Summary

In most trade frameworks, transient shocks like financial crises can only have temporary effects. Yet models with multiple equilibria stress that large shocks can permanently shift an economy from one equilibrium to another. It can be empirically difficult to establish the long-run effect of financial shocks on the patterns of global trade. This difficulty is both because economic fundamentals affect exports and banking sector health simultaneously, and because data on exogenous shocks are usually limited to short-run outcomes within one country or require combining dissimilar episodes.

The 1866 London banking crisis presents a unique opportunity to overcome these challenges as it disrupted short-term bank-intermediated financing in almost every country in the world. The crisis—which was caused by the unanticipated bankruptcy of a prestigious interbank lender in the City of London—propagated from London around the world to varying degrees based on the network of British banks.

Results show that the financing shock immediately lowers exports volumes on the intensive margin. Countries exposed to a one standard deviation increase in bank failures have 8.5% lower exports one year later. On the extensive margin, exporters more exposed to the shock have fewer trade partners afterwards and are less likely to engage in international trade at all. These export losses are highly persistent in the long run, both in the aggregate of total exports and in terms of exporter market shares within destinations. Importers bought on average 18% less each year from exporters with a one standard deviation higher exposure to bank failures after the crisis, with effects significantly different from zero persisting for four decades.

The evidence suggests that trade patterns changed in a manner consistent with the financing shock affecting countries’ costs of exporting, likely through a trade financing channel. Exporters that were likely to provide similar goods benefited when their competitors were exposed to the shock. In addition, exporters whose exposure to bank failures were likely to be dampened by access to alternative sources of financing during the shock had lower losses, and relationships that relied less on trade finance experienced less persistent losses.

The empirical finding of persistence motivates a conceptual framework featuring sunk costs of establishing relationships and substitutability across exporters. The framework predicts long-run market share losses for exporters as a result of importers expanding their trade relationships on the extensive margin once the financing shock raises their existing exporters’ prices.

This prediction has important implications for international trade today. First, any shock to the relative price of exports—including, for example, a sharp tariff change—could disrupt trade patterns. Second, changes in trade patterns are driven by importers trading off the costs of establishing a new relationship with the benefits of sourcing cheaper goods. Disruptive effects are therefore likely to be smaller where goods exhibit a low degree of substitutability and may be particularly large during periods of rapid growth when relationships are being established.

Main article

What are the long-run effects of financial shocks on patterns of global trade? The 1866 London banking crisis presents a unique opportunity to overcome the empirical difficulties in answering this question. The financing shock at the root of the crisis led to immediate and persistent export losses for affected countries. Trade patterns changed in a manner consistent with the financial shock affecting countries’ cost of exporting. These findings indicate that shocks to the relative price of exports could disrupt trade patterns, and that disruptions are driven by importers trading off the costs of establishing a new relationship with the benefits of sourcing cheaper goods.

International trade patterns are highly stable and understood to be shaped by slow-moving forces of comparative advantage such as differences in technologies, endowments, and institutions. In most trade frameworks, transient shocks like financial crises can only have temporary effects. Yet models with multiple equilibria stress that large shocks can dislodge the economy from a given equilibrium and leave it permanently in a different one. In addition, financial crises are a consistent feature of both emerging and developed markets. It therefore remains a policy-relevant empirical question whether and for how long these crises affect the patterns of international trade.

In my recent article, “Reshaping global trade: The immediate and long-run impact of bank failures,” published in the Quarterly Journal of Economics in 2022, I use the historical setting of the largest banking crisis in British history—the crisis of 1866—to show that a large financial shock can have a decades-long impact on the patterns of international trade.

Establishing the long-run effect of financial shocks on the patterns of global trade is important, but difficult.

Establishing the long-run effect of financial shocks on the patterns of global trade is difficult for multiple reasons. First, economic fundamentals affect exports and banking sector health simultaneously. Second, even when it is possible to isolate an exogenous shock to the financial sector, data are usually limited to short-run outcomes within one country or require combining episodes from institutionally dissimilar countries and time periods. Ideally, one would be able to trace the long arm of history over uninterrupted decades in a setting where all countries are exposed to the same shock to their financial institutions.

The 1866 London banking crisis presents a unique opportunity to overcome these challenges. The crisis originated in London, but it disrupted short-term bank-intermediated financing in almost every country in the world. At the time, Britain was the center of the global financial system: British banks were the dominant providers of short-term credit and operated in countries that accounted for 98% of the value of world exports. The crisis propagated from London around the world to varying degrees based on the network of British banks. This variation in the intensity of the shock allows me to compare exports volumes across locations that were more or less exposed to British bank failures, before and after 1866.

Historical and institutional context:

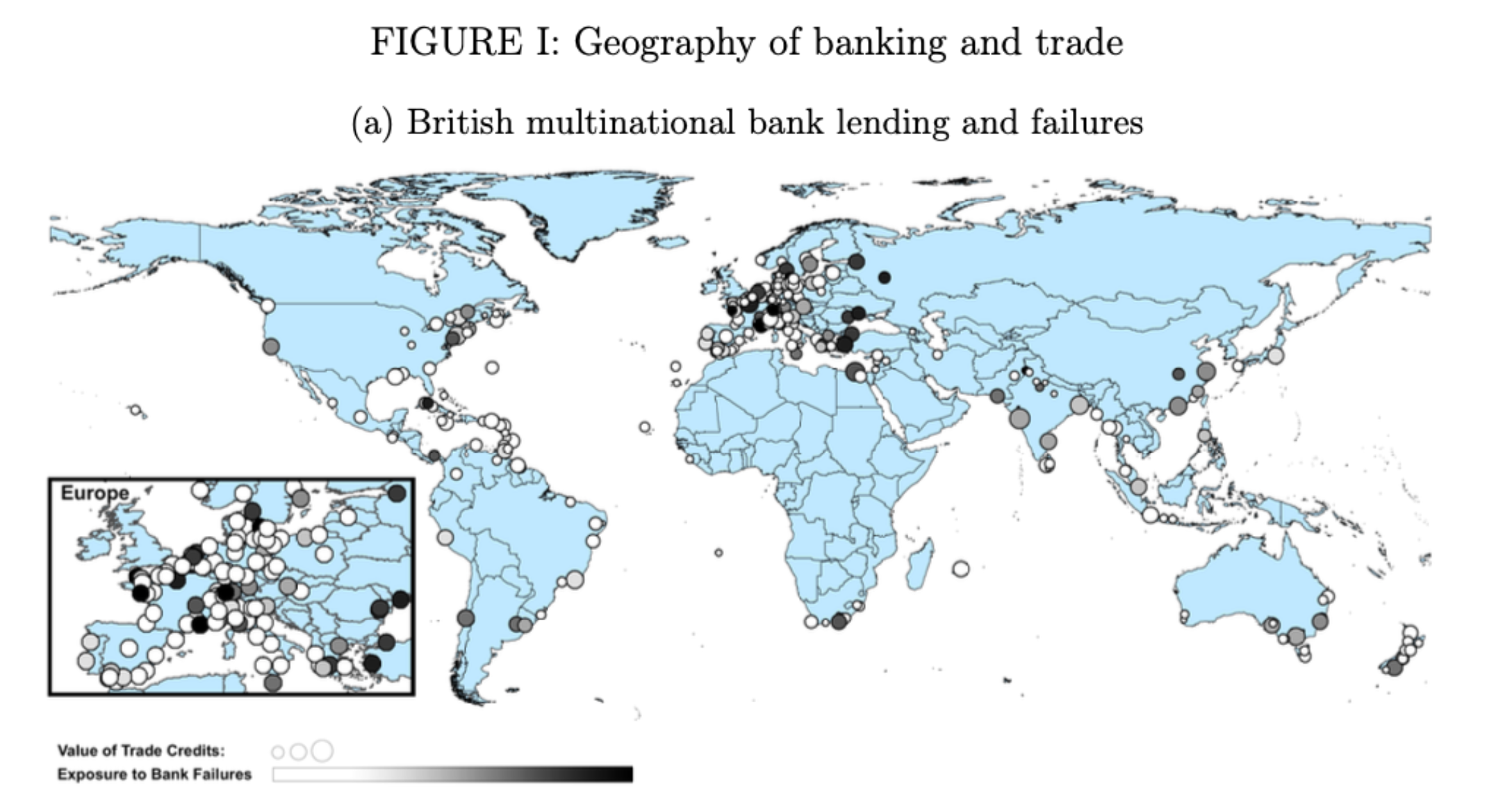

Contractual and information frictions were a costly barrier to establishing trading relationships in the 19th century, as they are today. The long lag between the initial shipment by exporters, the receipt of goods by importers, and their final sale to consumers means that purchase and payment is staggered, and there is room for default on both sides. Banks were well positioned to overcome these frictions because they operated locally, which gave them superior knowledge of an exporting firm’s risk and allowed them to take collateral, often in the form of goods shipped. In the 19th century, British banks were able to profitably lend to foreign exporters through their overseas offices in a business model that allowed them to benefit from access to the deepest capital market in the world in London. These structural advantages stemming from the London connection contributed to British banking dominance and global reach such that by 1865 these banks operated in almost every country and well beyond the British empire (Figure 1).

The 1866 British banking crisis shows that a financial shock can have a decades-long impact on international trade patterns.

The 1866 crisis was caused by the unanticipated bankruptcy of the firm Overend & Gurney, the largest and most prestigious interbank lender in the City of London. Its business as an intermediary was restricted to the safe business of buying and selling liquid, short-term bills of exchange from and to London banks. It did not lend long-term on illiquid assets, and it had no overseas operations. It also did not finance trade and had no exposure to overseas exports markets. However, its failure caused a run on the banks headquartered in London, which caused 21 out of 128 multinational banks to fail. Headquarter closures caused branches abroad to close immediately since they relied on the capital from London.

I capture the importance of each bank to the financing of exports in global markets by hand collecting the loans that had been granted by these banks in cities around the world right before the crisis. I then measure each export market’s exposure to bank failures in London using this credit information.

Notes: Figure 1a maps the distribution of the city-level exposure to bank failures. The size of the points denotes the log value of total credit at each city and the color gradient denotes the exposure to failure, ranging from 0 to 1.

Main findings:

My first set of results shows that the financing shock immediately lowers exports volumes on the intensive margin. Countries exposed to a one standard deviation increase in bank failures have 8.5% lower exports one year later. These results are robust to alternative specifications, count regression methods, and subsample restrictions. On the extensive margin, exporters more exposed to the shock have fewer trade partners afterwards and are less likely to engage in international trade at all. These differences are due to a lower propensity to start trading as opposed to an increase in the likelihood of stopping.

The crisis propagated from London around the world to varying degrees based on the network of British banks.

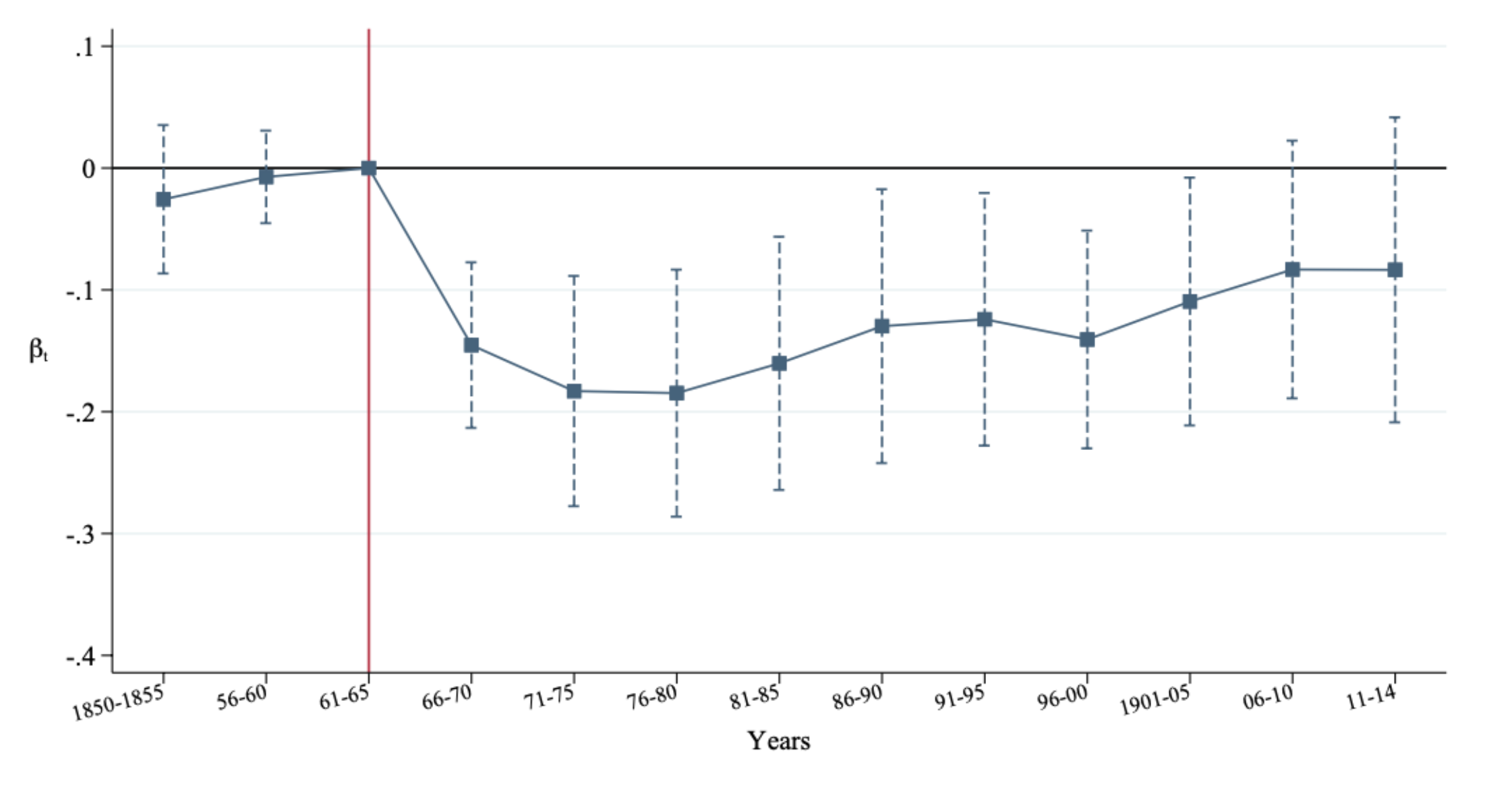

My second set of results shows that the export losses are highly persistent in the long run, both in the aggregate of total exports and in terms of exporter market shares within destinations (Figure 2). In the baseline estimation, importers bought on average 18% less each year from exporters with a one standard deviation higher exposure to bank failures after the crisis, with effects significantly different from zero persisting for four decades. There is little recovery, and the estimated hysteresis is robust to controlling for a wide variety of contemporary shocks and initial macro-economic conditions. These effects are robust to accounting for country-level demand shocks and a host of measures of resistance to trade between countries. Simulated placebo shocks also fail to recreate these patterns.

Figure 2: The impact of exposure to the 1866 bank failure on the average exporter’s market share

Notes: Figure 2 plots the point estimates and 95% confidence intervals of the impact of exposure to bank failures in a country to the value of that country’s exports to the average destination each year. Point estimates and standard errors are scaled by the mean of treatment so the magnitudes can be interpreted as the effect for the average exporter.

Role of finance:

I provide empirical evidence that trade patterns changed in a manner consistent with the financing shock affecting countries’ costs of exporting, through a trade financing channel. First, exporters that were likely to provide similar goods benefited when their competitors were exposed to the shock. This effect is true both across countries (where countries in the same geographical region produce and export similar bundles of goods) and within countries (where ports in the same country ship similar bundles of goods). In both cases, after controlling for a country or port’s own exposure to bank failures, the average exposure of their neighboring competitors positively benefits their own exports.

Countries exposed to a one standard deviation increase in bank failures have 8.5% lower exports one year later.

Second, exporters whose exposure to bank failures were likely to be dampened by access to alternative sources of financing during the shock had lower losses. Third, relationships that likely relied less on trade finance, such as those that were physically closer, experience less persistent losses than more distant relationships.

In addition, I find no impact of exposure to bank failures on countries’ imports. This corroborates the evidence that these international banks were primarily financing exporting activity—the supply side of trade—but had no role in financing consumption. Therefore, unlike in 2008-9, the relative reduction in trade did not appear to be driven by demand but was rather a supply shock.

Mechanisms for persistent effects:

The empirical finding of persistence motivates a conceptual framework featuring sunk costs of establishing relationships and substitutability across exporters. The main assumptions of the framework follow from the details of the institutional context that features highly substitutable goods (commodities trade), high sunk costs (slow communication), and intense competition (rapidly expanding trade networks in the 1860s and 70s). The framework predicts long-run market share losses for exporters, even holding demand constant. These effects come from importers expanding their trade relationships on the extensive margin once the financing shock raises their existing exporters’ prices.

Export losses related to the financial shock are highly persistent, with effects evident for four decades.

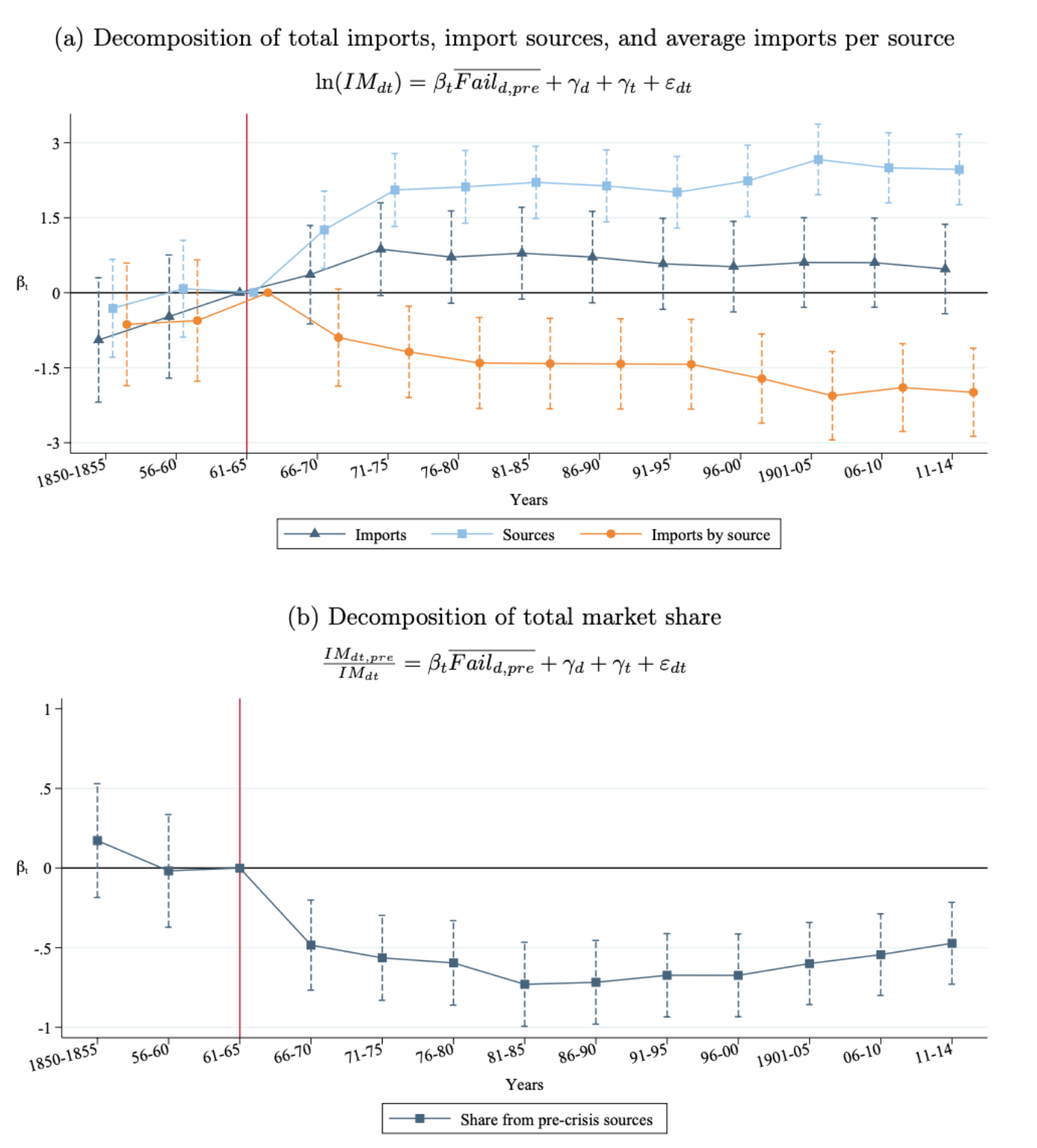

Empirically, I show that importers whose trade partners were more exposed to the shock formed more new relationships, resulting in a lower share of their total imports coming from pre-existing relationships. While importers sourced less from each country on average, there is significant heterogeneity in the exporters that lost market share. A second decomposition of the aggregate imports into the share of total imports between new trade partners formed after the shock versus pre-existing trade partners shows that the pre-existing relationships with high exposure experience a sharp decline in total market share (Figure 3). This market share decomposition has the same overall pattern as the market share losses in the baseline estimation.

Figure 3: Decomposition of effect of indirect exposure on importers

Notes: Figure 3a plots the point estimates and 95 percent confidence intervals for three separately estimated regressions of the relationship between an importer’s volumes of trade and its exporters’ exposure to the crisis. The dependent variable is the log of total imports (dark blue triangle), the log of number of trade partners (light blue square), and the log of average imports per source (orange circle). This decomposition illustrates the substitution on the extensive margin (light blue squares) that is counteracting the overall average drop in import volumes on the intensive margin (orange circles) such that overall purchase volumes (dark blue triangles) are unaffected.

Figure 3b has the share of total imports from pre-crisis trade partners as the dependent variable. This plot shows that the share of overall purchase from pre-crisis trade partners is significantly lower if those partners were more exposed to the crisis.

Policy implications:

Financial sector shocks are a common occurrence, and they are known to disrupt real economic activity in the short term. This article shows that in certain sectors that are particularly sensitive to financial frictions, like international trade, these disruptions can have persistent effects. These persistent effects can be understood within a framework where establishing trade relationships entail significant sunk costs. Exporters exposed to the financial shock at a period when the world was on the cusp of a major expansion in globalization were disadvantaged relative to their competitors, leading them to have persistently lower market shares.

The framework predicts long-run market share losses for exporters as importers react to higher prices by building new relationships.

Extrapolating from this historical study to the implications for international trade today, there are several factors that are relevant. First, while the disruptions discussed here were due to a banking crisis, any shock to the relative price of exports, such as those stemming from a sharp tariff change, could also disrupt the patterns of trade. Second, changes in trade patterns are driven by importers trading off the costs of establishing a new relationship with the benefits of sourcing cheaper goods. If the goods are less substitutable, it would be difficult for importers to pursue this strategy, and the disruptive effects would be smaller. Since a large fraction of modern international trade is in very specific and less substitutable products, shocks would be less likely to have large and persistent effects. However, these disruptions could be particularly costly during times when relationships are being established, including periods of rapid growth and expansion of trade networks.

This article summarizes ‘Reshaping Global Trade: The Immediate and Long-Term Effects of Bank Failures’ by Chenzi Xu, published in The Quarterly Journal of Economics in November 2022.

Chenzi Xu is at the Stanford University Graduate School of Business, and is affiliated with NBER, CEPR, SIEPR, and the King Center. She is an Associate Editor at the Journal of Political Economy.