Summary

The income tax base in developing countries covers only a fraction of the income distribution, which means that these countries rely primarily on indirect consumption taxes to collect revenue. These indirect consumption taxes, which include value-added tax (VAT), are often perceived as regressive or, at best, distributionally neutral.

We test two channels that could make consumption taxes progressive in practice in developing countries: the de jure tax exemption of both necessity goods such as food items and products arising from the informal sector. These two channels could make consumption taxes more equitable if households spend a shrinking slice of their budget on food or in the informal sector as they become richer. We assemble a micro database of household-level expenditure surveys from 32 developing countries, using the store type reported for each purchase to proxy for informal consumption.

The database reveals the existence of a downward sloping Informality Engel Curve (IEC): the informal budget share steeply declines with household income in each country. As a result, VAT is strongly progressive when it applies a uniform tax rate to all formal goods: the effective consumption tax rate of the richest decile of households progressive for a country at the mean income level of our sample is over twice that of the poorest decile. In contrast, the progressivity gain from exempting food products (while taxing non-food) is low, since a large share of poor households’ food consumption occurs in informal stores and from home production.

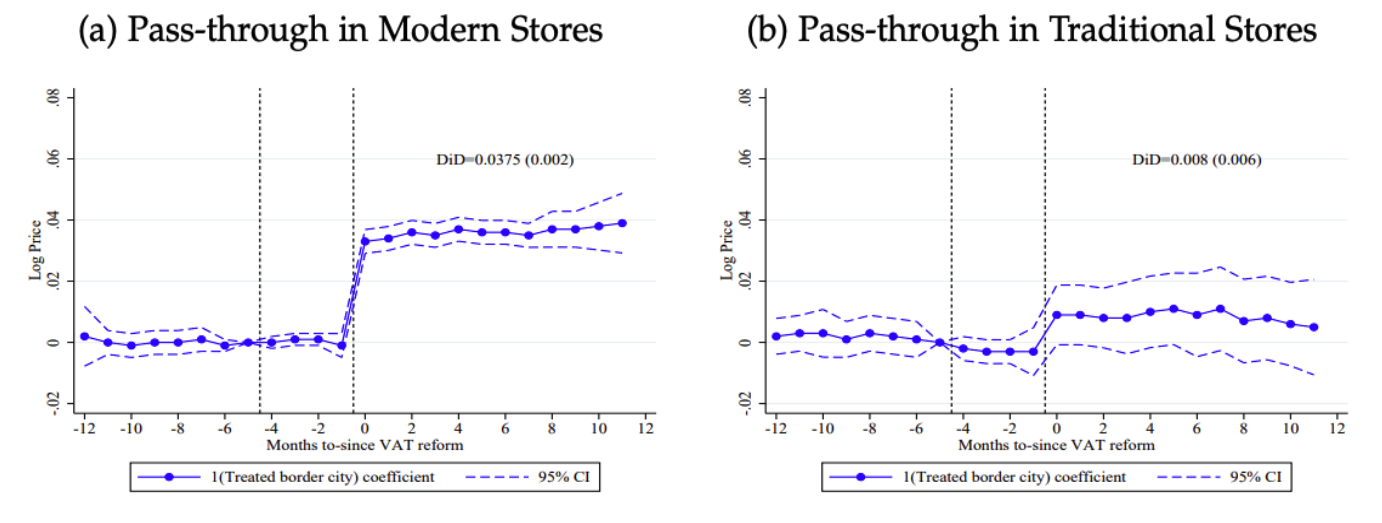

These baseline results assume a zero pass-through of taxes to consumer prices in informal stores, and a full pass-through of taxes to prices in formal stores. In practice, pass-through of taxes to informal prices is likely to be higher than zero. Pass-through rates in the presence of an informal sector had not, however, been estimated before due to an absence of data. This study finds a small, but non-zero, tax pass-through in traditional stores (16%), and a large pass-through in modern stores (75%) after a 2014 change in the consumption tax rate in Mexico. Consumption taxes remain progressive using these more realistic pass-through estimates with our dataset: top decile households face an effective tax rate that is 70% higher than that of bottom decile households under a uniform indirect tax rate.

To measure the impact of consumption taxes on inequality, the study calibrates optimal commodity taxes. Setting an optimal uniform rate reduces the Gini coefficient by 2% on average across countries: 1% in low-income countries and 3% in upper middle-income countries. These are non-trivial reductions in inequality, though lower than what could be achieved via progressive income taxation, or well-targeted transfer programs.

In addition to challenging the conventional wisdom on the distributional effects of consumption taxes, these results have two other important implications for tax policy. First, the widespread policy of reduced rates on necessities such as food has limited redistributive potential once informal consumption is accounted for, which provides an argument against extensively deploying rate differentiation on food items, particularly in poorer countries. Second, these results caution that any benefits from reducing the size of the informal sector—which may become easier due to the growth of digital technologies—must be weighed against their distributional effects.

Main article

Indirect consumption taxes—which are the primary means by which many developing countries collect revenue—are often perceived as distributionally neutral, at best. This study illustrates, however, that the de facto tax exemption of products arising from the informal sector can render consumption taxes progressive, since households spend a shrinking slice of their budget on these items as they get richer. The empirical results suggest that reducing rates on necessities such as food has limited redistributive potential once informal consumption is accounted for, which provides an argument against extensive rate differentiation for food items. Policy makers should also consider distributional effects when considering expanding consumption taxes to increasingly smaller firms.

Rich countries achieve significant redistribution via broad-based income taxes, but the income tax base covers only a fraction of the income distribution in developing countries, due in part to enforceability constraints (Jensen, 2022). Instead, developing countries rely primarily on indirect consumption taxes to collect revenue, such as the value-added tax (VAT), which are perceived as regressive or, at best, distributionally neutral.

Yet two channels could make consumption taxes progressive in practice in developing countries. The first channel is the de jure tax exemption of necessity goods such as food items. The second channel is the de facto tax exemption of products arising from the informal sector. In this study’s context, the informal sector is defined as the set of VAT-unregistered firms, which are typically small scale. These firms are difficult to monitor, and tax agencies often choose to exempt them from VAT when their sales are below a specified threshold.

De jure tax exemptions on food items and distributional patterns of consumption from the informal sector could make consumption taxes progressive.

These two channels could make consumption taxes more equitable since the composition of goods that households typically purchase changes as the household becomes richer. A tax policy that exempts products on which households spend a shrinking slice of their budget as they become richer—while continuing to tax other products the same—should thus be progressive, since it affects the rich proportionally more. If poorer households spend a bigger share of their disposable income on food, for instance, then exempting food would allow governments to redistribute. Similarly, the presence of large informal sectors in developing countries could make consumption taxes more progressive, if the budget share spent in the informal sector decreases with household income.

This study assembles a micro database of household-level expenditure surveys from 32 developing countries that range from low income (where GDP per capita is the lowest, e.g., Burundi) to upper-middle income (e.g., Chile). Since expenditure surveys do not ask if taxes were paid on a purchase (and respondents might not know), the study uses the store type reported for each purchase to proxy for informal consumption by classifying store types as belonging to the traditional sector or the modern sector. Traditional stores include street stalls, corner shops, open markets, and home production (e.g., food consumed directly from a household’s farm production). Modern stores include chain stores, supermarkets, and department stores. This classification is motivated by the vast disparities in consumption by store type across countries. Moreover, modern and traditional stores differ in key characteristics that determine formality, including size, organizational structure, and interaction with third parties. In the baseline formality assignment, the study assumes that taxes are remitted on purchases from modern stores but not from traditional stores, consistent with the evidence of increasing tax compliance with firm size (e.g., Naritomi 2019, Basri et al 2021).

This study assembles a micro database of household-level expenditure surveys from 32 developing countries.

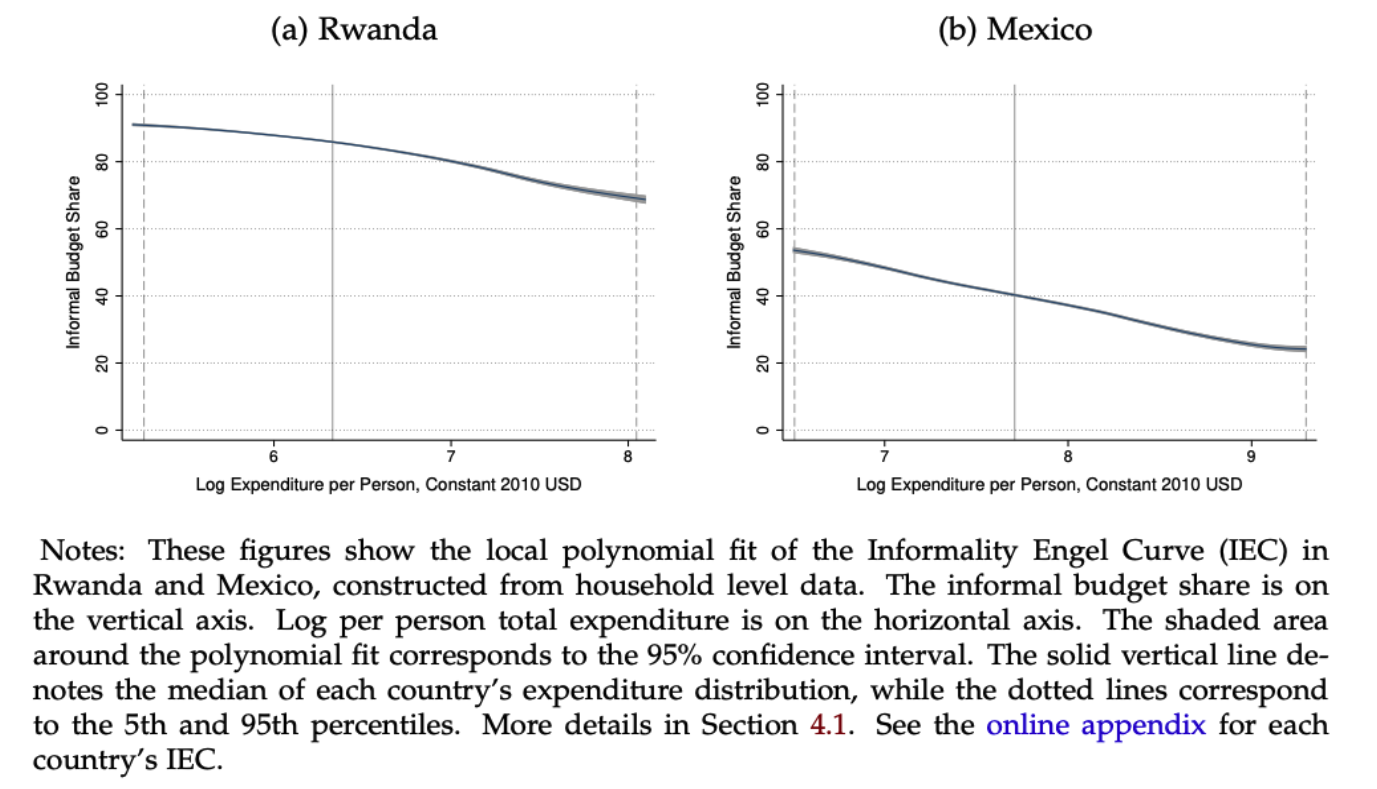

The relationship between Household income and the share of total consumption spent on a particular good is referred to as the Engel curve for that good. The database assembled for this study reveals the existence of a downward sloping Informality Engel Curve (IEC): the informal budget share steeply declines with household income in each of the 32 countries. Figure 1 shows this relation for two countries at different stages of economic development, Rwanda and Mexico.

Figure 1: Selected Informality Engel Curves

On average, doubling a household’s income, within a country, is associated with a 10-percentage point decrease in consumption from informal stores. Accounting for informality also significantly alters the goods-level patterns of consumption. This is especially true for food and non-food goods: while the overall food Engel curve is steeply downward sloping in all countries, the formal food Engel curve is relatively flat in most countries and even has a small but positive slope in the poorest countries—meaning that food consumption from modern formal stores increases as households become richer.

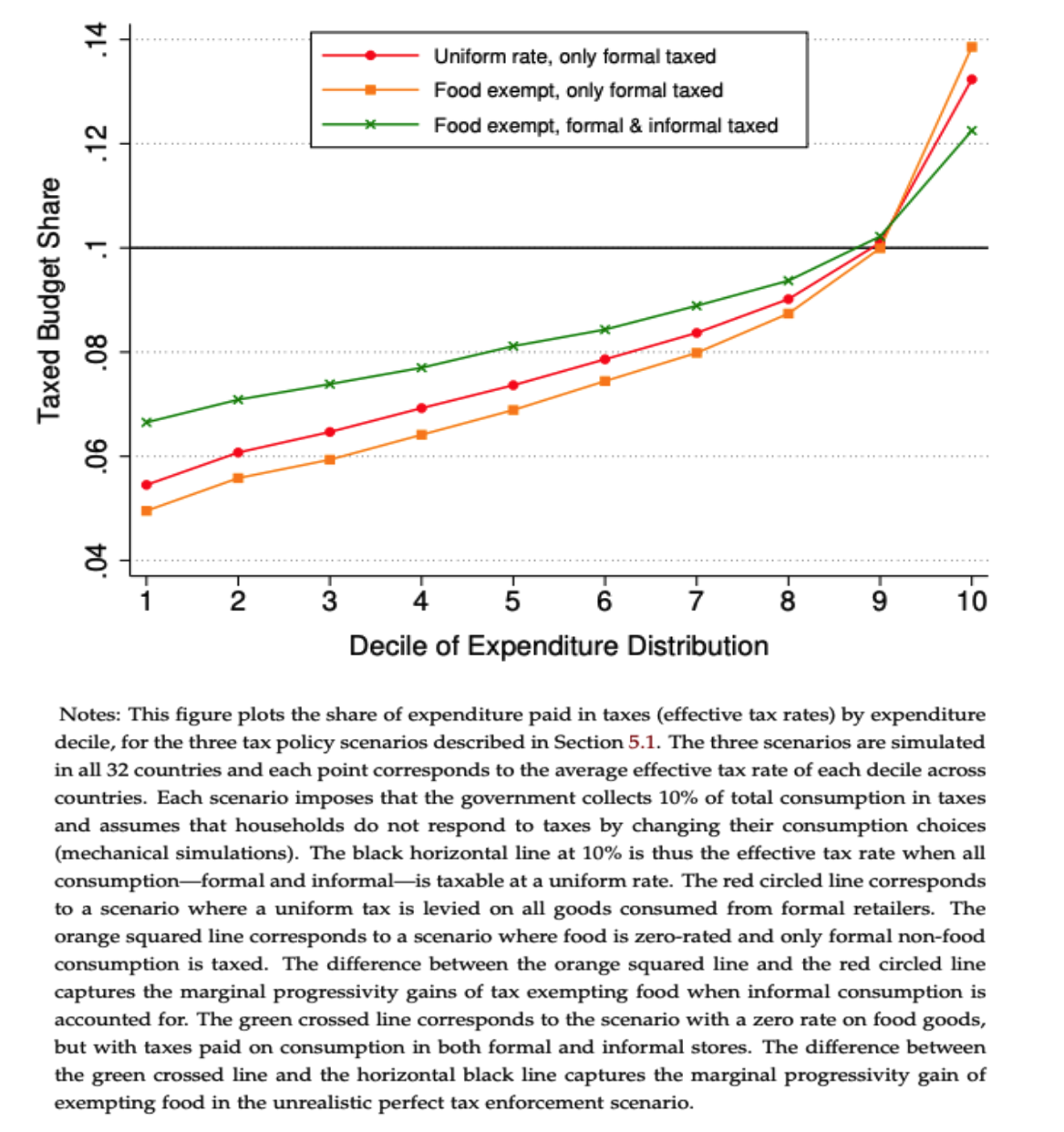

These patterns determine the progressivity of consumption taxes. A tax is progressive if the effective tax rate (ratio of taxes paid to household income) rises with household income. For a country at the mean income level of our sample, VAT is strongly progressive when it applies a uniform tax rate to all formal goods: the effective consumption tax rate of the richest decile of households is over twice that of the poorest decile. This is depicted in Figure 2 below, as the red dotted line.

Informal budget shares decline with household income, rendering VAT strongly progressive when it applies a uniform rate to all formal goods.

In contrast, the progressivity gain from exempting food products (while taxing non-food) is low, since a large share of poor households’ food consumption occurs in informal stores and from home production. This orange squared line in Figure 2 shows the distributional consequence of exempting food items, once we consider that only the formal sector pays taxes: the orange line only shifts very slightly down compared to the red dotted line, implying that the equity gains from exempting food items are very limited once informal consumption is accounted for. Tax exemptions or rate reductions for food items are a ubiquitous policy worldwide, motivated by distributional purposes, yet failing to account for the informal sector leads to a large overestimation of equity gains from food exemptions, and particularly so in poorer countries.

Figure 2: Progressivity of Tax Policy Scenarios (Average Across Countries)

The baseline results above assume a zero pass-through of taxes to consumer prices in informal stores, and a full pass-through of taxes to prices in formal stores. In practice, pass-through of taxes to informal prices is likely to be higher than zero: informal stores might purchase some goods from formal suppliers (and thus this share of value added would bear taxes); competition between formal and informal stores could imply that when a tax hike pushes prices up in formal stores, informal stores also partly raise their prices.

Setting an optimal uniform rate and considering the informal sector reduces inequality by 2% on average across countries (as measured by the GINI coefficient).

Pass-through rates in the presence of an informal sector have not been estimated before, due to the paucity of data on informal prices and lack of variation in indirect tax rates. A reform in Mexico changed the consumption tax rate from 11% to 16% in 2014 for firms located in municipalities close to foreign borders. By combining price quotes from both modern and traditional stores (to proxy for formal and informal prices) and a difference-in-differences design, the study finds a small, but non-zero, tax pass-through in traditional stores (16%), and a large pass-through in modern stores (75%), as shown in Figure 6 below. Applying the more realistic differential pass-through estimates from Mexico to all countries still implies progressivity of consumption taxes, with top decile households facing an effective tax rate that is 70% higher than that of bottom decile households under a uniform indirect tax rate.

To measure the impact of consumption taxes on inequality, the study calibrates optimal commodity taxes, which differ between food and non-food items, and which take into account the presence of an informal sector (an adapted Diamond (1975) multi-person model). Setting an optimal uniform rate reduces the Gini coefficient by 2% on average across countries: 1% in low-income countries and 3% in upper-middle-income countries. With optimal rate differentiation between food and non-food items, the inequality reduction ranges from 1.1% to 3.9%. These are non-trivial reductions in inequality, yet they are lower than what could be achieved via progressive income taxation, or well-targeted transfer programs.

Developing countries rely primarily on indirect consumption taxes—which are perceived as distributionally neutral, at best—to collect revenue

What are the implications of these results for tax policy? First, the study challenges the common wisdom on the distributional effects of consumption taxes, which are found to be mildly progressive in developing countries. Optimal consumption taxes can lower inequality by 2-3% (Gini coefficient), which is roughly as much as the inequality reduction of personal income taxes that are actually implemented in developing countries. At the same time, improving direct tax and transfer systems should remain a priority for developing countries to further their distributional goals.

Second, the widespread policy of reduced rates on necessities such as food has limited redistributive potential once informal consumption is accounted for. Since rate differentiation could lead to more tax evasion and higher administrative costs (Ebrill and Keen, 2001), this finding cautions against extensively deploying rate differentiation on food items, particularly in poorer countries. Finding appropriate compensation mechanisms for poorer households could allow developing countries to phase out such tax exemptions.

Benefits from reducing the size of the informal sector must be weighed against their distributional effects.

Third, tax administrations often focus enforcement on large firms (Basri et al., 2019) and exempt firms below a size threshold (Keen and Mintz, 2004). Going forward, the growth of digital technologies may lower enforcement costs and make it possible to bring smaller firms into the tax net. The results in this study do not imply that efforts to tax small firms should be abandoned, but caution that any benefits from reducing the size of the informal sector must be weighed against their distributional effects. Policy decisions—such as the location of the VAT exemption threshold—should consider equity costs, in addition to compliance burdens and revenue considerations.

This article summarizes ‘Informality, Consumption Taxes, and Redistribution’ by Pierre Bachas, Lucie Gadenne, and Anders Jensen, published in The Review of Economic Studies in September 2023.

Pierre Bachas is at the ESSEC Business School and the World Bank. Lucie Gadenne is at the Queen Mary University of London, the Institute for Fiscal Studies, and the Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR). Anders Jensen is at the Harvard Kennedy School and the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER).

References

Basri, M. C., M. Felix, R. Hanna, and B. A. Olken (2021): “Tax Administration versus Tax Rates: Evidence from Corporate Taxation in Indonesia”, American Economic Review,111, 3827-71

Ebrill, L. P. and M. Keen (2001): Modern VAT, International Monetary Fund.

Diamond, P. A. (1975): “A Many-Person Ramsey Tax Rule,” Journal of Public Economics, 4, 335–342.

Keen, M. and J. Mintz (2004): “The Optimal Threshold for a Value-Added Tax,” Journal of Public Economics, 88, 559 – 576.

Jensen, A. (2022): “Employment Structure and the Rise of the Modern Tax system,” American Economic Review, 112, 213–34.

Naritomi, J. (2019): “Consumers as Tax Auditors,” American Economic Review, 109.