Summary

Young people face a higher risk of unemployment than adults in all countries of the world (ILO 2020), which helps to explain why the World Bank invested $9 billion in 93 skills training programs between 2002 and 2012 (Blattman and Ralston 2015). Despite the popularity of these programs, evidence on the relative effectiveness of vocational training and apprenticeships is limited.

We worked with the NGO BRAC Uganda to randomize applicants for six-month nationwide vocational training scholarships into three groups: those offered vocational training (VT), those offered firm-provided training through apprenticeships (FT), and a control group. VT recipients could select among vocations that were in high demand in Uganda, and received a completion certificate upon completing the VT training. The FT offer involved matching workers to a representative sample of small and medium size enterprises in these same sectors and offering a subsidy to the firm owner to hire and train the worker. No certificate of training was provided in the FT arm.

Take-up rates were significantly higher in the VT arm than the FT arm, due to the limited interest by firms in training apprentices, but we find that the two training tracks resulted in similarly large gains in the sector-specific skills of trainees—an increase of around 0.4 standard deviations over the control group. Therefore, both vocational training and firm-provided training proved effective at generating productive human capital.

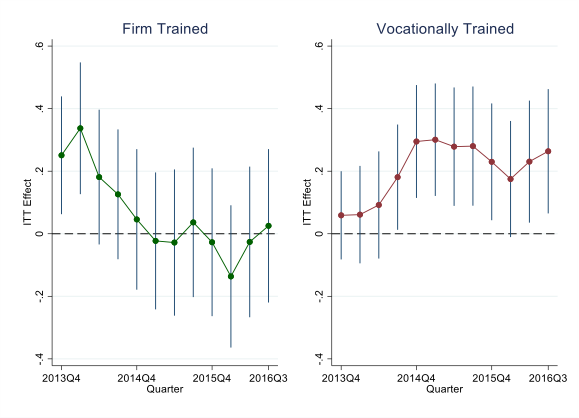

However, exploring the dynamics of impacts over time reveals that labor market gains were short-lived for apprenticeships, but long-lasting for vocational training. Impacts for the FT workers materialized quickly, reflecting the initial placement into firms and the fact that some workers were retained after the end of training. However, these early gains faded over time, and by the end of the follow-up period the employment rates of FT workers looked similar to the control group. On the other hand, the gains for the VT group emerged slowly but were long-lasting, with no sign of decay at the end of the three-year study period.

Using a job ladder model of worker search, we find that differences in the employment dynamics between VT and FT workers are explained primarily by differences in the unemployment-to-job transition rates. When VT workers fell into unemployment, they were able to jump back into employment much faster than other groups. On the other hand, FT workers showed transition probabilities towards the end of the study period that were indistinguishable from the control group. Certification plays a crucial role here. When unemployed, VT workers were able to prove their skills to employers thanks to the certificate; the higher skills of FT workers counted for little while unemployed, however, since they lacked a credible way to signal these skills.

Estimated returns on both FT and VT treatments arms were larger than those in most related studies, due perhaps to our intensive treatments, high-quality partners, choice of sectors with high labor demand, and selection of disadvantaged but highly motivated participants. Overall, vocational training was found to be more cost-effective than apprenticeships at increasing the labor market outcomes of youth. This highlights that human capital alone is not sufficient, and that workers need to have credible means to show their skills to potential employers. Programs targeting both human capital accumulation and skills certification are therefore likely to be most promising.

Main article

Youth unemployment is a significant, and growing, issue in many countries. This randomized study looks to address the limited evidence on the relative effectiveness of vocational training and apprenticeships. It finds that that the two training tracks resulted in similarly large gains in the sector-specific skills of trainees in Uganda, but that labor market gains were short-lived for apprenticeships and longer-lasting for vocational training. A key differentiating factor was that vocational training provided a certificate that workers could use to demonstrate their skills, while apprenticeships did not. Programs targeting both human capital accumulation and skills certification are therefore likely to be most promising.

Motivation: youth unemployment as a global challenge

Young people face a higher risk of unemployment than adults in all countries of the world (ILO 2020). Understanding which active labor market policies are effective at facilitating the transition of youth into remunerative employment is thus critical to ensure global economic and social stability.

Nowhere is the youth unemployment challenge more keenly felt than in sub-Saharan Africa, where over 60% of the population is below the age of 25 and the unemployed are increasing by a million a year, mostly due to youth failing to enter the labor market (UN 2019, ILO 2020). The importance of tackling youth unemployment in sub-Saharan Africa is only going to increase in the coming years, due to the rapid population growth and the economic downturn caused by Covid-19.

In this post, we summarize the results of a field experiment that we conducted in Uganda to evaluate two active labor market interventions commonly used across the developing world to generate skilled employment: (i) in-class vocational training, and (ii) wage subsidies for firms to train workers through on-the-job apprenticeships.

Vocational training vs. Apprenticeships as policy solutions

The World Bank invested $9 billion in 93 skills training programs between 2002 and 2012 (Blattman and Ralston 2015). Despite the popularity of these programs, evidence on the relative effectiveness of vocational training and apprenticeships is limited, especially in the context of developing countries (Card et al. 2017, Blattman and Ralston 2015, McKenzie 2017).

Vocational training and apprenticeships both aim to generate skills and employment but do so by tackling different constraints. In-class vocational training at institutes provides formal training and generally comes with a certificate. However, the effectiveness of this type of training relies on workers being able to find jobs after the end of training. If searching for jobs is costly or firms face significant recruitment costs, then vocational training might not be effective. On-the-job apprenticeships are designed to tackle these search and recruitment constraints by embedding a worker in a firm for training. However, apprenticeship training is typically less formal in nature and is also not certified. Ex-ante it is therefore unclear which model of training can be more effective at increasing youth employment, as this depends on the relative importance of providing formal certified training versus reducing search costs and hiring constraints for firms.

An experiment in the Ugandan labor market

We worked in partnership with the NGO BRAC Uganda. In 2012, BRAC advertised vocational training scholarships across the country. To be eligible to apply, individuals had to be below the age of 25, out of school, and economically disadvantaged. A higher number of eligible youth applied than there were scholarships available. Therefore, we exploited an oversubscription design to randomize applicants into three groups: a first group was offered vocational training (VT), a second group was offered firm-provided training through apprenticeships (FT), and a third group was held as control.

The VT offer included a scholarship to attend six months of training at a partner vocational institute. The training was sector-specific, and workers could select among vocations that are in high demand in Uganda, such as motor mechanics or hairdressing. Workers received a certificate upon completing the training. The FT offer involved matching workers to a representative sample of small and medium size enterprises in these same sectors and offering a subsidy to the firm owner to hire and train the worker for six months. Those owners interested in taking on the worker entered into a contract with BRAC to provide sector-specific on-the-job training. No certificate of training was provided in the FT arm. BRAC conducted extensive monitoring of the training activities at both the institutes and the firms.

The baseline survey and randomization took place in 2012 and the training programs in 2013. We then followed up with the workers yearly for three years after the end of training.

Differences in take-up between the two programs

Take-up rates differed significantly across the VT and FT groups. Over two thirds of workers in the VT group started the training. However, only a quarter of workers in the FT group started an apprenticeship. This was due to the limited interest by firms in taking on a worker, as training involved substantial time costs for firm owners. In line with this, more profitable firms with a higher opportunity cost of time were less likely to take on a worker. On the other hand, worker characteristics do not predict take-up in the FT arm, and conditional on receiving an offer to start training at a firm, workers in the FT arm were as likely to start as those in the VT arm.

This differential take-up is important in two ways. First, it highlights one challenge with implementing firm-training interventions: their effectiveness crucially depends on the ability of firms to take on workers for training. This challenge does not arise with training institutes as training workers is their core business. Second, since the lower take-up in the FT group is driven by firm rather than worker characteristics, we can still compare the workers who started VT with those who started FT. That is, our analysis of the “compliers” in the two interventions is still valid since the two groups are similar.

Both programs resulted in substantial gains in sector-specific skills

In the follow-up surveys we tested the skills of workers in all treatment arms. We did so through a written sector-specific skills test, which we designed in collaboration with vocational trainers and firm owners to ensure that it captured skills learned through either type of training. We find that the two training tracks resulted in similarly large gains in the sector-specific skills of trainees, corresponding to an increase of around 0.4 standard deviations over the control group. Therefore, both vocational training and firm-provided training proved effective at generating productive human capital.

Labor market gains were short-lived for apprenticeships, but long-lasting for vocational training

When averaged over the three years post intervention, both VT and FT resulted in positive and significant impacts on labor market outcomes. Workers in the FT group experienced a 14% increase in the probability of employment over the control group, and workers in VT experienced a 20% increase. These impacts are not statistically different between the two groups. We find similarly positive impacts on an index of labor market success combining several indicators including earnings. Focusing on those workers who took up training (i.e., the compliers) does not change our key conclusion that the average impacts were similar across the two groups.

However, exploring the dynamics of impacts over time reveals a striking finding: gains were short-lived for the FT group but were long-lasting for the VT group. Impacts for the FT workers materialized quickly, reflecting the initial placement into firms and the fact that some workers were retained after the end of training. However, these early gains faded over time, and by the end of the follow-up period the employment rates of FT workers looked similar to the control group. On the other hand, the gains for the VT group emerged slowly but were long-lasting, with no sign of decay at the end of the study period. These dynamics, shown in Figure 1, reveal that the effects averaged over the post-intervention period hide a remarkable reversal of fortune between workers in the two tracks. We find similar dynamics when looking at total earnings.

When looking instead at wages conditional on employment, we find that impacts were positive and similar across VT and FT workers throughout the post-intervention period. This is consistent with the positive impacts on skills accumulation documented in both tracks. That is, when FT workers managed to find jobs, their earnings were similar to those of VT workers, since their skills were similar. The main difference between the two tracks over time appears to be instead in the extensive margin of employment probability.

Figure 1: Impacts on number of months worked per quarter

–

Mechanisms: the role of labor market mobility

To explore the mechanisms leading to this reversal of fortune between VT and FT workers, we estimated a job ladder model of worker search. Workers in the model differ in two dimensions that are allowed to be affected by the treatments. First, they differ in terms of productivity. Second, they differ in terms of labor market mobility, summarized by (i) unemployment-to-job, (ii) job-to-job, and (iii) job-to-unemployment transitions. We use the model to study the importance of these channels in accounting for the differences in dynamics across the two training tracks.

We estimate the model using our data on worker skills and on the monthly labor market histories of workers in the follow-up period, where for every month we know the employment status of workers, their earnings, and their labor market transitions.

The model estimates reveal one key finding: differences in the employment dynamics between VT and FT workers are explained primarily by differences in the unemployment-to-job transition rates. This means that when VT workers fell into unemployment, they were able to jump back into employment much faster than FT workers and the controls. On the other hand, FT workers showed transition probabilities towards the end of the study period that were indistinguishable from the control group. That is, once FT workers became unemployed, they were no more able than control workers to find a new job. Over time, this then led the employment rates of FT workers to converge back to the control group as they lost their initial jobs.

The fact that only the skills of VT workers were certified can explain these results. When unemployed, VT workers were able to prove their skills to employers thanks to the certificate; on the other hand, the higher skills of FT workers counted for little while unemployed, since they lacked a credible way to signal these to the market. This result is in line with the findings of a growing literature on information frictions in developing countries, which shows that screening costs impede the efficient matching of workers and firms (Abebe et al. 2020, Bassi and Nansamba 2021, Carranza et al. 2020).

Policy implications

Overall, vocational training was found to be more cost-effective than apprenticeships at increasing the labor market outcomes of youth. This is particularly true if we take into account the lower take-up rate in the FT group, driven by the limited interest of firms in training apprentices.

The cost of both vocational training and apprenticeships was orders of magnitude higher than the monthly earnings of the average worker in our sample at baseline. This suggests that both interventions generated impacts by helping workers overcome credit constraints.

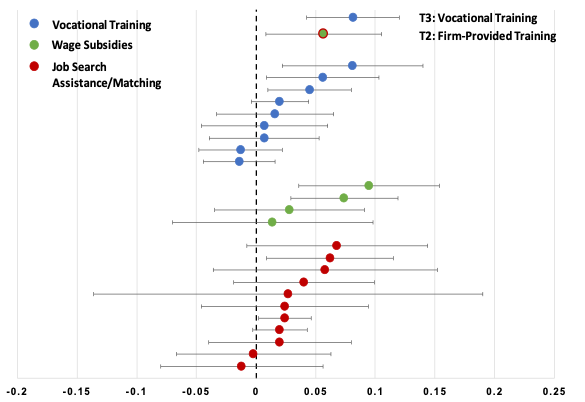

As shown in Figure 2, our estimated returns to training are larger than those in most related studies. We highlight four potential reasons for this, which can inform the design of training interventions in other contexts. First, our treatments were intensive: training lasted six months and was a full-time activity for workers. Second, we partnered with high-quality and reputable vocational institutes. Third, we offered training in a limited number of sectors with substantial labor demand. Finally, the workers participating in the study were economically disadvantaged but highly motivated to get trained and to work.

Figure 2: Comparison of treatment effects on employment with other studies

–

Our results provide new insights on the importance of investing in human capital to tackle youth unemployment. They also highlight that human capital alone is not sufficient, however. Making sure that workers have credible means to show their skills to potential employers is essential to fully reap the benefits of the human capital investment and ensure that youth can transition to productive employment. Therefore, programs targeting both human capital accumulation and skills certification are likely to be most promising.

This article summarizes ‘Tackling Youth Unemployment: Evidence from a Labor Market Experiment in Uganda’ by Livia Alfonsi, Oriana Bandiera, Vittorio Bassi, Robin Burgess, Imran Rasul, Munshi Sulaiman, and Anna Vitali. The article was published in Econometrica in 2020.

Livia Alfonsi is at the University of California, Berkeley, Oriana Bandiera is at the London School of Economics, Vittorio Bassi is at the University of Southern California, Robin Burgess is at the London School of Economics, Imran Rasul is at University College London, Munshi Sulaiman is at BRAC, and Anna Vitali is at University College London.