Summary

Concerns in some quarters about the number of low-skill migrants coming to the United States in recent years have led to proposals for stricter immigration policies, including preferences for high-skill workers and the construction of a wall on the US border with Mexico.

New research provides a framework for assessing who would lose and who would gain from such policies. The analysis considers the impact on the wages of high- and low-skill native workers in the ‘gateway cities’ to which the immigrants come, on the wages of the existing stock of immigrants, on local housing costs, and on internal migration, which transmits some of the effects to other parts of the country.

The results first indicate that a skill-selective immigration policy similar to the UK’s would lead to a 46% increase in high-skill immigrants. In those circumstances and before taking account of internal migration, the average wages of low-skill workers initially rise by about 4% in gateway cities that receive a larger portion of the new high-skill immigrants, while the average wages of low-skill workers in other cities rise, on average, by 1-2%.

Furthermore, there are small positive effects on the wages of high-skill natives in most locations, while the wages of incumbent high-skill immigrants fall substantially in all locations. A 1% increase in a city’s population due to immigration is also associated with approximately a 1% increase in average housing rents.

When the analysis allows for free internal migration, the negative impacts on the average welfare of high-skill natives and high-skill immigrants in gateway cities are attenuated. Indeed, the gains are equivalent to an almost $1,000 increase in annual consumption for high-skill natives in gateway cities.

Next, the study evaluates a skill-neutral policy, one that increases the stock of immigrants by the same amount as the skill-selective policy, but maintains the US skill composition of immigrants as in 2007. In this case, the arrival of new immigrants has more positive wage effects on high-skill natives and less negative wage effects on high-skill immigrants.

The third policy experiment examines the effects of a border wall between the United States and Mexico. The study shows that even if the wall were to reduce the inflow of potentially illegal immigrants by 80%, any wage or rent effects are rather small and become negligible as workers relocate. In all cases, the benefits would still be significantly lower than the cost of construction.

Finally, there is a significant increase in rental income accruing to landlords from increased immigration. This suggests that an appropriate tax scheme on rental income would be an important consideration if policy-makers want to redistribute the gains and losses from immigration more evenly.

Overall, the findings show, even after worker relocation, the welfare impact of immigration is unevenly distributed across and within cities. This highlights the importance of studying the welfare consequences of immigration at the local labor market level.

Main article

Concerns in some quarters about the number of low-skill migrants coming to the United States in recent years have led to proposals for stricter immigration policies, including preferences for high-skill workers and the construction of a wall on the US border with Mexico. This column reports the findings of a recent study of the effects of immigration, which assesses the distributional consequences of these policies. The analysis considers the impact on the wages of high- and low-skill native workers in the ‘gateway cities’ to which the immigrants come, on the wages of the existing stock of immigrants, on local housing costs, and on internal migration, which transmits some of the effects to other parts of the country.

Immigration has been a central political debate in the United States for decades, in part because of public concerns about its magnitude and its composition. For example, in the early 2000s, around 1.25 million immigrants arrived each year (Card, 2009). The share of immigrants in the US working-age population increased from 10% in 1990 to about 17% in 2007. And at least a third of the new immigrants are undocumented, with little education and limited English language skills (Passel, 2005).

There are substantial variations in the welfare effects of immigration across and within cities

The number and characteristics of recent immigrants have led to policy proposals that include building a border wall between the United States and Mexico and reforming the program of high-skill immigrant visas. Who would lose and who would gain from these policies? These questions are complex because the local effects of immigration may differ from effects at the national level – and they may vary substantially across cities since some parts of the country attract more immigrants than others.

The local effects can also vary across workers. Intuitively, immigrants may put upward pressure on the wages of complementary labor and downward pressure on the wages of substitute labor. For example, an inflow of low-skill immigrants may raise the wages of high-skill workers and lower the wages of the incumbent low-skill workers, while an inflow of high-skill immigrants may have the opposite effects.

These effects need not fall on workers of a particular skill group equally. Other characteristics, such as gender and nativity status (whether or not someone was born in the United States), may make workers imperfect substitutes in production and hence unequally affected.

Furthermore, wages may not capture the full welfare effects of immigration. Any wage gains may be offset, or losses amplified, by rising housing costs due to immigration.

A skill-selective immigration policy leads to welfare gains for low-skill workers, but welfare losses for high-skill workers

An inflow of new arrivals may also induce internal migration. The induced migration could modify the local impact as well as transmitting immigration shocks to other cities. Thus, even within a city, workers can be affected by immigration differently due to heterogeneity in their characteristics and degrees of internal mobility.

Modeling the effects of immigration

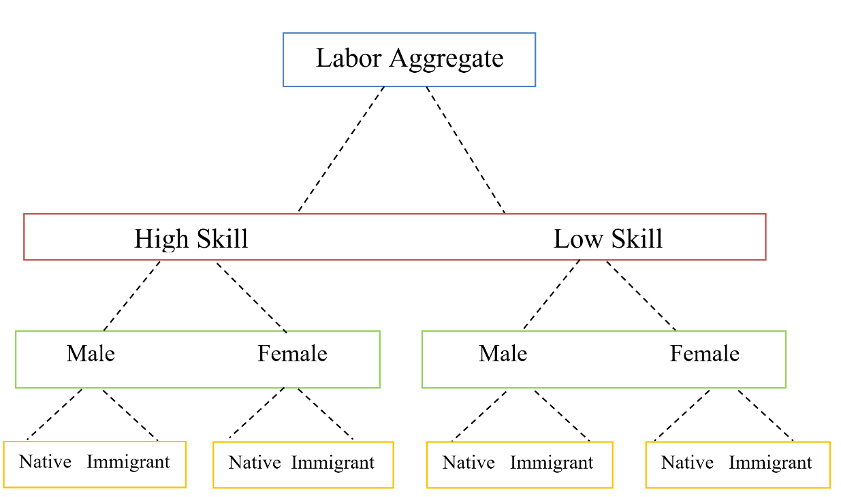

Given the linkages between cities through labor relocation, my research studies the welfare implications of immigration using a spatial equilibrium model. Since the impacts of immigration should depend on the degree of substitutability of labor, I allow workers of different characteristics to be imperfect substitutes.

To keep the framework tractable, firms are assumed to produce a single national product, but each local labor market can have city-specific productivity. Workers differ in skill level, gender, and birthplace. There is ample evidence that workers of different skill levels are imperfect substitutes.

To capture occupational differences in this single product set-up, I allow men and women to be imperfect substitutes given that they tend to work in different occupations.

The negative impacts are more substantial among incumbent high-skill immigrants

Finally, I allow for the possibility that immigrants and natives are imperfect substitutes, and their substitutability can vary by skill level. For example, immigrants might be closer substitutes to natives among low-skill labor since factors such as differences in the quality of education and English language skills may be less crucial.

Figure 1 illustrates the production function in this framework.

Figure 1: Production function

Cities differ in productivity levels, housing supply elasticities, and amenities. Preferences for city characteristics differ across workers. While all workers have access to the same local amenities, different groups of workers can value amenities differently. For example, amenities might be more important for the location choices of high-skill workers than low-skill workers.

Negative impacts on high-skill natives and immigrants in gateway cities are attenuated by internal migration

In addition, a well-known settlement pattern of new immigrants is that they tend to locate in country-specific enclaves (Altonji and Card, 1991). This could be because it is easier to move to a city where an immigrant has a larger network.

Therefore, I allow immigrants to value a city-specific network size proxied by the city’s number of previous immigrants born in the same country group. Given natives’ affinity with their birthplaces, I also allow natives to derive utility from living in or near the states in which they were born.

Evaluating a skill-selective immigration policy

Using US census data, the estimated model allows me to assess policies that would change the skill mix and stock of immigrants, as well as the benefits of the border wall between the United States and Mexico.

First, I consider the effects of the United States adopting a skill-selective immigration policy similar to the UK. Such a policy would lead to a 46% increase in high-skill immigrants.

I find that the average wages of low-skill workers initially rise by about 4% in ‘gateway cities’ that receive a larger portion of the new high-skill immigrants, while the average wages of low-skill workers in other cities rise, on average, by 1-2%. The wage increase is due to the complementarity between high- and low-skill labor.

There are small positive effects on the wages of high-skill natives in most locations, while the wages of incumbent high-skill immigrants fall substantially in all locations. The differential wage effects between immigrants and natives are due to their imperfect substitutability.

There is more emigration in response to new migrants from cities with larger shares of previous immigrants and natives who have already left their birthplaces

Further, a 1% increase in a city’s population due to immigration is associated with approximately a 1% increase in average housing rents.

Since immigration affects wages, rents, and relocation of some workers, I focus on the welfare impact taking account of all changes. To understand the role of internal migration, I consider two cases. One is the fixed migration case where the allocation of natives and immigrants across cities is held constant. The other is the free migration case where all workers make their location decisions simultaneously.

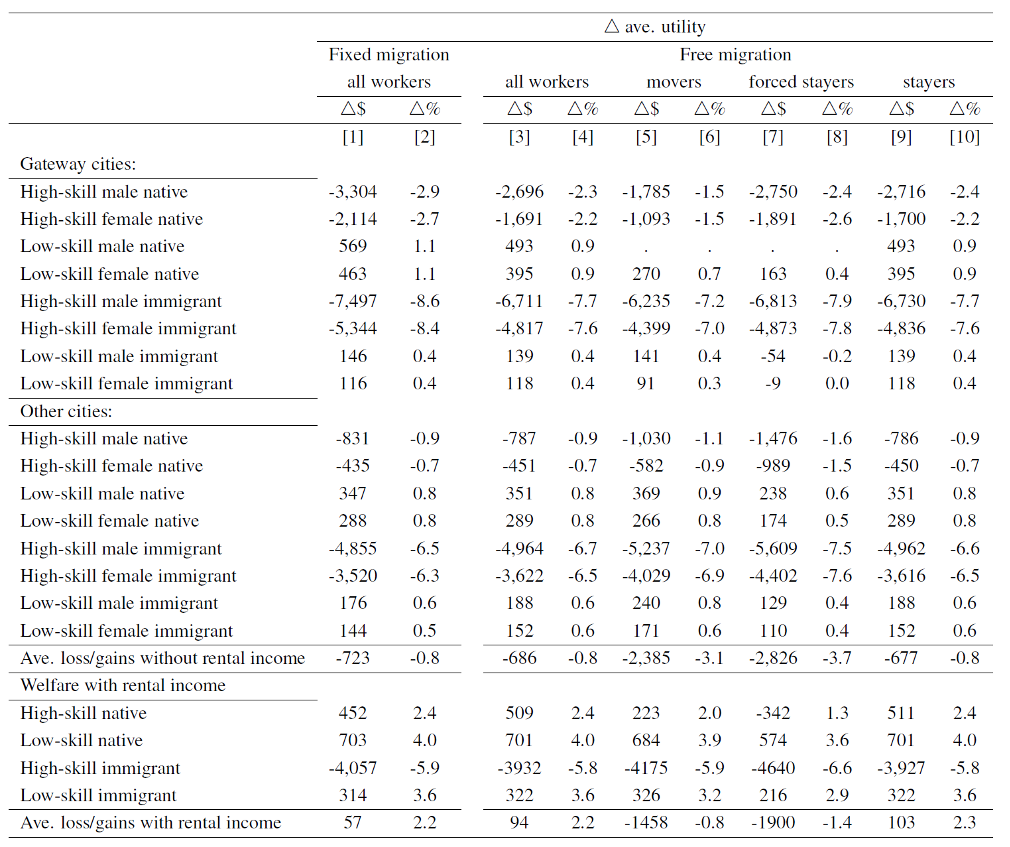

Table 1 reports changes in average welfare in annual wage units by worker characteristics in gateway and other cities under fixed and free migration. The columns labeled ‘Δ$’ show the change in the dollar amount, and the columns labeled ‘Δ%’ express the change as a percentage of welfare in the absence of the specified policy reform.

Table 1: Welfare effects of a skill-selective immigration policy

In the fixed migration case (columns 1 and 2), the average welfare impact on high-skill natives in gateway cities is equivalent to a reduction of almost 3% in annual consumption: $3,304 and $2,114 for high-skill men and women, respectively. The reduction is considerably more severe for high-skill immigrants, equivalent to around an 8% loss in annual consumption: $7,497 and $5,344 for men and women, respectively.

The impacts are less substantial in other cities. Among low-skill workers in gateway cities, average welfare improves by around 1% for natives ($569 and $463 for native men and women, respectively), and by 0.4% for their immigrant counterparts ($146 and $116 for men and women immigrants, respectively). The average gains for low-skill workers in other cities are similar to those in gateway cities.

In the free migration case, the negative impacts on the average welfare of high-skill natives and high-skill immigrants in gateway cities are attenuated. The welfare losses of those who move from gateway cities are substantially mitigated. This is shown in columns 5 and 7 of Table 1.

The difference between the change in welfare of movers and forced stayers represents the ‘gains from internal migration’. The gains are equivalent to an almost $1,000 increase in annual consumption for high-skill natives in gateway cities. The welfare gains for low-skill natives become slightly smaller.

The potential benefits of a border wall between Mexico and the United States are much smaller than the costs of construction

Overall, even after worker relocation, the welfare impact of immigration is unevenly distributed across and within cities, which highlights the importance of studying the welfare consequences of immigration at the local labor market level. The additional rental income accruing to landlords is sizable, and it could on average result in welfare gains if redistributed.

Evaluating a skill-neutral immigration policy

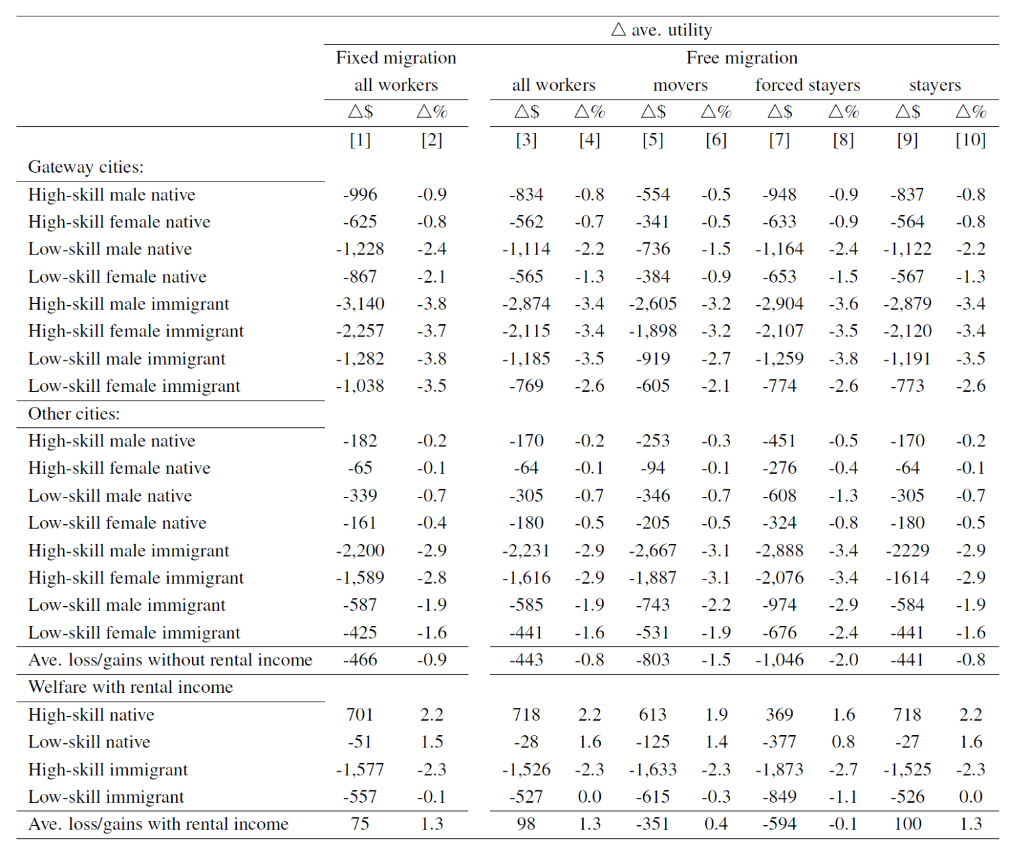

Next, I evaluate a skill-neutral policy, one that increases the stock of immigrants by the same amount as the skill-selective policy, but maintains the US skill composition of immigrants in 2007. This involves a 25% increase in immigrants.

Table 2 reports the changes in average welfare under the skill-neutral policy. The arrival of new immigrants has more positive wage effects on high-skill natives and less negative wage effects on high-skill immigrants relative to the skill-selective policy.

This is because a larger portion of new immigrants in this case is low-skill, and so the negative wage effect is counterbalanced by the complementarity between high- and low-skill labor. But the rising housing costs lead to a decline in the welfare of both low- and high-skill workers.

Nevertheless, because all workers are free to migrate within the United States, the negative impacts in some cities are attenuated. The migration responses of low-skill workers to this second policy are more pronounced. This is because the most adversely affected group in this experiment is low-skill immigrants.

The out-migration responses of low-skill workers substantially reduce the initial negative wage and rent impacts in cities with inelastic housing supply, such as Miami, while intensifying the negative wage impacts in more affordable cities. The welfare gains from internal migration of movers are about 50% smaller than in the first counterfactual, and the additional rental income accruing to landlords is about 30% smaller.

Evaluating the welfare impact of a border wall

The final policy experiment examines the effects of a border wall between the United States and Mexico. The massive construction cost, as proposed by the Trump administration (Meckler, 2018), calls into question whether the benefits would outweigh the cost.

I simulate the effects of the wall on wages, rents, and welfare under a range of scenarios in which different fractions of an inflow of potentially illegal immigrants from Mexico in the adjacent US states are removed.

The results show that even if the wall were to reduce the inflow of potentially illegal immigrants by 80%, any wage or rent effects are rather small and become negligible as workers relocate. In all cases, the benefits from this policy would still be significantly lower than the cost of construction.

Conclusions

Overall, my research shows that there are substantial variations in the welfare effects of immigration across and within local labor markets. A ‘non-equilibrium’ analysis based on wages or local real wages that ignores migration within the United States and rents does not give a full representation of the welfare distribution.

Out-migration in response to new migrants tends to be stronger in cities with larger shares of previous immigrants and natives who have already left their birthplaces. Cities with lower productivity, more inelastic housing supply, or lower quality amenities are also more likely to have an outflow of incumbent workers. Internal migration leads to a more equalizing impact of immigration across locations.

Finally, there is a significant increase in rental income accruing to landlords from increased immigration. This suggests that an appropriate tax scheme on rental income would be an important consideration if policy-makers want to redistribute the gains and losses from immigration more evenly.

Table 2: Welfare effects of a skill-neutral immigration policy

This article summarizes ‘The Impact of Immigration on Wages, Internal Migration, and Welfare’ by Suphanit Piyapromdee (University College London), published in the Review of Economic Studies 88(1): 405-53, January 2021.