Summary

US disability programs (USDP) provide access to health insurance and cash benefits, primarily as assistance for people who cannot work because of severe health conditions. However, some have attributed the expansion of US disability programs (USDP) at least in part to nonhealth factors like stagnating wages, resulting in concern that providing benefits to individuals without severe health conditions dilutes the programs’ value.

A simply theoretical model can help assess the validity of this concern. Individuals face two kinds of risk: health risks and nonhealth risks, which include job loss or productivity shocks. To the extent that a particular risk is not completely insured by other means, disability insurance potentially insures or exacerbates that risk, depending on selection into disability insurance receipt on the basis of that risk.

Although mismatches with respect to health (i.e., giving disability benefits to recipients with less severe health conditions and lack of benefits to non-recipients with more severe health conditions) necessarily reduce the extent to which disability insurance insures health risk, the presence of nonhealth risk means that such mismatches might not reduce—and might even increase—the overall value of disability insurance. If individuals with more serious nonhealth shocks are more (less) likely to receive disability benefits conditional on health, then mismatches with respect to health insure (exacerbate) nonhealth risk.

The extent to which mismatches insure nonhealth risk is therefore a critical determinant of the value of potential reforms—and also, ultimately, an empirical question. We quantify the net value of USDP, accounting for nonhealth factors, by using a combination of survey and administrative data to compare disability recipients and non-recipients along a wide variety of health and nonhealth dimensions.

As expected, we find that having a more severe health condition is strongly associated with lower living standards, lower earnings, and more adverse nonhealth events. More novel, we also find that disability recipients with less severe disabilities are, on average, much worse off economically than non-recipients with less severe disabilities and, by many nonhealth measures, are comparable to or even worse off than recipients with more severe disabilities. The strong associations between receiving disability insurance payments and nonhealth shocks conditional on health likely increases the value of USDP by both increasing insurance of nonhealth risk and decreasing distortion costs from discouraging work.

When quantifying this effect, we estimate that the value of USDP, including from insuring nonhealth risks, exceeds that of cost-equivalent tax cuts by 64 percent, creating a surplus worth of $8,700 of government revenue per recipient per year. Moreover, we find that the high value of USDP is, in part, because of—not despite—their mismatches with respect to health. We estimate that benefits to recipients with less severe conditions create a value over cost-equivalent tax cuts of $7,700 per recipient per year, or about three-fourths that of benefits to recipients with more severe conditions. Overall, giving benefits to recipients with less severe health conditions increases the value of USDP considerably, accounting for about half of the total value.

Together, these findings show that USDP target well on the key determinants of the value of receiving disability benefits. Our results suggest that proposed reforms to decrease benefit levels, allowance rates, or awards to individuals with less severe health conditions would reduce the overall value of USDP

Main article

Nonhealth factors like stagnating wages likely explain some of the recent expansion of US disability programs (USDP), prompting concerns about dilution of the programs’ value. The validity of these concerns depends on whether giving disability benefits to recipients with less severe health conditions insures or exacerbates nonhealth risks, which in turn depends on selection into disability insurance receipt on the basis of that risk. Our empirical findings suggest that USDP target well on the key determinants of the value of receiving disability benefits. As a result, benefits to recipients with less severe health conditions account for about half of the programs’ total value.

In the United States, the Social Security Disability Insurance and Supplemental Security Income programs together provide access to health insurance and $200 billion annually in cash benefits to nearly 13 million Americans. This support is provided primarily as assistance for people who cannot work because of severe health conditions. Some have attributed the expansion of US disability programs (USDP) at least in part to nonhealth factors like stagnating wages, resulting in concern that providing benefits to individuals without severe health conditions dilutes the programs’ value.

This raises an important question: What is the net value of USDP, accounting for nonhealth factors? To address this question, we quantify the extent to which USDP insure different risks by comparing disability recipients and non-recipients along a wide variety of health and nonhealth dimensions, including consumption, adverse events like job loss, and resources available to cope with adverse events.

We estimate that the value of these two programs, including from insuring nonhealth risks, exceeds that of cost-equivalent tax cuts by 64 percent, creating a surplus worth $8,700 of government revenue per recipient per year. Moreover, we find that the high value of USDP is, in part, because of—not despite—their “mismatches with respect to health.” By mismatches, we mean benefits to recipients with less severe health conditions and lack of benefits to non-recipients with more severe health conditions. We estimate that benefits to recipients with less severe conditions create a value over cost-equivalent tax cuts of $7,700 per recipient per year, or about three-fourths of the benefits to recipients with more severe conditions, which stand at $9,900.

These are important findings amid the debate about USDP. Benefits to recipients with less severe health conditions do not decrease the value of the two programs. Instead, they increase it considerably, accounting for about half of the total value.

Theory: Nonhealth risk, mismatches with respect to health, and the value of disability insurance

Consider a simple model in which an individual faces two kinds of risk: health and nonhealth. A “health-based perspective” views the objective of disability insurance as providing benefits to an individual if and only if they have suffered a severe health shock. A “value-maximizing” perspective views the objective as maximizing the ex-ante value of disability insurance by providing benefits if and only if the insurance benefit exceeds the distortion cost, that is, if and only if doing so produces a positive (ex-ante) surplus value.

While health is likely a strong indicator of the value of receiving disability benefits, it is not a perfect indicator because individuals face major nonhealth risks as well, including job loss, productivity shocks, and changes in family structure. To the extent that a particular risk is not completely insured by other means, disability insurance potentially insures or exacerbates that risk, depending on selection into disability insurance receipt on the basis of that risk.

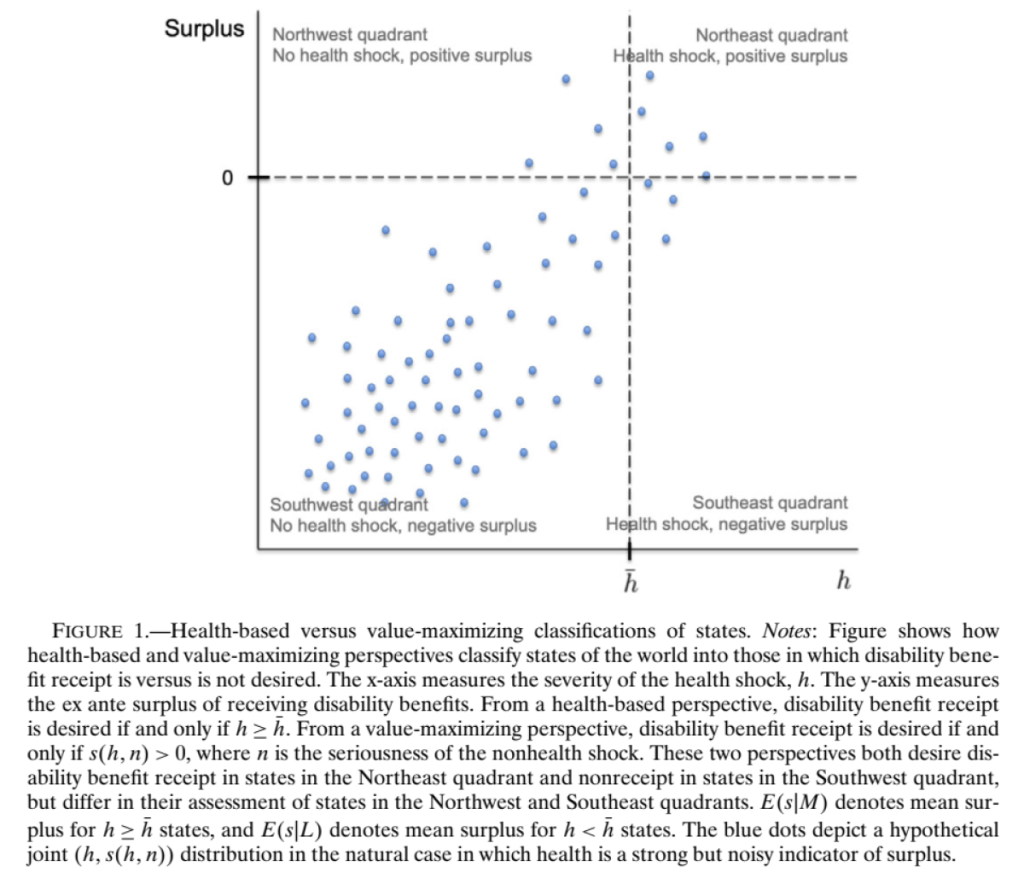

Figure 1 shows how these two perspectives divide the state space into four mutually exclusive, exhaustive sets. It depicts a hypothetical distribution of health h and nonhealth shocks n in the natural case in which health is a strong but noisy indicator of the surplus from receiving disability benefits, . The surplus is defined as the net of the insurance benefit from receiving transfers in high-marginal utility states less the efficiency cost from distorting behavior. The surplus rises with both health shocks and nonhealthy shocks. Health is likely a strong indicator of the value of receiving disability benefits because health shocks increase health spending and limit earning opportunities. These two perspectives agree on providing benefits in the “Northeast” quadrant, states in which the individual suffers a health shock and receiving disability benefits produces positive surplus. They also agree on not providing benefits in the “Southwest” quadrant, states in which the individual does not suffer a health shock and receiving disability benefits produces negative surplus.

Yet the value of receiving disability benefits in a particular state is not entirely determined by the health shock. Insurance value is likely increasing in the seriousness of the nonhealth shock as well, since transfers in states with severe shocks tend to provide valuable insurance, regardless of the underlying source of the shock. In terms of distortions, benefits in states in which “counterfactual earnings” (i.e., earnings if the individual did not receive disability benefits) are low tend to have low efficiency costs regardless of why counterfactual earnings are low. As a result, the two perspectives occasionally disagree on whether benefits should be provided. They disagree about states in the “Southeast” quadrant, in which the individual suffers a health shock but the nonhealth shock is sufficiently favorable (e.g., high spousal earnings) to make surplus negative. The perspectives also disagree about states in the “Northwest” quadrant, in which the individual does not suffer a health shock but the nonhealth shock (e.g., productivity shock not insured by UI) is sufficiently unfavorable to make surplus positive.

In settings with substantial nonhealth risk, the value of disability insurance and the costs of its mismatches with respect to health depend crucially on the extent to which the mismatches insure or exacerbate nonhealth risk, which in turn depends on selection into disability receipt on the basis of nonhealth shocks. Mismatches could either insure or exacerbate nonhealth risk, making their net effect on the insurance value of disability insurance theoretically ambiguous. If individuals with more serious nonhealth shocks are more (less) likely to receive disability benefits conditional on health, then mismatches with respect to health insure (exacerbate) nonhealth risk. Whether selection into disability receipt on the basis of nonhealth shocks is value-enhancing or value-reducing is ultimately an empirical question—and one we aim to answer for U.S. disability programs in the following positive and normative analyses.

Positive analysis: Measuring nonhealth risk and selection into US disability programs

We use a combination of survey and administrative data to establish new facts about the targeting of disability benefits based on nonhealth factors. Our paper details the complete methodology, but, broadly, we compare the characteristics of disability recipients and nonrecipients with different health statuses.

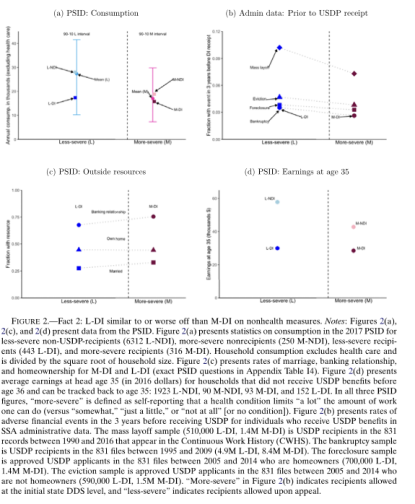

As expected, we find that having a more severe health condition is strongly associated with lower living standards, lower earnings, and more adverse nonhealth events. For example, Figure 2(a) shows that average consumption for households with more severe conditions is just half that of households with less severe conditions. The data are from the Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID).

More novel, we find that—across all the measures we observe—recipients with less severe disabilities are, on average, much worse off economically than non-recipients with less severe disabilities and, by many nonhealth measures, are comparable to or even worse off than recipients with more severe disabilities. For example, Figure 2(a) shows that average consumption among recipients with less severe disabilities is just over half that of non-recipients with less severe disabilities and similar to that of severe disability recipients.

We also find that more severe disability non-recipients are better off on nonhealth measures than both more severe and less severe recipients.

The strong associations between receiving disability insurance payments and nonhealth shocks conditional on health likely increases the value of USDP by both increasing insurance of nonhealth risk and decreasing distortion costs from discouraging work. The next section aims to quantify this effect.

Normative analysis: Estimating the value of US disability programs and their mismatches

Our goal is to estimate the ex-ante net value of disability benefits in different states of the world: the extent to which their ex-ante value exceeds their cost, including cost from the distortions created by disability benefits receipt. Like all welfare analyses, ours relies on assumptions for mapping observable characteristics of individuals into unobservable welfare. These are described in detail in our paper.

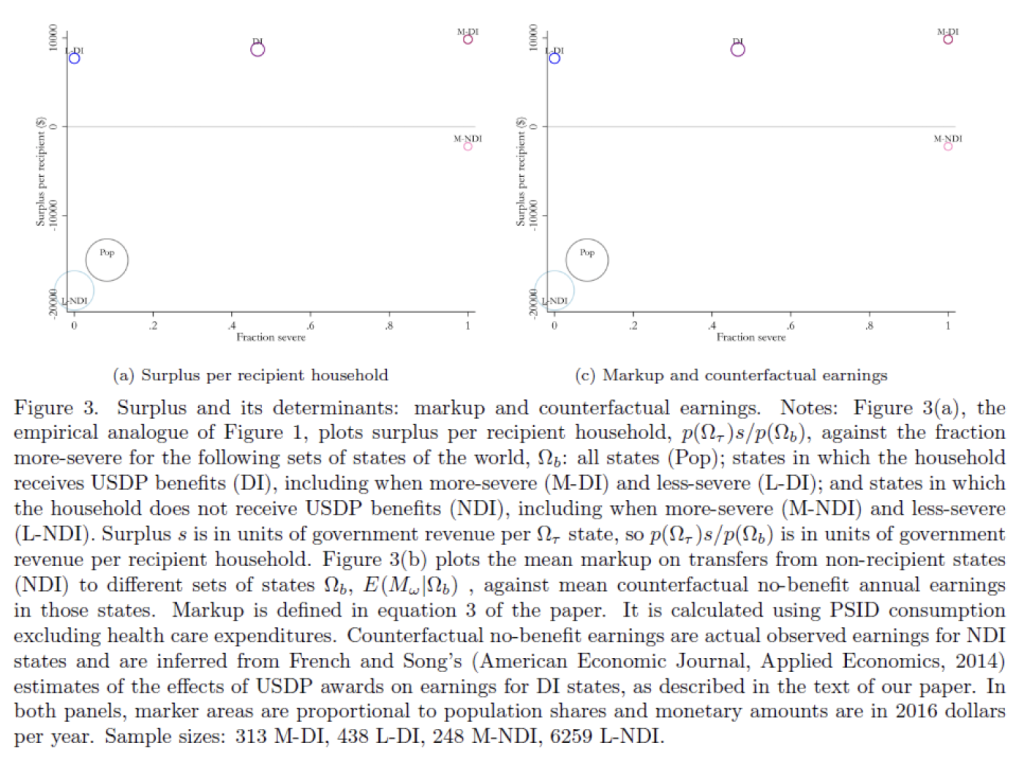

Figure 3(a) shows the empirical analogue of the theoretical Figure 1. The results reveal two key findings. First, U.S. disability programs generate substantial ex-ante surplus. We estimate that disability benefits as a whole are 64% more valuable than tax cuts with the same cost to the government would be. As a result, the annual ex-ante surplus from USDP, measured in terms of government revenue, is $920 per household or $81 billion in aggregate (based on there being about 88 million working-age households in the U.S.). This means that were the government to abolish USDP, the tax cuts necessary to leave individuals unharmed relative to the status quo would cost the government $920 per household per year more than what it would save from abolishing USDP.

Second, USDP mismatches with respect to health are not costly—they are highly valuable. We estimate that mismatches produce an annual ex-ante surplus, in terms of government revenue, of $510 per household or $45 billion in aggregate. This is mostly attributable to benefits in less severe health states; such benefits are worth 57% more than cost-equivalent tax cuts and produce an ex-ante surplus of $440 per household. In fact, benefits in less severe states (L-DI) appear to be nearly as valuable as benefits in more severe states (M-DI).

That USDP mismatches are valuable rather than costly reflects strong selection into disability receipt conditional on health. On average, health is a strong indicator of the value of receiving disability benefits: receiving disability benefits in the average more severe state generates substantial surplus ($5000 on average), whereas receiving disability benefits in the average less severe state reduces surplus significantly (-$16,800 on average). But USDP mismatches are highly selected subsets of their respective severity groups. The states of the world in which an individual would receive disability benefits despite not having a more severe condition have a large surplus from disability benefits ($7700 on average), while the states of the world in which an individual would not receive disability benefits despite having a more severe condition have a negative surplus from disability benefits (-$2200 on average). That USDP mismatches are so favorably selected on the value of receiving disability benefits is in keeping with the findings from the positive analysis that USDP mismatches are favorably selected on a wide variety of nonhealth factors.

To investigate the connections between mismatches with respect to health and insurance against health and nonhealth risk, we performed a decomposition analysis. This revealed that nonhealth risk is a key driver of the overall value of USDP, with about half of the value of USDP coming from insuring risks other than that of having a more severe health condition.

Discussion and conclusions

The public debate over U.S. disability programs centers on concerns about individuals with less severe health conditions receiving benefits. We find that not only are these programs highly valuable, their benefits to individuals with less severe health conditions actually increase their value. Together, our findings show that these programs target well on the key determinants of the value of receiving disability benefits. Our results suggest that proposed reforms to decrease benefit levels, allowance rates, or awards to individuals with less severe health conditions would reduce the overall value of USDP.

Our findings help reconcile two strands of the debate about USDP. The first strand raises concerns about these programs, including that some recipients may not have severe health conditions, that labor market shocks increase disability enrollment, and that disability programs reduce the labor supply of marginal recipients. The second strand quantifies the welfare effects of various reforms to USDP. This strand typically finds that expanding USDP would increase welfare. Our results help reconcile the tension between these two strands by demonstrating that the nonhealth drivers of enrollment drive up not only the cost but also the benefit from insuring nonhealth risk.

The importance of nonhealth risk for the value of U.S. disability programs may be just one example of a broader phenomenon. No program exists in a vacuum—its effects reflect the diversity of risks in the economy, how well-insured those risks are by other programs and institutions, and how its features shape selection into the program. We find that USDP insure risks well beyond health, and that this “incidental” role is central to their overall value. Other programs might be similar in having their costs and benefits driven in large part by factors outside of their core aims. The extent to which they do is an empirical question that future research could investigate using similar methods.

This article summarizes ‘Beyond Health: Nonhealth Risk and the Value of Disability Insurance’ by Manasi Deshpande and Lee M. Lockwood, published in Econometrica in July 2022.

Manasi Deshpande is at the Kenneth C. Griffin Department of Economics at the University of Chicago and the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER). Lee M. Lockwood is at the Department of Economics of the University of Virginia and the NBER.