Summary

One of the most prominent aspects of inequality in the United States is the persistence of large racial economic disparities, of which a major component is the earnings difference between Black and white workers. This article demonstrates how the expansion of the minimum wage in 1967 played a critical role in closing the racial earnings gap and offers insights for reducing the large racial disparities that still exist today.

The earnings difference between Black and white workers fell dramatically in the United States in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Various explanations for the narrowing wage gap, such as the Civil Rights Act of 1964 or improvements in education for Black students, may explain part of the gap decline, but do not address its full magnitude. We present a new explanation for falling racial earnings gaps during this period: the extension of the federal minimum wage to new sectors of the economy. In 1967, amendments to the Fair Labor Standards Act extended minimum wage coverage to new sectors, such as farms, hotels, restaurants, schools, hospitals, nursing homes, and entertainment.

While white workers benefited from this reform, Black workers experienced even greater gains due to their overrepresentation in the newly covered industries and lower average earnings compared to their white counterparts. The earnings increase caused by the reform was 10 percent on average for Black workers in the newly covered industries, twice as much as for white workers.

We also examine how the 1967 minimum wage extension affected overall employment within industries covered under the reform. The difference in the number of workers earning less than the minimum wage prior to the reform and earning at or above the minimum wage after the reform is similar to the difference had there been no reform at all, suggesting a negligible effect on employment for Black and white workers.

The role of the 1967 minimum wage reform in advancing Black economic status during the Civil Rights Era provides further evidence that increased expansion of the minimum wage coverage could reduce the persistent earnings divide between white workers and Black, Hispanic, and Native American workers today.

Main article

This paper provides a new explanation for the dramatic decline in the U.S. racial earnings gap in the 1960s and 70s. We show that the 1966 Fair Labor Standards Act, which expanded the federal minimum wage to cover industries where nearly a third of Black workers were employed, significantly reduced racial economic disparities in the economy. Leveraging variation in reform timing and coverage, we show that earnings rose sharply for workers in the newly covered industries, and the impact was nearly twice as large for Black workers as for white workers—with no significant declines in employment. These findings suggest that minimum wage policy can play a critical role in reducing racial inequality today.

Last summer’s mass mobilization for racial justice sparked debates around how to combat entrenched racial inequality in the United States. Recent corporate diversity initiatives, while a step in the right direction, are not sufficient to topple structural racism in the economy. One of the most striking dimensions of inequality in the United States is the persistence of large racial economic disparities, of which a major component is the earnings difference between Black and white workers (Bayer and Charles, 2018; Chetty et al. 2020).

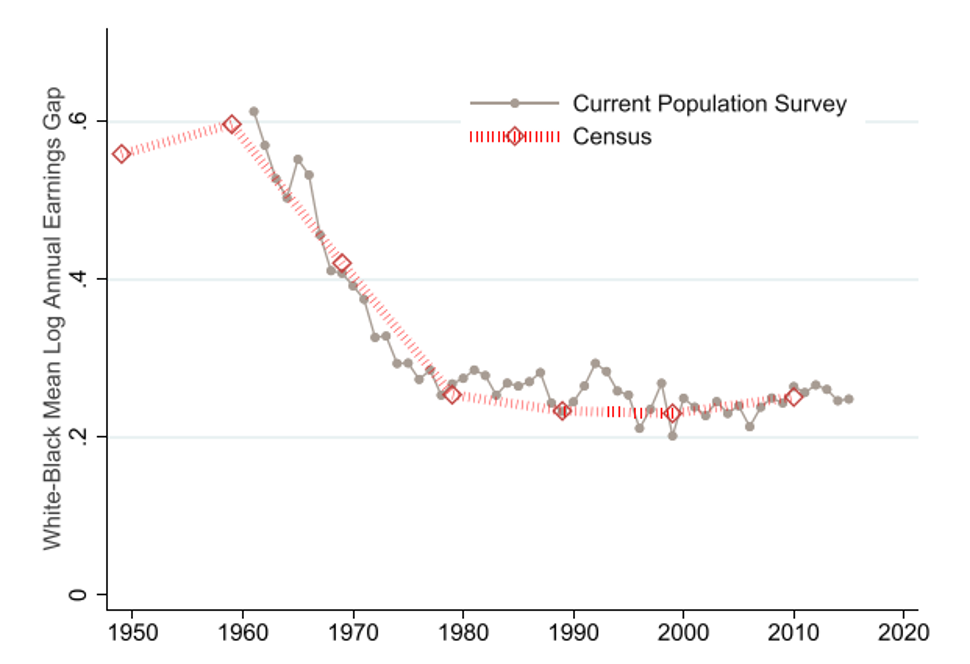

American history provides a prime example of when a simple public policy reform reduced racial inequality in the past. Understanding the factors behind this historical improvement may offer insights into spurring further racial economic progress today. Over the past 70 years, the racial gap fell significantly only once, during the late 1960s and early 1970s, when it was reduced by a factor of about two (Figure 1). This article demonstrates how the expansion of the minimum wage in 1967 played a critical role in reducing deep-rooted inequalities.

Figure 1: Economy-Wide white-Black Unadjusted Wage Gap in the Long Run, in the CPS and in the Decennial Censuses

1. Annual Social and Economic Supplement of the Current Population Survey, 1962–2016; U.S. Census from 1950 to 2000, and American Community Survey data in 2010 and 2017.

2. Sample: Adults 25–65, Black or white, who worked more than 13 weeks last year and three hours last week, not self-employed, not in group quarters, not unpaid family worker, no missing industry or occupation code.

3. The economy-wide racial gap is defined here as the combination between the industries covered in 1938 and the industries covered in 1967.

Alternative, but not incompatible, explanations for the falling wage gap—the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which banned explicit job discrimination, and improvements in education for Black students—may explain part of the decline, but do not address its full magnitude. In all likelihood, civil rights reforms worked in tandem with high minimum wages to produce the biggest episode of racial earnings convergence since World War II. Our research isolates and focuses on the contribution of the 1967 federal minimum wage extension to the narrowing racial earnings gap during the 1960s and 70s.

The 1967 minimum wage reform caused a 6.7% increase in wages.

In 1938, the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) introduced the first federal minimum wage for workers in the manufacturing, transportation and communication, wholesale trade, finance, and real estate sectors. Southern Democrats demanded the exclusion of certain industries because of their high concentrations of Black workers, especially in the South. It was the 1960s civil rights movement that finally pushed President Johnson, a Southern Democrat himself, to extend the minimum wage to additional sectors of the economy under the FLSA of 1966. This introduced the federal minimum wage (as of February 1967) in sectors such as agriculture, hotels, restaurants, schools, hospitals, nursing homes, entertainment, and other services. These sectors employed about 20% of the total U.S. workforce and, critically, nearly a third of all Black workers.

Black workers in the industries affected by the 1967 minimum wage reform saw their wages rise 10% more than Black workers in unaffected industries.

The $1 (in nominal terms) minimum wage introduced in these sectors in 1967 was initially below the federal minimum wage but converged to the level of the federal minimum wage ($1.60) by 1971. As a result, the federal minimum wage was between 40% to 50% of the median wage in the newly covered sectors during the 1970s, a level close to the one seen in the industries that were covered by federal minimum wages in 1938.

How did the 1967 reform affect wages?

We answer this question by comparing the change in wages for workers in sectors covered by the 1967 reform (henceforth referred to as treated industries) to the change in wages for workers in sectors not covered by the reform (control industries) in the years before and after 1967. Prior to the reform in February 1967, annual earnings of workers in the treated versus control industries evolved in parallel, but, starting in 1967, annual earnings increased substantially—by about 5%—for workers in the newly covered industries relative to workers in the control industries. Relative wages continued to increase after 1967 until they peaked in 1971.

Overall, the average wage of workers in the newly covered industries was 6.7% higher relative to the average wage of workers in control industries in 1967–1972 compared to the period before the reform (1961–1966). The same analysis using hourly wage data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics shows similar results: wages in the newly covered industries jump by 8.6% relative to wages in nondurable manufacturing (the control group) after the reform (1967–1969) relative to before.

Another explanation for these findings is alternative shocks happening in 1967 that differentially affect workers in treated versus control industries, such as the Voting Rights Act of 1965. However, in supplementary analyses, we test for similarly timed policy changes that may have occurred in states in the US with high concentrations of industries affected by the 1967 reform, and find that these alternative shocks cannot explain our results.

Wage Effects by Race

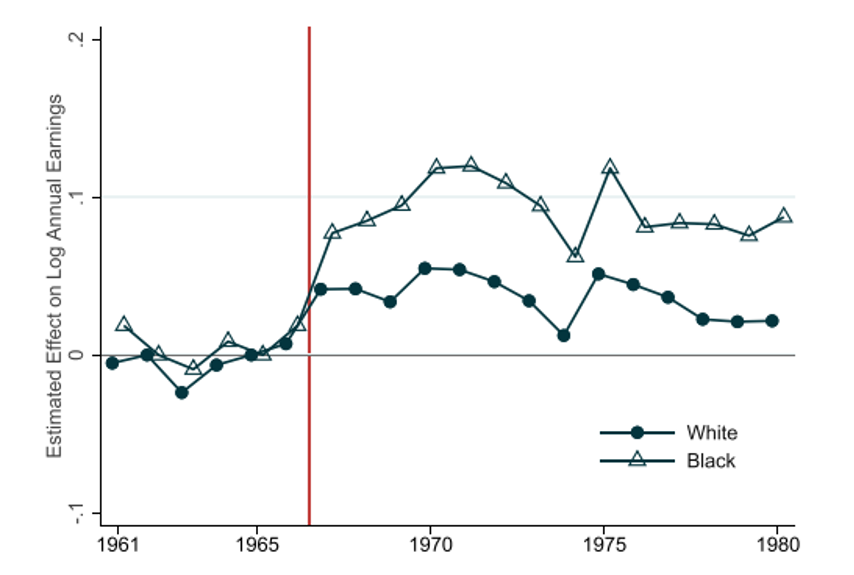

We now turn to our second key finding: the magnitude of the wage response to the 1967 reform was much larger for Black workers (10%) than for white workers (5.5%), as seen in Figure 2. To establish this fact, we compare Black workers in the treated industries to Black workers in the control industries, before versus after 1967, and run the same comparison for white workers.

Figure 2: Heterogeneity in the Wage Effect of the 1967 Reform March CPS 1962–1981

1. Sample: Adults 25–55, Black or white, who worked more than 13 weeks last year and three hours last week, not self-employed, not in group quarters, not unpaid family worker, no missing industry or occupation code.

2. These regressions use a cross-industry design and control for gender, years of schooling, experience, quadratic and cubic in age, full-time/part-time status, number of weeks and hours worked, occupation, and marital status. Includes industry and time fixed effects. Low-education: 11 years of schooling or less. High education: more than 11 years of schooling.

This differential effect on Black workers, in addition to the precise timing of the change in wages, provides additional support that we are picking up the effects of the 1967 reform on the racial wage gap as opposed to, for example, the effects of the 1964 Civil Rights Act. Additionally, by controlling for any state-specific shocks occurring over this period, we can be sure that the wage response does not reflect civil rights era antidiscrimination policies that primarily affected southern states with a large Black population.

Employment Effects

Similar to the wage analysis, we use geographic variation in pre-existing state minimum wage laws to capture the effects of the 1967 increase in the national federal minimum wage on employment. Classical economics theorizes that setting a minimum wage higher than the equilibrium wage will force the labor demand lower than labor supply, creating unemployment. However, we find that there was no detectable change in hours worked following the 1967 minimum wage increase in states that had no minimum wage law as of January 1966 (strongly treated) versus states that did (weakly treated). Nor does the reform affect the probability of being employed versus being unemployed between 1967 and 1972. This finding—that there was no significant change in employment—holds true for both Black and white workers.

To understand the impact on employment of the 1967 coverage extension specifically, we compare the distribution of hourly wages in the newly covered sectors to the predicted distribution that would have occurred under no minimum wage reform.

The minimum wage reform did not have a significant effect on the number of hours worked or probability of being employed for Black or white workers.

Assuming that in the absence of the reform, wages would have evolved according to national income per capita growth between 1966 and 1967, we can estimate the causal impact of the reform on low-wage employment.Take, for instance, laundromats in the south; 40% of the workforce was Black, and the industry experienced a strong shock from the 1967 reform due to the especially low wages and the lack of pre-existing minimum wage laws. After the minimum wage was introduced at $1 in 1967, the data show that excess jobs paying at or slightly above $1 replace missing jobs below $1. Generalizing across 16 industry and region subgroups, there is bunching around the minimum wage, and the difference between excess and missing jobs is close to zero, indicating no disemployment effects.

Even if aggregate employment was unaffected, one concern is that the relative wage gains amongst Black workers as a result of the reform may have prompted employers to hire white workers instead. However, we find no evidence that this type of labor substitution took place, likely due to the entrenched labor norms of the time. Analysis of the 1960s U.S. labor market documents a clear separation of Black and white workers into “back-of-the-house” and “front-of-the-house” jobs, respectively, suggesting that the latter may have been unwilling to take up low status jobs traditionally associated with Black workers.

Racial Earnings Gap

Perhaps the most striking impact of the 1967 minimum wage reform on labor market inequality is the decline in the Black-white earnings gap observed during that era. The reform reduced the gap through two different mechanisms. First, because Black workers were overrepresented in the sectors covered by the minimum wage extension, the increase in the average wage in treated industries reduced the nationwide racial gap.

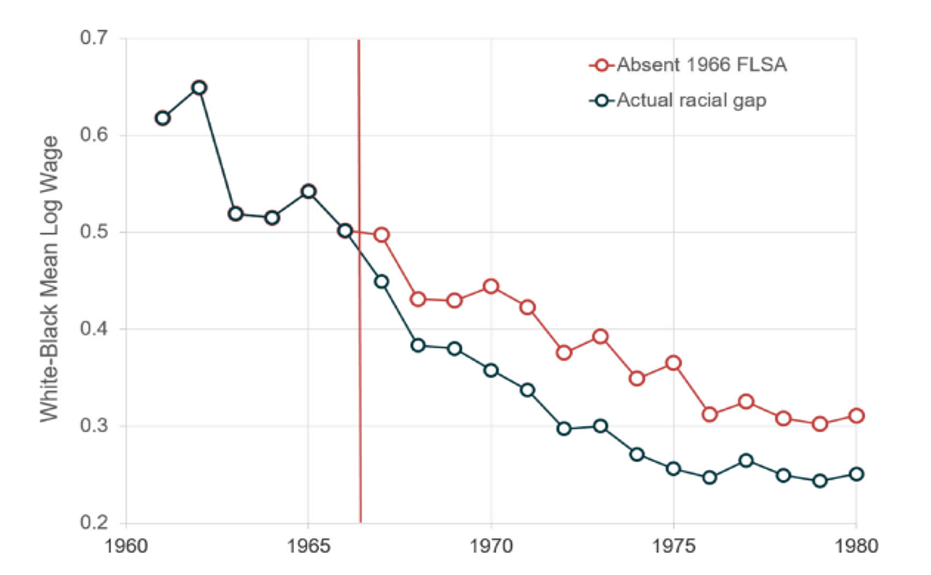

The civil rights era minimum wage extension explains over 20% of the decline in the Black-white earnings gap in the 1960s and 70s.

Second, within the newly covered industries, Black workers were being paid less than white workers prior to the reform, so the wage increase was larger for Black workers than for white workers. Within the treated industries the earnings of Black workers entirely caught up with those of white workers. This second channel accounts for more than 80% of the impact of the reform on the economy-wide racial gap.To estimate the impact of the 1967 reform, we first predicted how the racial earnings gap would have evolved if the minimum wage had not been extended in 1967. To do so, we used information on differences in the share of Black and white workers, and on the racial earnings gap between the control and treated industries. As shown in Figure 3, the 1967 minimum wage extension can explain at least 20% of the decline in the racial earnings gap between 1965 and 1980. This is likely an underestimate since Black workers in the control industries presumably experienced relative earnings gains as a result of the overall increase in the federal minimum wage.

Figure 3: 1967 Reform Reduced Economy-Wide Racial Gap by around 20%

1. March CPS 1962–1981.

2. Sample: Adults 25–55, Black or white, who worked more than 13 weeks last year and three hours last week, not self-employed, not in group quarters, not unpaid family worker, no missing industry or occupation code.

3. The racial gap is calculated as the difference in the average log annual earnings of Black workers and the average log annual earnings of white workers. There is no adjustment for any observables. The CPS collects information on earnings received during the previous calendar year. Therefore, we report estimates of the racial gap, for example, in the 1962 CPS in 1961 above. The economy-wide racial gap is defined here as the combination between the industries covered in 1938 and the industries covered in 1967.

While we focus on the effect of the 1967 extension of the minimum wage to new sectors of the economy, it is likely that the minimum wage affected racial inequality more broadly. To the extent that Black workers were overrepresented at or just below the minimum wage, the minimum wage hikes in 1961, 1963, 1967, and 1968 may have contributed to reducing the racial earnings gap above and beyond the 1967 reform.

Policy Implications

When the March on Washington took place in 1963, Black workers in the United States earned on average 59 cents for every dollar earned by the average white worker. While that number has increased to 78 cents today, improvements have been stagnant since around 1980.

Legislation to raise the minimum wage today would be a universal policy, but it would also be a remarkably effective tool for racial justice.

Our research suggests that raising and expanding the minimum wage today could be central to once again reducing racial inequality without harming the broader market. Congress could expand the minimum wage to cover millions of workers such as restaurant wait staff and gig-work contractors. Establishing federal, state, or local minimum wage thresholds for these sectors, in which workers of color are overrepresented, would improve the often-insufficient take-home pay these workers receive. Though legislation to raise the minimum wage would be a universal policy in name and application, it would also be a remarkably effective tool for racial justice.

This article summarizes ‘Minimum Wages and Racial Inequality’ by Ellora Derenoncourt and Claire Montialoux published in the Quarterly Journal of Economics in 2021.

Ellora Derenoncourt is at Princeton University (Industrial Relations Section) and Claire Montialoux is at the University of California, Berkeley.

Bibliography

Bayer, P. and Charles, K. K. (2018). Divergent Paths: Structural Change, Economic Rank, and the Evolution of Black-White Earnings Differences, 1940-2014. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 133(3):1459–1501.

Chetty, R., Hendren, N., Jones, M. R., and Porter, S. R. (2020). Race and Economic Opportunity in the United States: An Intergenerational Perspective. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 135(2): 711-783.