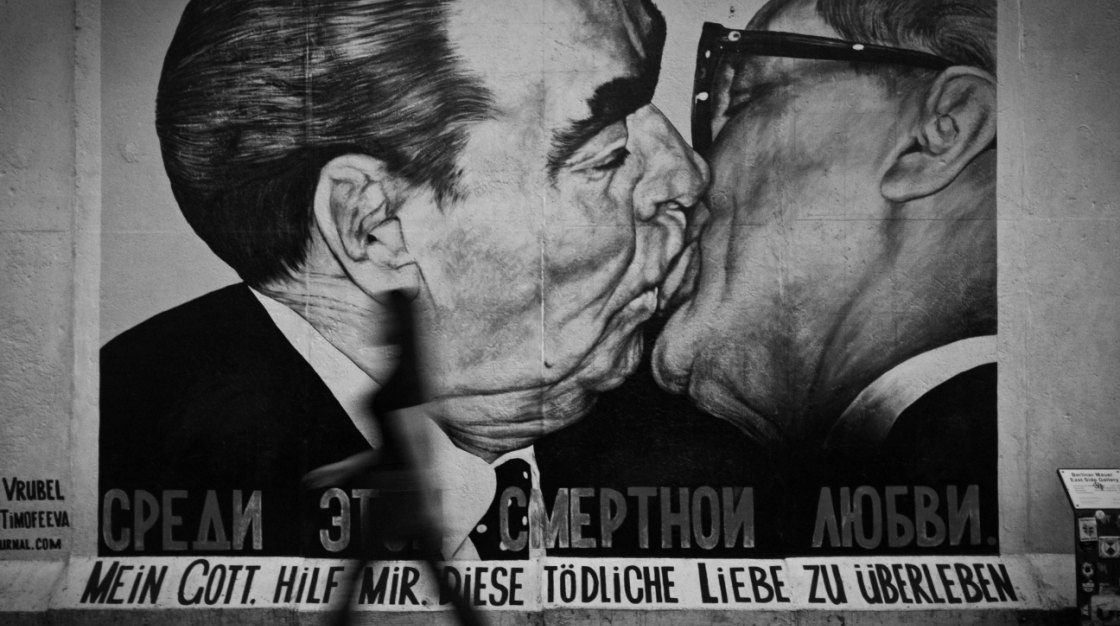

We combine our quantitative theoretical model with the natural experiment of Berlin’s division in the aftermath of the Second World War and its reunification following the fall of the Iron Curtain. The division of the city severed all local economic interactions between East and West Berlin, which corresponds in the model to prohibitive trade and commuting costs and no production and residential externalities between these two parts of the city.

Berlin’s division and reunification provides a natural experiment for modelling the organization of economic activity within cities

To provide evidence on the resulting impact on the organization of economic activity within the city, we make use of a remarkable and newly collected data set for Berlin, which includes data on land prices, employment by place of work (which we term ‘workplace employment’), and employment by place of residence (which we term ‘residence employment’) covering the pre-war, division and reunification periods.

We focus largely on West Berlin, since it remained a market economy in all three of these periods, and hence we would expect the market-based mechanisms in the model to be at work.

We first present evidence that division led to a reorientation of the gradient in land prices and employment in West Berlin away from the main pre-war concentration of economic activity in East Berlin, while reunification led to a re-emergence of this gradient. In contrast, there is little effect of division or reunification on land prices or employment along other more economically remote sections of the Berlin Wall.

As Panel A of Figure 1 shows, Berlin’s land price gradient was approximately ‘monocentric’ prior to the Second World War, with the central business district located in the district ‘Mitte’ – just east of the future line of the Berlin Wall. Around this central point, there were concentric rings of progressively lower land prices, including two areas in the future West Berlin – one around the Kurfuerstendamm and the other just west of the future line of the Berlin Wall, close to the Anhalter Bahnhof (see Panel B).

Following the division of Berlin, the second of these land price peaks was eliminated, as this area around the former Anhalter Bahnhof ceased to be an important centre of commercial and retail activity (see Panel C).

Following the reunification of Berlin, there was a re-emergence of high land price values in the pre-war central business district in Mitte (see Panel D) and in areas of West Berlin close to the pre-war central business district (see Panel E). Those parts of the city suddenly had access to all the knowledge and public resources in the resurgent central business district that they had been denied, spurring development and boosting land prices.

Changes in the organization of economic activity

We next examine whether our model can account quantitatively for these observed changes in the organization of economic activity.

First, we use the model’s gravity equation for commuting flows to estimate its commuting parameters and determine overall measures of productivity, amenities and the density of development for each block, without making any assumptions about the relative importance or functional form of externalities and fundamentals as components of productivity and amenities.

Second, we use exogenous variation from Berlin’s division and reunification to estimate jointly the model’s agglomeration and commuting parameters. This allows us to decompose overall productivity and amenities for each block into production and residential externalities (which capture agglomeration forces) and production and residential fundamentals (which are structural residuals that ensure the model rationalizes the observed data).

Our identifying assumption is that changes in these structural residuals are uncorrelated with the exogenous change in the surrounding concentration of economic activity induced by Berlin’s division and reunification.

This identifying assumption requires that the systematic change in the pattern of economic activity in West Berlin following division and reunification is explained by the mechanisms of the model (the changes in commuting access and production and residential externalities) rather than by systematic changes in the pattern of structural residuals (production and residential fundamentals)

Our estimates of the model’s parameters imply substantial and highly localized production externalities.

We estimate that a 1 percent increase in the density of workplace employment raises productivity by 0.07 percent, which is towards the high end of the range of existing estimates using variation between cities. But we also find that production externalities are highly localized within the city, decaying to close to zero after around 10 minutes of travel time.

Therefore, as an increase in total city population is typically achieved by a combination of an increase in the density of economic activity and an expansion in geographical land area, the resulting increase in travel times from a larger geographical land area attenuates the magnitude of these production externalities.

We also estimate that a 1 percent increase in the density of residence employment raises amenities by 0.15 percent, which is consistent with the view that consumption externalities are an important agglomeration force in addition to production externalities. Again we find that these consumption externalities are highly localized, decaying to close to zero after around 10 minutes of travel time.

Evaluating public policy interventions

We show how our model can be used to undertake counterfactuals for both the impact of division and reunification and other public policy interventions, such as changes in transport infrastructure.

We show that a special case of the model with exogenous productivity and amenities is unable to account quantitatively for the observed effects of division and reunification. In contrast, the model with the estimated agglomeration and dispersion forces generates predictions for the reorganization of economic activity within West Berlin close to the patterns observed in the data.

As an illustration of the model’s potential for evaluating changes in transport infrastructure, we examine the impact of eliminating the automobile as an alternative to public transport within Berlin. In particular, we use the model to solve for the counterfactual equilibrium distribution of economic activity in 2006 using travel time measures based solely on the public transport infrastructure in 2006.

As a result of this deterioration in transport technology, the average travel time increases from around 32 to 38 minutes, where we weight travel times by the actual bilateral commuting flows in the 2006 equilibrium. But the response of the economy to this deterioration in commuting technology is that locations become less specialized in workplace and residence activity.

A corollary of this decline in specialization is a change in the pattern of worker sorting across bilateral pairs of workplace and residence locations. Even though travel times for any bilateral pair have increased, we find that this change in worker sorting results in marginally lower average travel times of around 30 minutes in the counterfactual equilibrium, where we now weight travel times by the commuting flows in the counterfactual equilibrium. Intuitively, in response to the worse commuting technology, economic activity reallocates such that in the new equilibrium the average worker spends about the same time commuting but travels a shorter distance.

Concluding remarks

We develop a tractable quantitative framework for modelling the organization of economic activity within cities that allows a role for both differences in locational fundamentals and agglomeration forces. We use Berlin’s division and reunification as a natural experiment to estimate the model’s parameters.

We find that the estimated model is able to account for the resulting reorganization of economic activity within Berlin, not only qualitatively but also quantitatively. We show that our framework provides a tractable platform for evaluating a range of public policy interventions, including changes in transport infrastructure.

Our research highlights the importance of endogenous changes in the organization of economic activity within cities in evaluating the impact of these public policy interventions.

This article summarizes ‘The Economics of Density: Evidence from the Berlin Wall’ by Gabriel Ahlfeldt, Stephen Redding, Daniel Sturm and Nikolaus Wolf, published in Econometrica 83(6), November 2015: 2127-89. The authors of the paper have been awarded the 2018 Frisch Medal by the Econometric Society.