Women are often paid less than men, they are often underrepresented in leading positions, and their careers develop at a slower pace than those of men. Here, we ask to what extent these differences can be explained by childbearing. To evaluate the career cost associated with having children, we consider women’s decisions regarding labor supply, occupation, fertility and savings. We evaluate the life-cycle career cost of children to be equivalent to 35 percent of a woman’s total earnings. We further show that part of this cost arises well before children are born through selection into careers characterized by lower wages but also lower skill depreciation.

equality

Marital choices and widening economic inequality

While much attention has been paid to the education premium on the labor market, little study has been devoted to the marriage market. Looking back at four decades of US marriages, this research finds that more highly educated people are more likely to marry and that their spouses tend to be of similar academic achievement. Additionally, more educated couples invest greater time in developing their children’s potential. Meanwhile, children from less educated households enjoy fewer resources and are less likely to marry highly educated spouses, the upshot of which could be less social mobility and wider economic inequality.

Gender quotas and the crisis of the mediocre man

More than 100 countries have a gender quota, or an effort to increase gender equality and representation, in their political system. Many opponents of gender quotas argue that women elected via quotas are not always the most qualified candidates; the quotas may displace qualified men; and the quotas are not compatible with meritocratic principles and incentives. However, despite the years of debate, exactly how gender quotas affect the competence of elected officials – whether women or men – has rarely been studied.

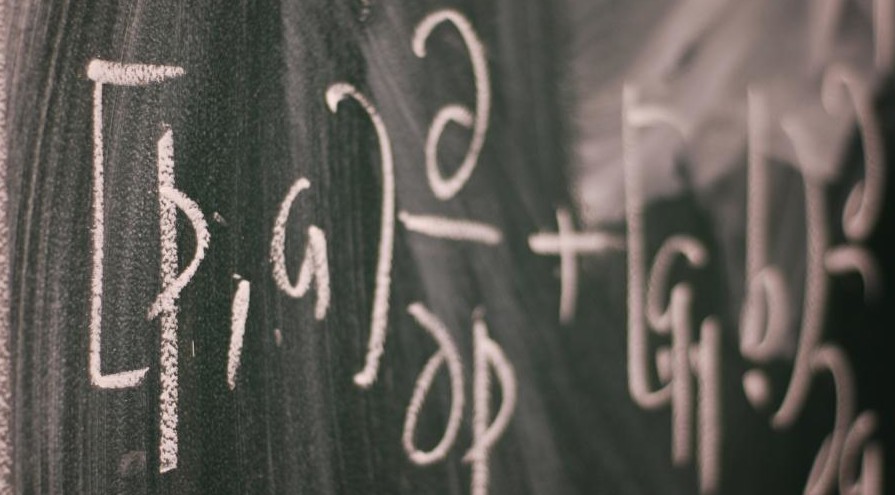

Studying advanced mathematics: the potential boost to women’s career prospects

Why are there so few women in highly paid careers as chief executives and, more generally, in finance, business, science, technology, engineering and mathematics? Analysing Danish data on young people whose educational and professional lives have been tracked over two decades since they started high school, this research suggests that part of the reason lies in restrictive bundling of courses, which deters talented young women from acquiring advanced mathematical skills. Changing the learning environment and designing the curriculum to identify and foster young women with high mathematical abilities would attract more of them and help to reduce the gender pay gap.