Summary

Francis Bacon coined the famous phrase “knowledge is power.” This simple idea is used to champion pay transparency to empower women and minority workers. In a recent paper, however, we show that while inequality falls as the rate of pay transparency increases, so do average wages.

What is the mechanism behind this counter-intuitive result? Consider a worker who demands a pay raise. Without pay transparency, the firm may be willing to meet this worker’s demand, fearing they would lose the worker otherwise. However, with pay transparency, the firm may not, knowing that they’d have to give everyone else a raise too. Transparency effectively transfers bargaining power to the employer through a credible commitment to set wages lower.

We formalize this intuition in a model of dynamic bargaining between a firm and many workers. In our model, the firm knows how much it values labor and commits to a maximum wage it is willing to pay for a particular job. Prospective employees propose different take-it-or-leave-it job offers to the firm. If they knew with confidence the maximum the firm is willing to pay for their labor, they would all ask for exactly that amount, but they have incomplete information. In our model, transparency is the rate at which workers learn about this maximum wage. If there is no pay transparency, the firm optimally accepts the wage request of any worker so long as it is below its true value of labor. If there is high pay transparency, workers quickly learn about the high pay of their coworkers and demand the same, knowing it’s still in the firm’s interest to accept. Anticipating information sharing, the firm sets a maximum wage lower than the value of labor to maintain profitability. In the context of our model, therefore, workers receive higher average wages under pay secrecy but there is more wage inequality among employed workers.

To test the predictions of this model, we use data from 13 US states who passed pay transparency laws protecting the “right of workers to talk” (ROWTT) about wages prior to federal policies extending these rights to all government contract workers in 2016. Using a multi-period difference-in-differences (“event study”) design, we find that ROWTT laws decrease the average wages of full-time workers by roughly 2% over the three years following enactment.

The size of this effect is mediated by the degree of individual bargaining power that workers have before the enactment of these laws. We find a negligible impact on the wages of unionized occupations and a bigger impact on wages of college-educated workers with higher individual bargaining power, whose wages decline on average by 4%.

One interpretation of our results that we wish to guard against is that information about pay is necessarily bad for workers. The form of pay transparency we study is internal to the firm: wages are observable only to already-employed workers. By contrast, if cross-firm wage sources are available to all workers, information spillovers between coworkers will have a muted impact on worker knowledge and pay policies of the firm. As a result, renegotiations induced by cross-firm transparency could increase wages. Cross-firm transparency may also lead firms to intensify their wage competition.

Main article

Pay transparency is often touted an effective mechanism to empower women and minority workers. Revealing pay disparities within a firm has merits, equalizing pay and closing the gender wage gap. Our research shows, however, that it can also lead to lower average wages as it transfers bargaining power to the employer, who can make a credible commitment to set wages lower. Lower wages stem from internal spillovers between negotiations. Transparency policies that avoid these spillovers, such as publicizing salaries across firms, may have different equilibrium effects, potentially providing the knowledge that empowers workers rather than employers.

Francis Bacon coined the famous phrase “knowledge is power.” This simple idea is used to champion pay transparency to empower women and minority workers. Advocates argue that workers don’t know what their employer is willing to pay, and more information about coworker pay allows for renegotiations, which raise up and equalize wages, especially those of underpaid workers. Thirteen US states passed pay transparency laws protecting the “right of workers to talk” (ROWTT) about wages prior to federal policies extending these rights to all government contract workers in 2016. At least a dozen more states have passed additional pay transparency legislation since. Our research shows that these pay transparency laws have counterintuitively reduced worker bargaining power, and—in the process of achieving more equal pay—lowered wages.

Revealing pay disparities within a firm has merits, equalizing pay and closing the gender wage gap.

To understand the mechanism behind this counter-intuitive result, consider a worker who demands a pay raise. This could be due to the worker having (or receiving) a high wage offer from another employer and deciding to “push the envelope” in a negotiation. Without pay transparency, the firm may be willing to meet this worker’s demand, fearing they would lose the worker otherwise. However, with pay transparency, the firm may not. The firms might instead respond by saying: “If I give you a higher salary, I’ll have to give everyone else a raise too, and I just can’t afford that.” In other words, transparency stiffens the backbone of the firm in wage negotiations. Realizing that the firm will credibly walk away from a high wage offer, the worker tempers her demands, and is less willing to “push the envelope.” In effect, pay transparency lowers the de facto bargaining power of this worker, and enforces a low wage.

We formalize this intuition in a model of dynamic bargaining between a firm and many workers, and then test the predictions of this model using the roll-out of US state pay transparency mandates between 2004 and 2016.

Pay transparency laws have counterintuitively reduced worker bargaining power, and—in the process of achieving more equal pay—lowered wages.

Modelling the effects of pay transparency

Our model contributes to our understanding of what happens when workers do not perfectly know their employer’s value for labor, but learn about it through information about coworkers’ pay negotiations. In our model, the firm knows how much it values labor and commits to a maximum wage it is willing to pay for a particular job. Workers face different opportunities in the labor market; some may face discrimination, or differences in professional networks or ability to relocate for other job opportunities. Thus, in their initial negotiation with the employer, they propose different take-it-or-leave-it job offers to the firm. Workers want to earn a premium over their best outside alternative but know that making too high an offer runs the risk of losing the employment opportunity. If they knew with confidence the maximum the firm is willing to pay for their labor, they would all ask for exactly that amount, but they don’t know this maximum without observing what the firm has been willing to pay others. In other words, the workers have incomplete information about the value of the firm. Transparency is the rate at which workers learn about the wages of their peers, and therefore, about the maximum wage the firm is willing to pay.

If there is no pay transparency, workers never receive new information that would precipitate a renegotiation. Thus, differences between what workers initially bargained for persist. Because the firm is not concerned about workers sharing pay information, it optimally accepts the wage request of any worker so long as it is below its true value of labor, employing all workers it can hire without making a loss.

In effect, pay transparency lowers the de facto bargaining power of a worker, and enforces a low wage.

If there is high pay transparency, workers learn the pay of their coworkers when they set foot in the workplace. When a worker observes a high wage earned by one of her coworkers, she knows she can demand the same high wage and it’s still in the firm’s best interest to accept it rather than lose her. Anticipating information sharing, the firm sets a maximum wage lower than the value of labor to maintain profitability. On the flip side of the negotiating table, each worker’s initial demand is exactly equal to her outside option—there is no reason to ask for a premium and risk being rejected given that she can immediately renegotiate after observing peer wages. Taken together, these responses imply that each worker receives the maximum wage chosen by the firm upon being employed as long as that maximum wage is preferred by the worker over their outside opportunity. In other words, high pay transparency is equivalent to firm wage posting.

Classic results from auction theory imply that it is better to be the party making a posted take-it-or-leave-it wage offer than to be the party receiving the offer (Williams, 1987). In the context of our model, workers receive higher average wages under pay secrecy but there is more wage inequality among employed workers. Our model generalizes this notion: as the rate of pay transparency increases, inequality and wages both fall. In labor markets where workers have less individual bargaining power to begin with, such as in unionized positions where workers bargain collectively, transparency will have a muted impact on the spillovers between negotiations and thus a smaller impact on wages. In labor markets where workers have more individual bargaining power, such as among highly educated workers in non-unionized jobs, the impact on wages will be larger and more negative.

In labor markets where workers have less individual bargaining power to begin with, such as in unionized positions, transparency will have a more muted impact.

The real-world effects of pay transparency in the US

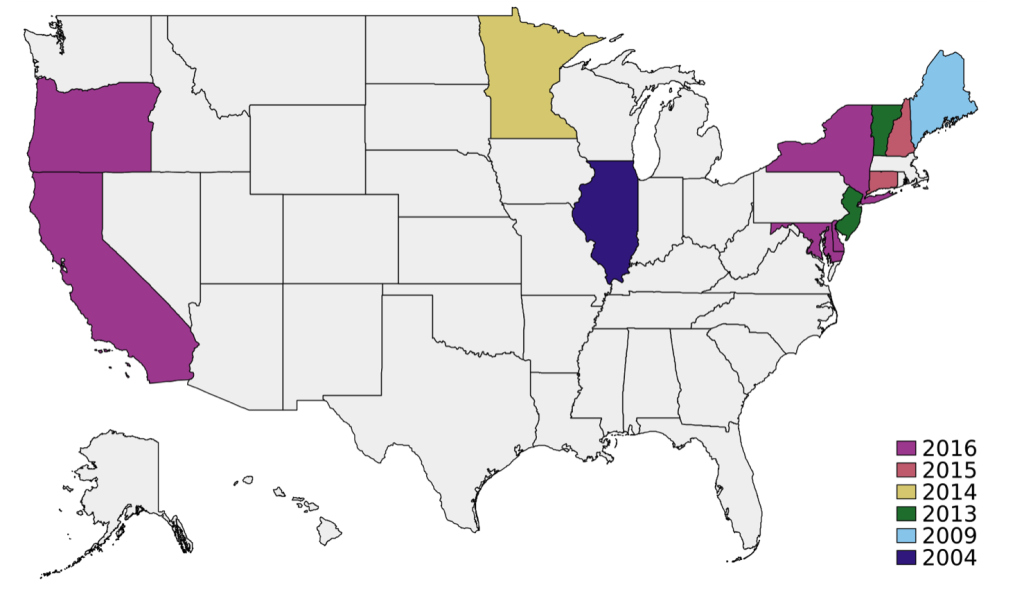

We test the prediction that pay transparency lowers wages by studying the evolution of wages in the US following the enactment of ROWTT laws. Between 2004 and 2016, 13 states enacted legislation that promotes the sharing of pay information between coworkers by harshly punishing employers who try to intervene or intimidate workers to prevent them from sharing or inquiring about pay (Figure I).

Figure I: Year Right of Workers to Talk (ROWTT) Law Takes Effect

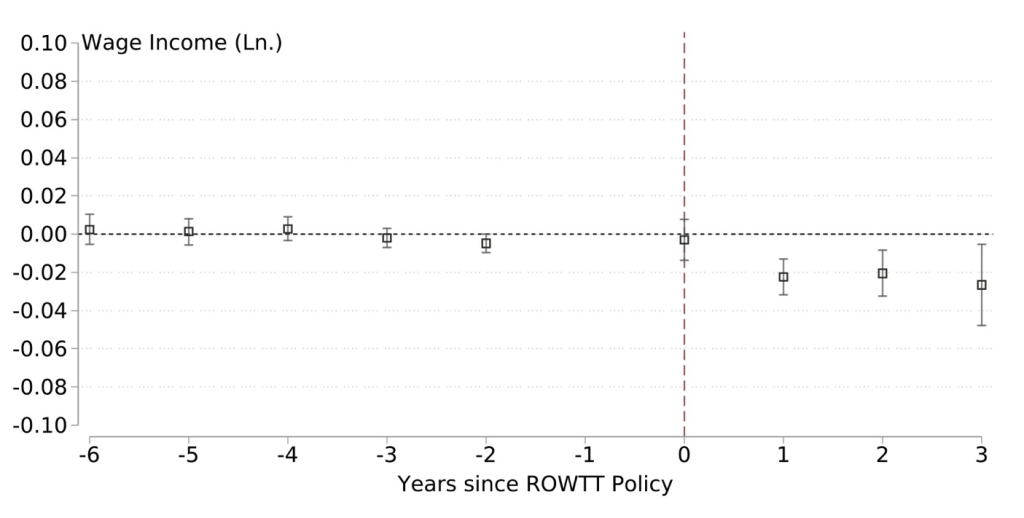

Survey evidence finds that these laws significantly decrease the share of workers reporting that their employer prohibits salary sharing (Hegewisch et al., 2011; Sun et al., 2021). Using a multi-period difference-in-differences (“event study”) design, we find that ROWTT laws decrease the average wages of full-time workers by roughly 2% over the three years following enactment (Figure II).

Figure II: Proportion Change in Average Wages Caused by ROWTT

ROWTT laws have a negligible impact on the wages of unionized occupations where workers have less individual bargaining power. They have a bigger impact on wages of college-educated workers with higher individual bargaining power, whose wages decline on average by 4%. For each of these groups, we cannot reject the hypothesis that employment and workforce composition remained largely unchanged.

We do agree with the adage that “knowledge is power”—but power for whom is the question.

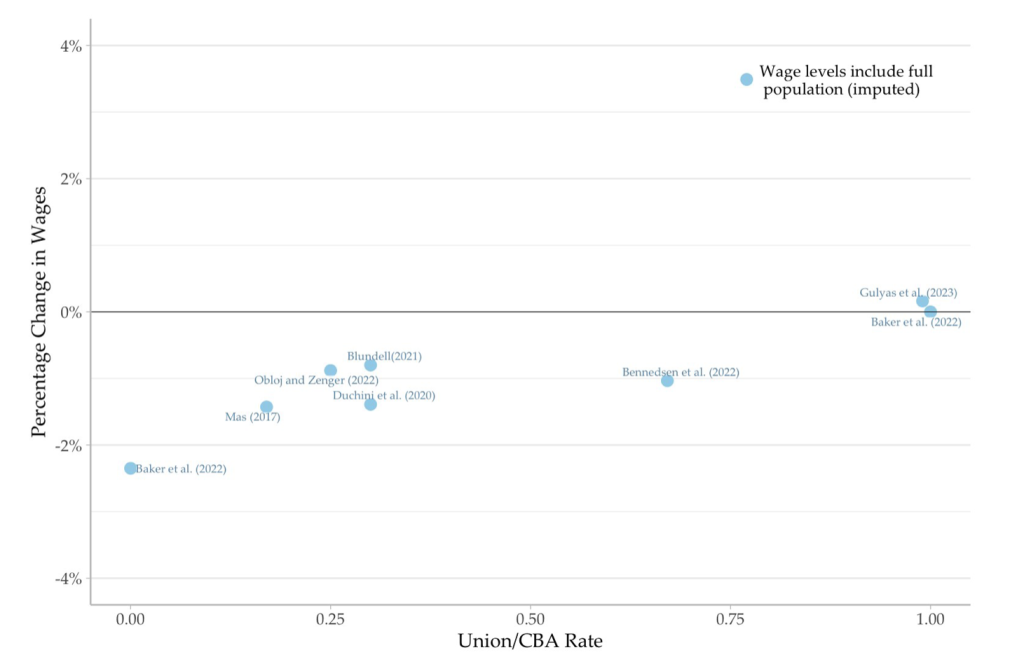

We also conduct a meta-analysis of recent academic studies of pay transparency policies across the world. We find that the unionization rate of the workforce and the relative impact of pay transparency policies on wages follows this pattern: the higher the rate of individual bargaining, the larger the wage declines following pay transparency (Figure III).

Figure III: Meta Analysis: Percent Change in Average Wages by Share

One interpretation of our results that we wish to guard against is that information about pay is necessarily bad for workers. The form of pay transparency we study is internal to the firm: wages are observable only to already-employed workers. By contrast, cross-firm pay transparency, which reveals information about wages outside of the firm, may have very different equilibrium effects.

If cross-firmwage sources are available to all workers, information spillovers between coworkers will have a muted impact on worker knowledge and pay policies of the firm. As a result, renegotiations induced by cross-firm transparency could increase wages (Jäger et al., 2024). Moreover, cross-firmtransparency could lead workers to redirect their applications to higher paying firms (Škoda, 2022), or lead firms to intensify their wage competition (Cullen et al., 2023).

Publicizing salaries across firms may have different equilibrium effects, potentially providing the knowledge that empowers workers rather than employers.

We do agree with the adage that “knowledge is power”—but power for whom is the question. Revealing pay disparities within a firm has merits, equalizing pay and closing the gender wage gap. But it transfers bargaining power to the employer through a credible commitment to set wages lower. Lower wages stem from internal spillovers between negotiations. Transparency policies that avoid these spillovers, such as publicizing salaries across firms, may very well provide the knowledge that empowers workers rather than employers.

This article summarizes ‘Equilibrium Effects of Pay Transparency’ by Zoe Cullen and Bobak Pakzad-Hurson, published in Econometrica in May 2023.

Zoe Cullen is at the Harvard Business School and NBER. Bobak Pakzad-Hurson is at the Department of Economics, Brown University.

References

Michael Baker, Yosh Halberstam, Kory Kroft, Alexandre Mas, and Derek Messacar. Pay Transparency and the Gender Gap. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 15 (2):157–183, 2023.

Morten Bennedsen, Elena Simintzi, Margarita Tsoutsoura, and Daniel Wolfenzon. Do Firms Respond to Gender Pay Gap Transparency? The Journal of Finance, 77(4):2051–2091, 2022.

Jack Blundell. Wage responses to gender pay gap reporting requirements. Centre for Economic Performance Discussion Paper 1750, 2021.

Jack Blundell, Emma Duchini, Stefania Simion, and Arthur Turrell. Pay Transparency and Gender Equality. Mimeo, November 2023.

René Böheim and Sarah Gust. The Austrian Pay Transparency Law and the Gender Wage Gap. IZA Discussion Paper 14206, 2021.

Zoë Cullen, Shengwu Li, and Ricardo Perez-Truglia. What’s My Employee Worth? The Effects of Salary Benchmarking. Mimeo, 2023.

Emma Duchini, Stefania Simion, and Arthur Turrell. Pay Transparency and Cracks in the Glass Ceiling. Mimeo, May 2020.

Andreas Gulyas, Sebastian Seitz, and Sourav Sinha. Does Pay Transparency Affect the Gender Wage Gap? Evidence from Austria. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 15(2):236–255, 2023.

Ariane Hegewisch, Claudia Williams, and Robert Drago. Pay Secrecy and Wage Discrimination. Institute for Women’s Policy Research, 2011.

Simon Jäger, Chris Roth, Nina Roussille, and Benjamin Schoefer. Worker Beliefs About Outside Options. Quarterly Journal of Economics (Forthcoming), 2024.

Alexandre Mas. Does Transparency Lead to Pay Compression? Journal of Political Economy, 125(5):1683–1721, August 2017.

Tomasz Obloj and Todd Zenger. The influence of pay transparency on (gender) inequity, inequality and the performance basis of pay. Nature Himan Behaviour, 6:646–655, 2022.

Samuel Škoda. Directing Job Search in Practice: Mandating Pay Information in Job Ads.ˇ Mimeo, 2022.

Shengwei Sun, Jake Rosenfeld, and Patrick Denice. On the Books, Off the Record: Examining the Effectiveness of Pay Secrecy Laws in the U.S. Institute for Women’s Policy Research, 2021.

Steven R. Williams. Efficient Performance in Two Agent Bargaining. Journal of Economic Theory, 41:154–172, 1987.

1 Since the completion of our article, a new paper, Blundell et al. (2023), which subsumes the analyses of Blundell (2021) and Duchini et al. (2020), has been made public. Including this new study in the following picture would add an observation at (.3,-.002) in Figure III.