Summary

A recent wave of high-profile mergers between firms at different points in the supply chain for a common good or service – AT&T and Time Warner, CVS and Aetna, Comcast and NBC Universal, Google and ITA Software – has reinvigorated a long-standing debate on the impact of such vertical integration on consumer welfare and market efficiency. This has potential implications for antitrust enforcement.

A traditional argument in favor of such mergers is that a vertically integrated firm gains cheap access to all inputs produced in-house and this may translate into lower prices for consumers – an outcome of greater efficiency assumed to arise from the elimination of what is known as double marginalization. But building on work by Francis Edgeworth in the 1920s and Michael Salinger in the 1990s, new research shows that when the vertical merger involves a multiproduct firm and a subset of its suppliers, it cannot be assumed that all consumers will benefit.

The study reaches this conclusion by leveraging variation in vertical structure caused by mergers in the US carbonated beverage industry. At least three factors make this industry ideal for such analysis.

First, it is one where multiple upstream and downstream firms interact. Upstream firms such as The Coca-Cola Company or PepsiCo produce concentrate; downstream bottlers purchase concentrate from the upstream firms, mix it with carbonated water, and produce the multiple products that are sold to retailers. Importantly, bottlers purchase concentrate from one or more upstream firms. For example, The Coca-Cola Company’s main bottler bottles both The Coca-Cola Company brands and Dr Pepper Snapple Group brands in many locations across the United States.

Second, a number of vertical transactions took place in 2009 and 2010 involving Coca-Cola, PepsiCo, and some of their bottlers. Because Coca-Cola and PepsiCo merged with only a subset of their bottlers, vertical integration took place in only some parts of the country. This geographical variation in vertical integration generated rich longitudinal and cross-sectional variation in vertical structure, which is key for the analysis.

Third, the transactions that took place in 2009 and 2010 eliminated double marginalization for the brands owned and bottled by Coca-Cola and PepsiCo. But because Dr Pepper Snapple Group remained independent in selling inputs to the bottlers, double marginalization was not eliminated for its brands bottled by the integrated bottlers.

The research provides new evidence of anti-competitive effects of vertical mergers. Vertical integration caused price increases of 1.2-1.5% for Dr Pepper Snapple Group products bottled by vertically integrated bottlers. Vertical integration also caused a decrease of 0.8-1.2% in the prices of Coca-Cola and PepsiCo products bottled by integrated bottlers.

Finally, while vertical integration increased the revenues of Coca-Cola and PepsiCo products, vertical integration decreased the revenues of Dr Pepper Snapple Group products by 1.3% relative to their revenues in areas unaffected by vertical integration. These results are consistent with joint manifestations of efficiency and Edgeworth-Salinger effects of vertical integration.

Main article

A recent wave of high-profile mergers between firms at different points in the supply chain for a common good or service – AT&T and Time Warner, CVS and Aetna, Comcast and NBC Universal, Google and ITA Software – has reinvigorated a long-standing debate on the impact of such vertical integration on consumer welfare and market efficiency. This column reports new research showing that vertical mergers involving multiproduct firms may cause price increases for some consumers in transactions that would typically be viewed as pro-competitive. The findings from the carbonated drinks industry stand in contrast to the common intuition that the elimination of double marginalization with vertical integration is benign.

The competitive impacts of vertical mergers are a long-standing question in antitrust economics. A recent wave of vertical mergers has reinvigorated the academic and policy debate on enforcement, and the discussion is far from settled. An example of this is that US antitrust authorities presented new vertical merger guidelines in 2020, but the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) voted to withdraw these guidelines only a year later.

Central to the competitive analysis of vertical mergers is the notion that they eliminate what is known as double marginalization. This refers to vertical mergers removing the incentive of a supplier to sell inputs to the downstream firm at a price greater than marginal cost. Because inputs and final products are complements, a reduction in the input price decreases the price of the final product, which benefits consumers.

Analysis of the US carbonated beverage industry reveals potential anti-competitive effects of vertical mergers in multiproduct industries

But Salinger (1991), based on ideas in Edgeworth (1925), argues that the elimination of double marginalization may cause price increases when a multiproduct firm integrates with one of its suppliers. Our research explores how that might happen and tests it on data from the US carbonated beverage industry.

How might price rises happen following vertical integration?

Consider a downstream retailer selling two substitute products, A and B, each produced by a different upstream firm. Suppose the retailer vertically integrates with the producer of product A (call it upstream firm A). In that case, vertical integration eliminates the double margin in product A, which has two effects on prices. The first is that the eliminated double margin in product A creates a downward pressure on the price of product A for the reason explained above – that is called the efficiency effect.

The second effect is that the eliminated double margin in product A makes product A cheaper and thus more profitable to sell, creating an incentive to increase the price of product B to sell more of product A. This second effect is a form of foreclosure that we call the Edgeworth-Salinger effect. Salinger (1991) shows that this effect can even cause the prices of both products to increase due to strategic complementarities.

While the elimination of double marginalization with vertical integration is normally characterized as pro-competitive, it may cause anti-competitive price rises

The Edgeworth-Salinger effect is smaller when products A and B are close substitutes. In this case, a small decrease in the price of product A will induce a large decrease in the quantity of product B. In such a case, the downstream firm only needs to decrease the price of product A to sell more of product A.

When instead the products are more distant substitutes, a price increase in product B complements a decrease in the price of product A in getting consumers to purchase more of product A. The effect only holds when the downstream firm sells substitute products. If the products were instead complements, the eliminated double margin in product A would exert downward pressure on the prices of both products.

The Edgeworth-Salinger effect defies the notion that the elimination of double marginalization will necessarily benefit consumers. Hence, questions relevant for vertical merger enforcement are whether this effect is empirically relevant and how its magnitude compares to the efficiency effect of eliminating double marginalization.

Quantifying the Edgeworth-Salinger effect

In practice, quantifying the Edgeworth-Salinger effect is not easy. On the one hand, it is necessary for vertical transactions to change the vertical structure of the industry and to generate cross-sectional variation in exposure to the Edgeworth-Salinger effect.

On the other hand, it is also necessary for these changes not to occur everywhere, because if vertical integration takes place in a specific market, rival firms not involved in the transaction react to it as well. Thus, it is necessary for some markets not to be exposed to vertical integration altogether.

Prices of most Dr Pepper Snapple Group products sold by an integrated bottler rose after vertical integration

We measure the impact of the Edgeworth-Salinger effect on prices by exploiting a series of vertical transactions in the US carbonated beverage industry in 2009 and 2010. We consider transactions that were examined and approved by the FTC subject to remedies in which The Coca-Cola Company and PepsiCo acquired some of their main bottlers in the United States. These transactions are ideal for the examination of the question we address for two reasons.

First, there are many players at the different levels of the carbonated beverage industry. For example, firms like The Coca-Cola Company, PepsiCo, and Dr Pepper Snapple Group produce syrup (or concentrate) that they sell to bottlers, which in turn produce carbonated soft drinks that they sell to downstream customers. Relevant to the question of interest is that bottlers may purchase syrup from more than one upstream producer. For example, at the time of the transactions, some bottlers affiliated with The Coca-Cola Company also produced Dr Pepper products (but not PepsiCo products).

Second, the transactions that we examined involved some but not all of the bottlers that worked with The Coca-Cola Company and PepsiCo. For this reason, and because bottlers in this industry operate within exclusive territories (for example, in each territory there is one, and only one, bottler for The Coca-Cola Company, and one and only one bottler for PepsiCo), vertical integration took place across the United States but not everywhere. Thus, the transactions introduced variation in the vertical structure of the industry not only over time but also across the country. In addition, the transactions introduced variation in the pricing incentives of the integrated bottlers depending on whether they produced Dr Pepper Snapple Group products in their territories.

Data sources

To obtain data that make it possible to observe these changes and to quantify their impact we combine three sources of data that enable us to quantify the Edgeworth-Salinger effect of vertical integration:

- We use scanner data at the product-store-week level from the big data company IRI.

- We combine the scanner data with territory maps of the bottlers involved in the transactions described above.

- We use maps produced by the FTC to identify counties where the integrated bottlers sold Dr Pepper Snapple Group products.

Combining these datasets allows us to measure the impact of vertical integration on the prices of the products of the integrated firms and on the products of Dr Pepper Snapple Group produced by the integrated bottlers.

Price falls of Coca-Cola and PepsiCo products are likely to affect a larger share of consumers than price rises of Dr Pepper Snapple Group products

We estimate the efficiency and Edgeworth-Salinger effects of vertical integration using a ‘differences-in-differences’ research design. To do this, we identify counties that were exposed to vertical integration but not to the Edgeworth-Salinger effect (for example, counties in which the integrated bottler did not sell Dr Pepper products), counties that were exposed to vertical integration and to the Edgeworth-Salinger effect (for example, counties in which the integrated bottler did sell Dr Pepper products), and counties in which none of the bottlers who operated in it vertically integrated (for example, counties served by bottlers not acquired by The Coca-Cola Company or PepsiCo).

An important threat to identification, common to studies of mergers and acquisitions, is that these transactions are, of course, endogenous: The Coca-Cola Company and PepsiCo did not randomly choose which bottlers to integrate with. We argue, however, that this concern is unlikely to be significant in this case for several reasons:

- The bottlers involved in the transactions operated across heterogeneous markets in the United States (for example, high- and low-income markets).

- There were no divestitures of territories after the transactions during our period of analysis. Thus, the integrated companies did not choose to keep specific territories on which to operate but instead kept the territories that the bottlers had before integration.

- We do not observe differential changes in observable characteristics of the locations served by the integrated bottlers relative to those operated by other (non-integrated) bottlers.

Key findings

Our main findings suggest that the prices of Coca-Cola and PepsiCo products sold by integrated bottlers decreased by around 1% following vertical integration, relative to the prices of the same products sold by non-integrated bottlers. At the same time, the prices of Dr Pepper Snapple Group products sold by the integrated bottlers increased by 1.2-1.5% following vertical integration, relative to the price of the same products sold by non-integrated bottlers.

These findings are robust to analyses that take into account first, that the price changes may vary across products with varying popularity; second, the level of aggregation of the data (to consider zone pricing, changes in pricing frequency, and the serial correlation of prices); and third, sub-sample analyses, such as distinguishing between promotional or regular prices, or between local and national retailers, among others.

Revenues of Coca-Cola and PepsiCo products rose by 1.7% and 2.2%, respectively, while revenues of Dr Pepper Snapple Group products fell by 1.3%

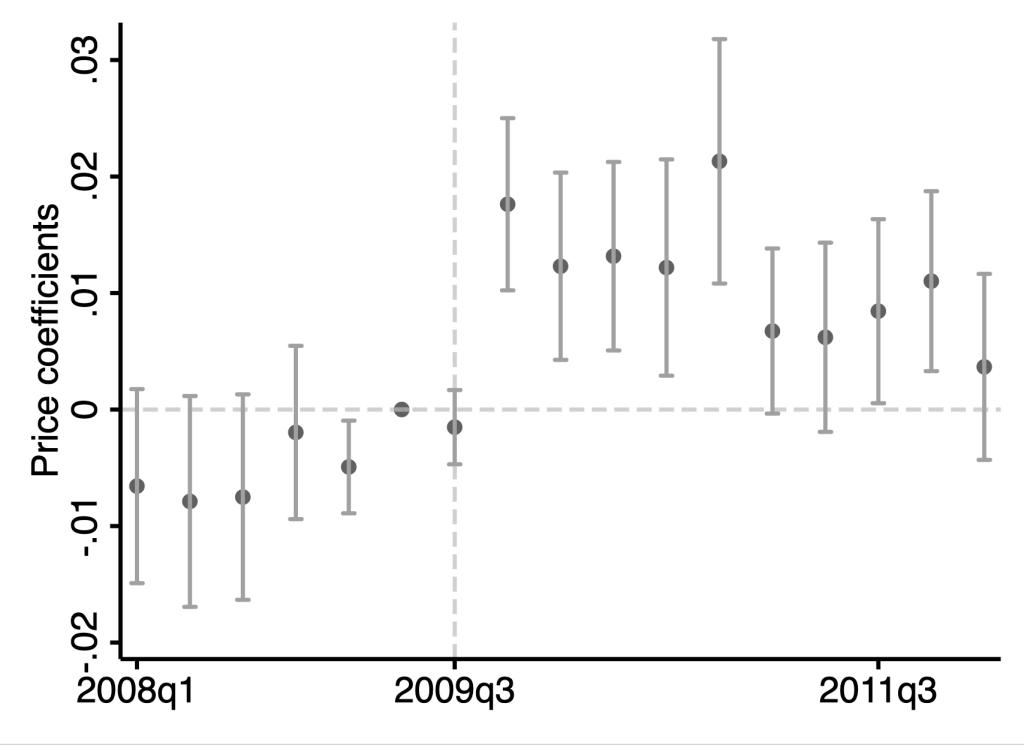

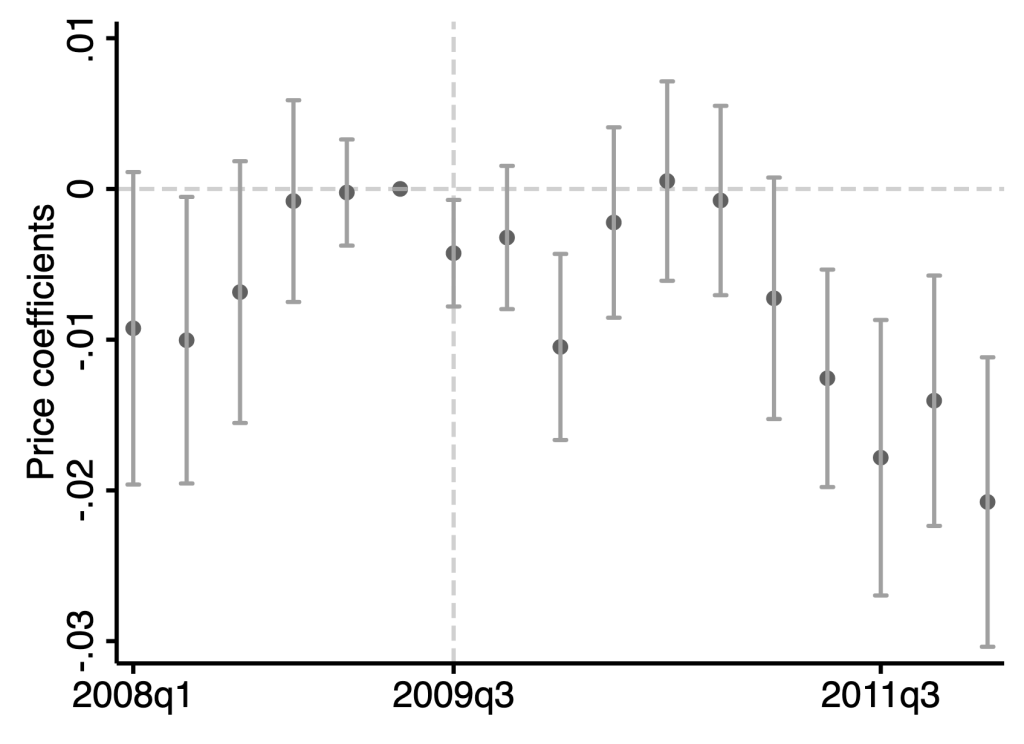

We find that the Edgeworth-Salinger effect manifested quickly: prices of Dr Pepper Snapple Group products produced by integrated bottlers increased from the quarter after vertical integration took place, and these price changes were long-lasting (see Figure 1a). On the other hand, we find that the prices of Coca-Cola and PepsiCo products produced by the integrated bottlers started to decrease only two years after the transactions (see Figure 1b).

Figure 1a

Figure 1b

To examine the implications of these changes, we estimated the impact of vertical integration on product-level prices and quantities, and we aggregated the implied changes in revenues at the firm level. This analysis reveals several important features:

- First, the prices of most Dr Pepper Snapple Group products sold by an integrated bottler increased after vertical integration.

- Second, we see smaller effects on quantities than on prices, which suggest that because of the difference in the popularity of the products of each brand, the decreases in the prices of Coca-Cola and PepsiCo products are likely to affect a larger share of consumers than the increases in the prices of Dr Pepper Snapple Group products produced by integrated bottlers.

- Finally, our revenue analysis shows that the revenues of Coca-Cola and PepsiCo products increased by 1.7% and 2.2%, respectively, while the revenues of Dr Pepper Snapple Group products decreased by 1.3%.

Implications for antitrust enforcement

These findings contribute to the discussion on antitrust enforcement of vertical mergers in at least two ways:

- First, they provide new evidence on how vertical mergers may cause price increases for some consumers. Many recent vertical mergers have involved multiproduct firms, implying that the Edgeworth-Salinger effect is a relevant economic effect to consider when evaluating vertical mergers.

- Second, these findings suggest that the Edgeworth-Salinger effect can be as large as the efficiency effect of the elimination of double marginalization but of the opposite sign, implying that one cannot blindly assume that the elimination of double marginalization will benefit consumers.

This article summarizes ‘The Competitive Impact of Vertical Integration by Multiproduct Firms’ by Fernando Luco (Texas A&M University) and Guillermo Marshall (University of British Columbia), published in the American Economic Review 110(7): 2041-64 in July 2020.