Summary

Health care markets have become increasingly concentrated through mergers and acquisitions. This consolidation can lower costs due to economies of scale and improve patient outcomes through coordinated care. However, greater concentration may also result in higher prices or lower quality. A recent paper studies the effects of mergers and acquisitions in the dialysis industry, which makes up 6% of total Medicare expenditures (Eliason et al., 2020).

The dialysis industry has consolidated over the past three decades, with the share of independently owned dialysis facilities falling from 86% to 21%. This new research uses detailed claims data to show directly how large chains transfer their corporate strategies to the approximately 1,200 independent facilities they acquired between 1998-2010.

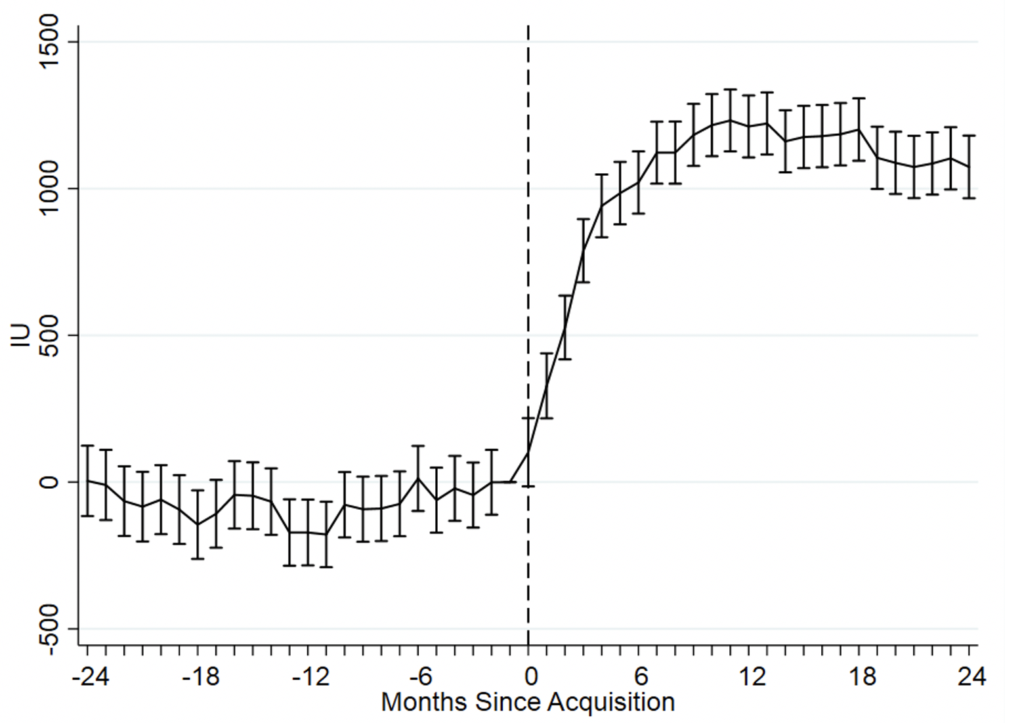

On average, acquired facilities see their reimbursements increase and their costs decreasing, which may reduce the quality of care. Patients receive 128.9% higher doses of EPO after their facilities are acquired by a large chain, and acquired facilities also increase their use of the iron deficiency drug Venofer relative to Ferrlecit, a near-perfect substitute that offered lower reimbursements. On the cost side, large chains reduce expenses by replacing high-skill nurses with lower-skill technicians, by increasing the patient-load of each employee, and by increasing the number of patients treated at each dialysis station. Stretching resources this way potentially reduces the quality of care received by patients, as over-burdened staff are more error prone and less able to maintain proper standards of cleanliness. Patients at acquired facilities are 6.1% more likely to be hospitalized in a given month, and the survival rate for new patients falls by 1.3-3%. The acquisitions have mixed results on other measures of clinical quality.

Acquisitions do not occur randomly and acquired facilities are likely differ in important, potentially unobservable ways from those that are not acquired. This means that these findings—like much of the literature on merger effects—could face multiple threats to identification. The authors are able to mitigate these threats, however, through the use of detailed data on outcomes and condition severity, the long length of their data panel, and the use of patient-level fixed effects that control for time-invariant characteristics.

Standard models of regulated markets predict that a facility in a more competitive market will offer higher quality care to attract more patients, on the assumption that patient demand responds to facility quality. In dialysis, however, that assumption fails to hold—patients show little response to changes in quality and rarely switch facilities. Changes in market power alone cannot therefore explain the decline in quality after a takeover. Instead, the strategy of the acquiring chain largely determines how patients fare following an acquisition.

These findings have two important implications. First, although current antitrust laws prohibit acquisitions that substantially decrease competition, this paper demonstrates that the diffusion of firm strategy is an additional mechanism through which acquisitions may harm consumers. Second, these results illustrate the importance of well-designed payment systems in controlling health care costs and improving patient outcomes. By improving the design of Medicare’s payment systems, policy makers can simultaneously reduce costs and improve outcomes.

Main article

A recent paper studies the effects of mergers and acquisitions in the dialysis industry. When independent facilities are acquired by large chains, their reimbursements increase, their costs decrease, and their quality of patient care deteriorates across most metrics. These changes in care and quality appear to be due to the strategy of the acquiring chain, rather than the characteristics of the acquired facility or changes in market power. These findings imply that acquisitions may harm patients due to the diffusion of firm strategy independently of any decrease in competition, and also illustrate the importance of well-designed payment systems in controlling health care costs and improving patient outcomes.

Health care markets have become increasingly concentrated through mergers and acquisitions. Proponents of this consolidation cite several potential benefits, including lower costs due to economies of scale and better patient outcomes through coordinated care. Greater concentration may also result in higher prices or lower quality, however. In a recent paper, funded in part by a grant from the National Science Foundation, we study the effects of mergers and acquisitions in the dialysis industry (Eliason et al., 2020). With total Medicare reimbursements for treating the nation’s 430,000 dialysis patients amounting to about $33 billion each year, or 6% of total Medicare expenditures, this is an important market to study.

Like many parts of U.S. health care, the dialysis industry has consolidated over the past three decades, with the share of independently owned dialysis facilities falling from 86% to 21%, and with two large publicly traded corporations, DaVita and Fresenius, now owning 65% of facilities. Previous studies of health care consolidation have typically considered only broad measures of competition and outcomes—by showing, for instance, that more-concentrated hospital markets have higher mortality rates. Comparatively less work has examined the precise channels through which mergers and acquisitions ultimately cause health outcomes to change, which motivated us to use detailed claims data from the dialysis industry to show directly how large chains transfer their corporate strategies to the approximately 1,200 independent facilities they acquired between 1998-2010.

On average, acquired facilities increase their reimbursements and decrease their costs, but experience a decline across most measures of patient quality

We find that acquired facilities alter their treatments both by increasing reimbursements and by decreasing costs. One important way facilities capture higher payments from Medicare is by increasing the amount of drugs they administer to patients, for which Medicare paid providers a fixed per-unit rate during our study period. The most notable of these is EPOGEN (EPO), an injectable drug used to treat anemia, which was Medicare’s largest drug expenditure in 2010, totaling $2 billion. Perhaps reflecting the profits at stake, we find that patients receive 128.9% higher doses of EPO after their facilities are acquired by a large chain, as shown in Figure 1. Similarly, acquired facilities increase their use of the iron deficiency drug Venofer relative to Ferrlecit, a near-perfect substitute that offered lower reimbursements. On the cost side, large chains reduce expenses by replacing high-skill nurses with lower-skill technicians, by increasing the patient-load of each employee by 11.9%, and by increasing the number of patients treated at each dialysis station by 4.6%.

Figure 1: EPO Doses at Acquired Dialysis Facilities

Stretching resources this way potentially reduces the quality of care received by patients, as over-burdened staff may be more error prone and less able to maintain proper standards of cleanliness. Reflecting this, patients at acquired facilities are 6.1% more likely to be hospitalized in a given month, while the survival rate for new patients falls by 1.3-3%, depending on the time horizon considered. In addition, new dialysis patients who start treatment at an acquired facility are 9.4% less likely to receive a kidney transplant or be added to the transplant waitlist during their first year on dialysis, a reflection of worse care because transplants provide both a better quality of life and a longer life expectancy than dialysis.

The acquisitions have mixed results on other measures of clinical quality. Although we find that patients are 10.3% less likely to have hemoglobin levels below the desired range for effective anemia management post acquisition, they are also 9.8% more likely to have hemoglobin values that are too high and 5.3% less likely to have hemoglobin values within the recommended range. The only outcome for which we find unequivocal evidence that quality improves after an acquisition is the urea reduction ratio, a measure of the waste cleared during dialysis, with patients at acquired facilities 2.5% more likely to have adequate clearance levels. Despite patients mostly receiving worse care following an acquisition, acquired facilities increase their per-treatment Medicare reimbursements by 7.5%, amounting to $274.5 million in additional spending across our sample and reflecting worse value for Medicare.

Changes in care and quality appear to be due to the strategy of the acquiring chain, rather than the characteristics of the acquired facility or changes in market power

Like much of the literature on merger effects, our findings may face multiple threats to identification, as acquisitions do not occur randomly and acquired facilities likely differ in important, potentially unobservable ways from those that are not acquired. For instance, facilities may systematically alter their patient mix after being taken over, in which case the changes in outcomes we attribute to changes in ownership may actually stem from changes in facilities’ demographics. Similarly, chains may disproportionately target facilities located in areas with more lucrative patients, potentially biasing our estimates of how reimbursements change following an acquisition.

We overcome these challenges through the uniquely detailed nature of our data. Our dialysis claims data contain repeated measures of patients’ clinical outcomes and precise measures of their conditions’ severity, allowing us to mitigate concerns about a changing mix of patients. Furthermore, the long length of our panel allows us to observe patients with the same characteristics being treated at the same facility both before and after an acquisition, permitting us to identify the effects of an acquisition solely from within-facility changes in ownership. Finally, in many cases we can estimate specifications with patient-level fixed effects that control for any of their time-invariant characteristics, a particularly conservative approach for measuring how an acquisition affects patients’ treatments and outcomes.

We conclude our paper by considering whether an acquisition’s effect on market power (i.e., competition in the surrounding area) can explain the changes we observe for patient outcomes, as would be predicted by standard models of regulated markets with endogenous product quality. With prices set administratively for Medicare patients, these models predict that a facility in a more competitive market will offer higher quality care to attract more patients, given the assumption that patient demand responds to facility quality. In dialysis, however, that assumption fails to hold: patients show little response to changes in quality and rarely switch facilities, as discussed in Eliason (2019). We therefore find very similar qualitative and quantitative results across all of our outcomes when comparing acquisitions that increased market concentration with those that did not. As such, changes in market power alone cannot explain the decline in quality after a takeover, which implies that the strategy of the acquiring chain, rather than the subsequent increased concentration of the market, largely determines how patients fare following an acquisition.

These findings have implications for antitrust regulation and health care design

These findings have received immediate attention from policymakers and journalists. They have been cited as an example of non-reportable consolidation under the Hart-Scott-Rodino Act by FTC Commissioner Christine Wilson, for instance, and highlighted by Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Michael Hiltzik in his article on health care competition. [1] Although current antitrust laws prohibit acquisitions when “the effect of such acquisition may be substantially to lessen competition, or to tend to create a monopoly,”[2] our results demonstrate an additional mechanism through which acquisitions may harm consumers—the diffusion of firm strategy. As firm strategy, rather than a change in market concentration, appears to explain the declining quality of care, the harmful acquisitions of dialysis facilities may fall outside the current purview of antitrust regulators.

In addition, our results illustrate the importance of well-designed payment systems in controlling health care costs and improving patient outcomes. As we show in the case of EPO, poorly structured reimbursement schemes can lead providers to behave in ways that not only waste resources but also harm patients. By improving the design of Medicare’s payment systems, policy makers can simultaneously reduce costs and improve outcomes. Progress in this direction is already underway with the ESRD Prospective Payment System and Quality Incentive Programs, as we show in a related paper (Eliason et al., 2020B).

This article summarizes ‘How acquisitions affect firm behavior and performance: Evidence from the dialysis industry’ by Paul Eliason, Benjamin Heebsh, Ryan C. McDevitt, and James W. Roberts, published in The Quarterly Journal of Economics in February 2020.

Paul Eliason is at the Department of Economics, Brigham Young University. Benjamin Heebsh is at the Federal Trade Commission. Ryan C. McDevitt is at the Fuqua School of Business, Duke University. James W. Roberts is at the Department of Economics, Duke University, and NBER.

[1] Cf., respectively, FTC and L.A. Times.

[2] 15 U.S.C. § 18