Summary

An undergraduate education often brings major benefits but is also a risky investment. Some of those who enroll do not complete the course, and even among those who complete, earnings after graduation will vary widely. This means that a simple debt contract may not be the best way to finance undergraduate study. In research on the US that we summarize here, two economists investigate the current lack of funding contracts in which repayments depend on outcomes after graduation.

A central problem is that students have private information about their prospects, and those with good prospects place less value on contracts that make repayment contingent on outcomes. As high-potential students opt out of the market, offering such contracts becomes less profitable, and adjusting a contract’s terms to cover losses would further reduce its attractiveness to those with good prospects. This mechanism can lead the market to unravel altogether, so that these risk-mitigating contracts are not offered. The authors of the new study show that this can explain the lack of such contracts in the US. They further show that one remedy, government subsidies for such contracts, could improve student welfare by insuring against the risks of college investment.

The riskiness of human capital investments has long been understood. Seventy years ago, Milton Friedman suggested the use of equity-like contracts to finance such investments, but they remain rare in the US, where the provision of student finance for college continues to be dominated by federally-backed debt. The new study explores why there is currently no active market for equity-like contracts. The central idea is that such markets are undermined when applicants have some private information about their prospects. This leads to “adverse selection,” in which the terms of contracts influence the mix of applicants in ways that make offering the contracts less profitable, or even loss-making.

To examine this in more detail, the authors of the new study first show that US college-goers do have some private information about their prospects. In the next step, they derive conditions under which markets for earnings equity and related financial products cannot profitably exist. Combining this framework with the data, they show that adverse selection is sufficient to explain the absence of such products from the US market. The problem is not unique to equity finance. The authors find that markets for other forms of contingent loans – for example, where repayment depends on completion of the course, or on employment afterwards – also unravel due to adverse selection.

One remedy would be for the government to subsidize equity-based alternatives to student loans, so that they are more likely to be offered in the market. The associated government spending could ultimately pay for itself, through higher tax revenues from those who invest in their human capital. At least in the US, this form of subsidy, by helping to reduce the financial risks faced by college students, would lead to much better outcomes.

Main article

Investing in college delivers persistently high returns to both individuals and society but also comes with significant risk. Nearly half of all college enrollees in the US fail to complete their degrees. Conditional on completion, only 85% find work after graduation. Even by age 40, 15% of college graduates have household incomes below $40,000 a year. The most common method of financing college is student debt, which does little to mitigate these risks. 28% of student borrowers default on their debt within five years of repayment. (For the sources of these figures, see the appendix below.)

Economists have long advocated for alternative financial contracts to mitigate the risks of investing in education (Barr et al. 2017; Chapman 2006; Palacios 2004; Zingales 2012). Most famously, Friedman (1955) writes:

“[Human capital] investment necessarily involves much risk. The device adopted to meet the corresponding problem for other risky investments is equity investment… The counterpart for education would be to ‘buy’ a share in an individual’s earnings prospects; … to advance him the funds needed to finance his training on condition that he agree to pay the lender a specified fraction of his future earnings.”

A handful of private companies and post-secondary institutions have attempted to put this theory into practice with “state-contingent” or equity-like contracts for college. The essential idea is that a college student funded by such a contract would later make repayments that depend on outcomes – on how things turn out for the student. Yet despite persistent attempts by private firms, decades of academic advocacy, and increasing college-wage premiums, there is no active private market for equity or state-contingent college financing. Instead, federally-backed debt remains the dominant form of financing higher education in the US. What explains the lack of risk-abating alternatives to student loans?

The main finding is that adverse selection… has unraveled private markets for these products, making them unprofitable for firms to offer.

In the research summarized here, we investigate this question, and show why financial products like equity seldom exist for college-goers. The main finding is that adverse selection – the sorting of individuals with worse-than-average outcomes into insurance-like contracts – has unraveled private markets for these products, making them unprofitable for firms to offer. If this were remedied by government subsidies for risk-abating alternatives to student debt, that would bring major social benefits.

We begin by establishing that college-goers have significant amounts of information about their future life outcomes, such as their future earnings, beyond what could be known to potential financial companies offering alternatives to student debt. We use data from the Beginning Postsecondary Students study (BPS), a 2012 survey that asked over 20,000 first-year college students in the US about a range of expectations for the future, including their likelihood of graduating, expected occupation, and expected salary. These survey responses can be linked to information on students’ outcomes after college, such as their graduation status and earnings in young adulthood.

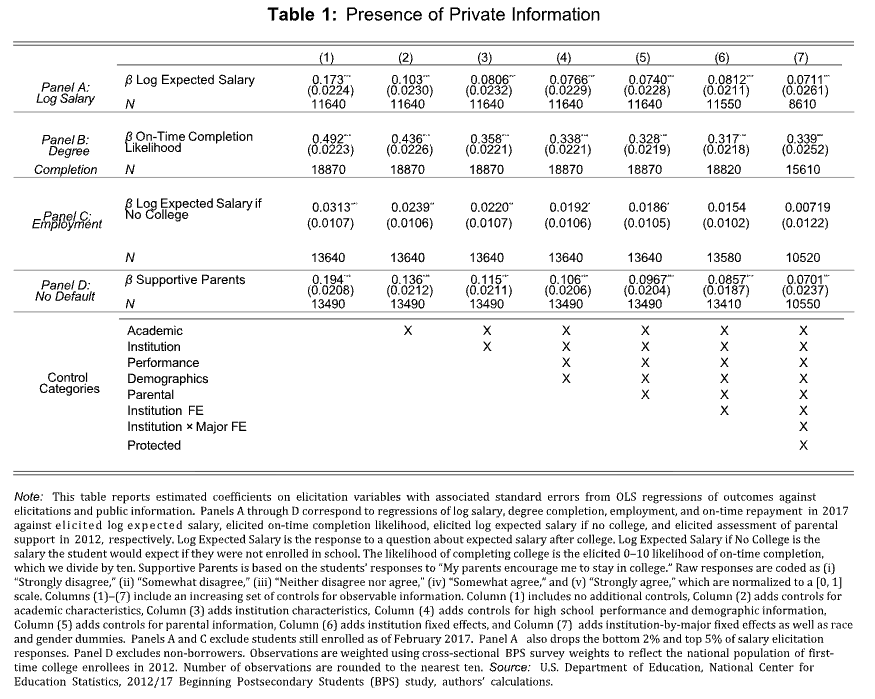

In Table 1, we show that students do indeed hold private information about these future outcomes. For example, Panel A of the table reports statistical estimates that relate salary (in logarithms) to expected salary (also in logarithms) and sets of controls for information the financiers could potentially observe. The expected salary is based on the respondents’ answers to the question “What do you expect your salary to be once you finish your education?”

The first column shows that students’ answers are highly predictive of their actual realized salaries six years later, with a regression coefficient of 0.173. The positive coefficients in the other columns of Panel A indicate that correlation between these subjective elicitations about future salary and realized outcomes persists, even after taking into account a rich set of observable characteristics like age, high-school GPA, and major field of study. So even if financiers screened on these characteristics, students would still have an informational advantage in predicting their future outcomes.

…any price that would profitably finance a given pool of students leads higher-earning students to exit the market, further lowering the average value of the contract

Similarly, Panel B shows that student beliefs about whether they would finish college on time predicted whether they earned their degree by 2017. Panel C shows that additional student beliefs – about salary had they not gone to college – predict employment after college. Finally, Panel D shows that students who report that they have supportive parents are more likely to make loan payments on time.

Why might this privately held information make it difficult for financiers to offer state-contingent or equity-like contracts for college? Suppose that a firm were to offer an equity contract that provides tuition assistance in exchange for a fraction of future earnings. If students know more than the financier about what they might earn, then those expecting relatively low earnings might be more likely to opt into the equity contract than their high-earning counterparts. This strategic sorting lowers the value of equity contracts held by the financier, damaging their bottom line. The financier could lower tuition support to cover their losses, but that would likely lead to further exit of those with relatively high expected earnings. With enough private information, this unraveling process can continue until no contracts are bought or sold.

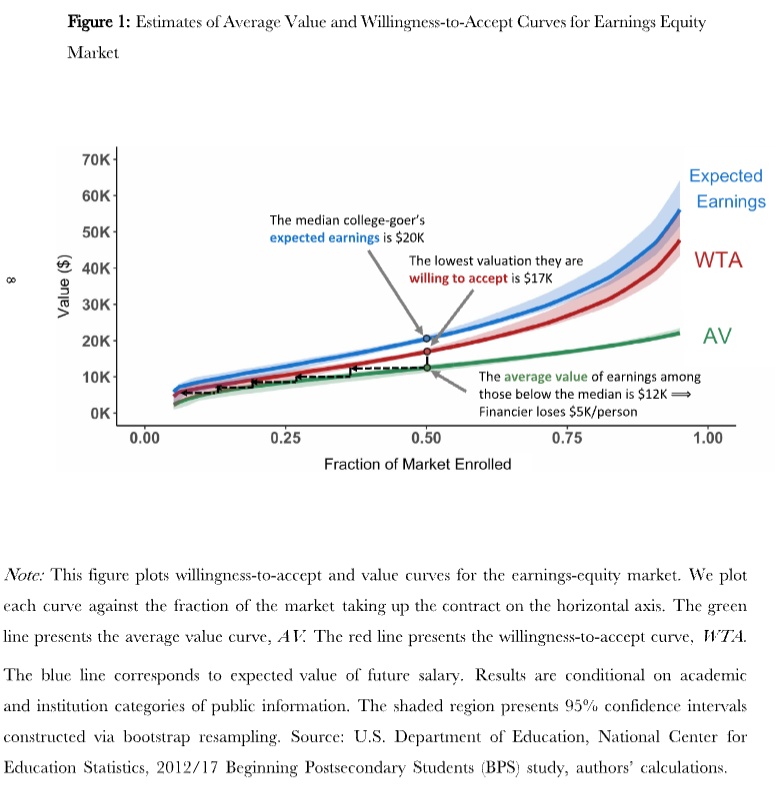

We formalize this idea in a theoretical framework, which reveals the conditions under which markets for earnings equity and related financial products cannot profitably exist. Market existence is seen to depend on two curves: a “willingness-to-accept” (WTA) curve, which corresponds to the minimum amount an individual is willing to accept today to sell a claim on their future outcome, and an “average value” (AV) curve, which corresponds to the average outcome among those willing to accept less for the contract than a given individual. If the AV curve lies below the WTA curve for all individuals, the market unravels; any price that would profitably finance a given pool of students leads higher-earning students to exit the market, further lowering the average value of the contract and pushing the market towards collapse.

We study this market-unraveling condition for several hypothetical contracts: first, an “earnings equity” contract, in which financiers buy “a share in the individual’s earnings prospects”, as Friedman (1955) envisaged. We also study three alternative state-contingent debt contracts. The latter require repayment only if the borrower (1) completes their degree; (2) finds a job; or (3) avoids default on their existing student loans. Our empirical strategy uses the self-reported salary expectations, graduation likelihood, and other elicitations in our data as “noisy” and potentially biased measures of respondents’ beliefs about their future outcomes. We then use the joint patterns (more precisely, the statistical joint distributions) of beliefs and realized outcomes to estimate the WTA and AV curves for each contract of interest. Importantly, we estimate these curves after taking into account academic and institutional information that financiers could use to price financial contracts.

Figure 1 plots our baseline estimates of WTA and AV curves for the earnings-equity market. We plot each curve against the fraction of the market taking up the contract on the horizontal axis. The green line presents the average value curve, AV. The red line presents the willingness-to-accept curve, WTA. The blue line corresponds to expected future salary. These estimated curves suggest that college-goers would have to accept valuations that are significantly lower than actuarially fair for a market to exist.

If private firms cannot profitably finance college with equity or state-contingent debt, should the government subsidize these contracts…?

To see this, note that the median individual expects to earn $20,397. But any equity contract that attracts the median college-goer would also attract everyone with a lower willingness to accept. This group expects to earn just $12,471 on average. To cover the cost of financing these lower-earning individuals, the median individual would therefore have to accept a 39% discount on the value of their future earnings (39 = 100 * ($20,397-$12471)/$20,397). The willingness-to-accept curve suggests they would reject any such contract. We estimate that the median individual is willing to accept a valuation no lower than $17,024, an implied 17% discount below future earnings. In other words, they would pay $1.20 in present value for each dollar of equity financing, which falls short of the $1.64 required for the financier to profit from the contract. Beyond the median, we find that the WTA curve lies above the AV curve more generally; no borrower is willing to cover the financier’s cost of adverse selection, so the market unravels.

These findings are not unique to equity finance. We estimate that markets for completion-contingent loans, employment-contingent loans, and dischargeable debt contracts also unravel due to adverse selection. For the completion-contingent loan market, the median individual has a 63% chance of completing college. Among those who believe their chances of completion are worse than 63%, the average completion rate is just 38%. A profitable contract would therefore provide the median individual with just $0.38 in present-discounted financing for each dollar owed should they graduate, but we estimate this individual is willing to accept no less than $0.56 for each completion-contingent dollar they pledge.

For the employment-contingent loan market, the median individual has a 72% chance of being employed, but the average probability of employment among those with worse employment prospects is just 60%. We estimate that the median individual is willing to accept $0.69 in present-discounted financing for each dollar owed if employed after college, which is more than the $0.60 they would need to accept for the financier to make a profit.

Finally, we consider a dischargeable debt contract that requires repayment only in the event of non-default on the borrower’s existing federal student loans. The median individual has a 85% chance of avoiding default, but the average repayment rate of those who expect higher default likelihood is 61%. The median individual is willing to accept no less than $0.83 in financing for each dollar owed in non-default, which is higher than $0.61. In sum, in all three of these state-contingent loan markets, the WTA curve lies everywhere above the AV curve, and the market unravels.

If private firms cannot profitably finance college with equity or state-contingent debt, should the government subsidize these contracts, as alternatives to federal student loans? We measure the welfare impact of such subsidies by constructing their marginal values of public funds (MVPFs). The MVPF measures the value of the subsidy to beneficiaries, per dollar of the subsidy’s net cost to the government.

Even if we apply aggressive estimates of earnings responses to taxation, our baseline estimates suggest that every $1 spent to open an equity market for college financing delivers a marginal value of public funds (MVPF) of $1.17. But this conservative estimate assumes that opting into risk-mitigating financing would have no effect on an individual’s human capital accumulation. A large literature documents positive effects of grants and loans on future earnings. For example, Gervais and Ziebarth (2019) find that $1,000 in student-loan financing increases earnings by 1.6-2.8 percent ten years after graduation. If we assume that equity financing would yield similar effects on post-graduation earnings, our estimated MVPF would be infinite, meaning that each government dollar spent on equity subsidies would pay for itself through increased tax revenue. Thus, at least in the US, government subsidies for equity-based alternatives to student loans, by addressing the financial risks faced by college students, would lead to much better outcomes.

This article summarizes “Opportunity Unraveled: Private Information and the Missing Markets for Financing Human Capital” by Daniel Herbst and Nathaniel Hendren, published in the American Economic Review in 2024, 114 (7), 2024-72.

Daniel Herbst is an Assistant Professor of Economics at the University of Arizona. Nathaniel Hendren is a Professor of Economics at MIT.

Appendix

The numbers in the introduction are based on the following data and calculations. Employment and completion statistics are calculated six years from enrollment using the 2012 Beginning Post-secondary Students (BPS) study, a representative sample of first-time college enrollees in 2012. Household incomes among forty-year-old college graduates are calculated using the 2012 American Community Survey (Ruggles et al. 2022). Five-year default rates are taken from the 2009 repayment cohort in Table 8 of Looney and Yannelis (2015).

References

Barr, N., Chapman, B., Dearden, L. and Dynarski, S. (2017). “Getting Student Financing Right in the US: Lessons from Australia and England”, Centre for Global Higher Education Working Paper.

Chapman, B. (2006). “Income Contingent Loans for Higher Education: International Reforms”, in E. Hanushek and F. Welch (eds.) Handbook of the Economics of Education, 2, 1435-1503.

Friedman, M. (1955). The Role of Government in Education. Rutgers University Press, New Brunswick, NJ.

Gervais, M. and Ziebarth, N. L. (2019). “Life After Debt: Postgraduation Consequences of Federal Student Loans”, Economic Inquiry, 57(3), 1342-1366.

Looney, A. and Yannelis, C. (2015). “A Crisis in Student Loans?: How Changes in the Characteristics of Borrowers and in the Institutions They Attended Contributed to Rising Loan Defaults”, Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 2015(2), 1-89.

Palacios, M. (2004). Investing in Human Capital: A Capital Markets Approach to Student Funding. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK.

Ruggles, S., Flood, S., Goeken, R., Schouweiler, M. and Sobek, M. (2022). “IPUMS USA: Version 12.0 [dataset]”, IPUMS, Minneapolis, MN.

Zingales, L. (2012). “The College Graduate as Collateral”, The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2012/06/14/opinion/the-college-graduate-as-collateral.html