Summary

Do school meal programs lead to long-term economic benefits for pupils and reduce inequality in economic outcomes? This research analyzes the impact of a reform that introduced nutritious school lunches, free of charge, for all pupils in Swedish primary schools. The Swedish case is especially suitable for measuring income gains in later life. The results suggest that the reform led to long-term economic benefits for the relevant pupils, which greatly outweighed the costs. Pupils from poorer families gained the most.

It is well established that targeted policies, designed to improve early life conditions, can have important long-run benefits. Much less is known about the effects of universal policies that improve health and nutrition during the “middle” period between birth and adulthood. School meal programs are especially interesting in this regard, since it is widely believed that the school-age years form an important developmental period for the intake of diets of high nutritional quality, and a large share of children can be reached at schools at low cost.

In the new research summarized here, the authors show that such programs can have substantial long-term benefits. They analyze the impact of the Swedish school lunch reform that was gradually rolled out in the 1950s and 1960s, and which was explicitly designed to provide more nutritious meals. On average, pupils exposed to the program during their entire primary schooling have three percent higher lifetime earnings, compared to unexposed pupils. The income gains were higher for pupils from poor households, suggesting that the program reduced socioeconomic inequalities in adulthood.

Exposure to the school lunch program also had substantial effects on educational attainment and health. When taking into account the costs and benefits over a long period of time, the discounted benefits were four times higher than the discounted costs, indicating major societal gains from the program. A broader conception of the program benefits would be likely to yield even higher figures for the benefits relative to the costs. The Swedish case, given its scale and design, provides a unique opportunity to understand the potential gains from improved school lunches in other countries, and suggests these gains may well be substantial.

Main article

A large literature shows that targeted policies that improve early life conditions can have important long-run benefits. Much less is known about the long-run effects of universal policies that improve health and nutrition during the “middle” period between birth and adulthood. School meal programs are particularly interesting in this regard, since it is widely believed that the school-age years form an important developmental period for the intake of diets of high nutritional quality, and a large share of children can be reached at schools at low cost. The research summarized here confirms that better nutrition at school has long-run benefits which greatly outweigh the costs of provision. The benefits are largest for poorer households, helping to lower inequality.

Although school meal programs have been around since the 1940s in countries such as Finland, Sweden, the UK, and the US, they have been difficult to evaluate. The US school lunch program, for instance, is federal: hence there is little variation across areas, and quasi-experimental approaches to measuring the effects are not easily applied (Hoynes and Schanzenbach 2015). The lack of evidence can be seen in how different countries adopt vastly different school meal policies. Estonia, Finland, and Sweden have long served nutritious school lunches to all pupils free of charge, while children in neighboring countries, such as Norway and Denmark, bring their own packed lunch to school. Britain, France, and Italy serve school lunches according to nutritional standards, but the meals are means tested and come at a cost for most families. Storcksdieck et al. (2014) describe school lunch policies in Europe in more detail.

The small number of previous quasi-experimental studies analyzing the short-term impact of school-meal programs commonly find positive effects. For example, Belot and James (2011) study a program that improved nutritional standards of school lunches in the UK, and found benefits for short-term educational outcomes. Anderson et al. (2018) find positive short-term effects for students at public schools in California who had contracts with “healthy” school vendors.

The only previous study that evaluates the long-term impact of school lunch provision is Hinrichs (2010). He uses a change in the funding formula for the National School Lunch Program (NSLP) in the US, and finds large and positive effects on educational attainment, but his paper evaluates the effect of the NSLP before the 1995 nutritional guidelines were introduced. No previous study has estimated the long-term impact of a policy that introduces school lunches with strictly controlled nutritional quality. Perhaps the closest is Butikofer et al. (2018), who analyzed the long-term economic benefits of a program that replaced a hot meal at the end of the school day with a nutritious breakfast for children with special needs for extra nutrition, in urban municipalities in Norway in the 1920s.

In the research summarized here, we analyze the long-run effects of a school lunch reform in Sweden. The government introduced state subsidies for municipalities that introduced nutritious school lunches, free of charge for all pupils in primary school. We ask whether the rollout of the policy between 1959 and 1969 improved children’s economic, educational, and health outcomes throughout life. In addition, we ask whether certain groups benefited more than others.

The Swedish School Lunch Reform

The reform responded to a series of studies documenting the poor nutritional standard of the food consumed in the Swedish population. The reform proposal stressed that raising the nutritional standard for children was especially important, and providing nutritious school lunches in primary school was thought to be the most effective way to achieve this.

Under the new scheme, the school lunch would be freshly cooked hot food with adequate micronutrients, together with milk and bread. Detailed guidelines were provided by the National Medical Board regarding the amounts of vitamins A, B, and C, protein, calcium, iron, and phosphorus. The meals were to provide a third of the daily need for calories, or more than 800 calories. To implement this, the schools were provided with three-week school lunch menus: often meat-based stews, vegetable-based soups, fish and meat or egg-based dishes, and fruit, berry, or vegetable-based dishes. Figure 1 shows an example of such a three-week menu. With each lunch, 30 cl milk and rye bread with butter were to be served.

The reform included substantial support to the municipalities that introduced the school lunches. The National School Board provided guidance on how best to organize the lunches, by actively visiting schools and providing information on nutritious ingredients, and by providing education programs for kitchen staff.

The students’ exposure to the program depended on which grade they were in when the program was introduced, and ranged from zero to nine years. Swedish children start primary school at age seven. This feature of the reform means we can examine how the outcomes studied vary with the intensity of exposure.

Did Nutritional Quality Increase?

Surveys conducted before the school lunch reform suggest that about two-thirds of the pupils had a lunch meal consisting of milk and cheese sandwiches brought from home. For most pupils, the school lunch reform thus added a hot nutritious meal to the typical pre-reform milk and bread/sandwich packed lunch.

When we compare the nutritional content of the typical packed lunch with the new school lunches, the latter clearly represented a positive nutritional “shock”. The largest changes were found for iron, increasing from 0.588 mg to 7 mg per meal, and for vitamin C, which increased from 1.2 mg to 25 mg. The changes were also large for vitamin A, which increased fourfold, and for protein, phosphorus, and vitamin B, where intake doubled. The only nutritional component that did not change was calcium. For these calculations, we used the Swedish Food Agency’s Swedish Food Composition Database.

Data and Empirical Design

We analyze the impact of the reform by using newly-collected historical data from the Swedish National Archive, on its gradual implementation across municipalities in Sweden between the years 1959 and 1969. During this period, 265 municipalities introduced the program, with a roughly equal number of municipalities joining each year. We have linked these historical data to administrative records that cover the population of primary school pupils: about 1.5 million pupils born between 1942 and 1965. The National Archive has not kept forms sent by the municipalities before 1959, and hence we lack information on year of adoption for municipalities that introduced the reform before 1959.

Our statistical analysis uses an approach called “difference-in-differences”, which essentially compares differences in changes in outcomes over time between pupils who were affected and those who were not. To be technical, we assume that exposure to school lunches is as good as random, conditional on birth cohort fixed effects and municipality fixed effects. That assumption is supported by a number of specification checks. Using this research design, we estimate the impact of the school lunch reform on a broad range of outcomes taken from income and education registers, the military enlistment register, the medical birth register, and hospitalization and mortality registers. Lifetime income is calculated by summing up annual income between 1968 and 2011, after adjusting for inflation.

All Pupils Gained from the Reform

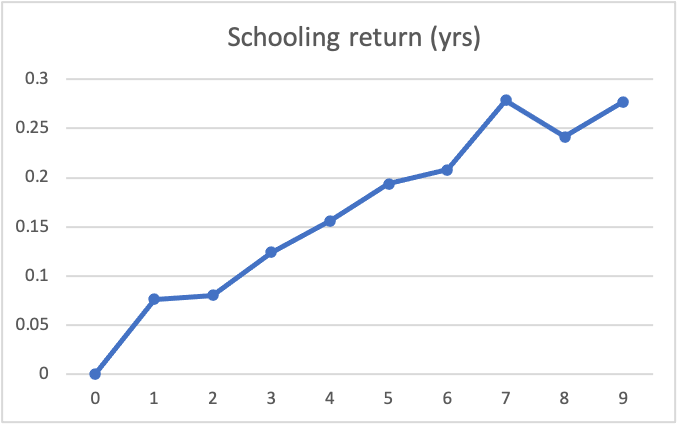

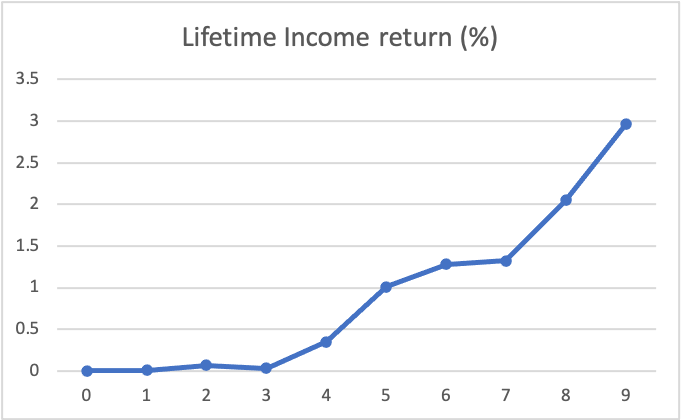

Our first result provides evidence that the reform led to improved nutrition: both male and female pupils exposed to the program became significantly taller. Similar positive effects were also found on years of schooling and university attendance. Figure 2 shows that male and female pupils exposed to the school lunch program for nine years – hence, during their entire primary schooling – became about 0.8 and 0.6 centimeters taller, respectively, and obtained 0.3 more years of schooling.

Figure 2. The effect of year of exposure to school lunches on height, schooling, and lifetime income

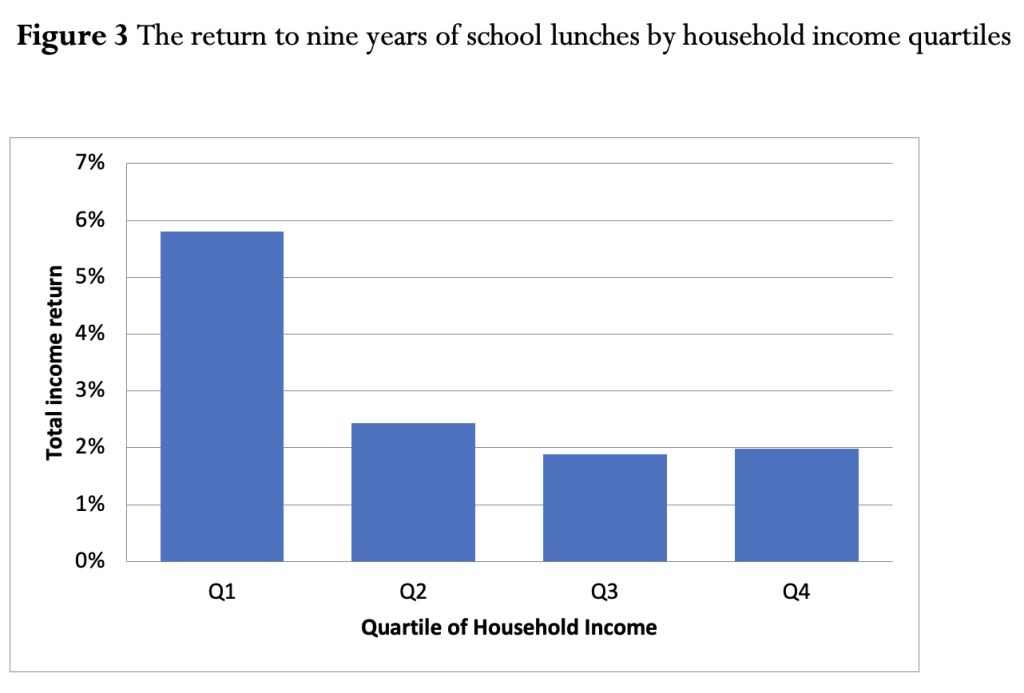

The program also had substantial long-term benefits for income: pupils exposed during their entire primary schooling had three percent greater lifetime income compared to unexposed pupils (Figure 2). We also find interesting heterogeneity in the effects, where children from poor households benefit the most, although children from all households benefit to some extent. Pupils from poor households gained six percent greater lifetime income compared to unexposed pupils, whereas other pupils gained about two percent greater lifetime income (Figure 3). Under reasonable assumptions, our results also suggest that height improvements, together with increased schooling, can explain a large part of the effect of school lunches on lifetime income.

We find no long-term effects on mortality, morbidity, sick leave, and disability, or on health outcomes of children in the second generation, however. This tallies with our finding that the positive effect of the program on income is largest up to the mid-30s, and then gradually declines.

Can Alternative Mechanisms Explain the Results?

Besides improving nutrition, another key motivation behind the school lunch program was to ease the burden on mothers – who were often responsible for providing packed lunches for their children – and encourage them to undertake paid work. The program may thus have improved both nutrition and household finances, through increased female labor supply. In addition, the program may have made it more attractive for some students to attend school.

To investigate the latter mechanism, we collected and digitized data on school absence from municipality archives in Sweden and show that the school lunch reform did not lead to any changes in school attendance rates, which were already high before the reform. In addition, we show that the reform led to small increases in parental labor supply and household income, but these were too small to explain the effect on the children’s lifetime income. We therefore believe that a reasonable interpretation of our results is that pupils, when eating a nutritious lunch every day, became better equipped to absorb the material presented in school. This aligns with the results in Belot and James (2011), where test scores among eleven-year-olds increased already within the first year after the introduction of nutritious meals.

Did the Benefits Outweigh the Costs?

Our estimates suggest that nine years of school lunches increase lifetime earnings by about SEK 102,000 (EUR 1,020), discounting future earnings at a three percent interest rate and counting earnings from age twenty-one to sixty-five. This is almost four times the total discounted cost of the program, which includes both the cost of the food and the facilities and equipment needed. If we instead focus on children in poor families (in the bottom quartile of household income), the benefit-cost ratio increases substantially: the discounted benefits were seven times larger than the discounted costs. These are back-of-the-envelope calculations that count only the income benefits of the school lunch program. The benefit-cost ratio would be likely to be even more favorable when counting the other gains of the program.

Conclusion

The Swedish school lunch program had substantial long-term economic benefits, with a benefit-to-cost ratio about twice that of the US Head Start program (Kline and Walters 2016). The ratio for children from the poorest quartile of households is even larger, and in the same ballpark as those reported for highly selective welfare programs, such as the Perry Preschool Project, which targeted children below the age of five from very disadvantaged backgrounds (Heckman et al. 2010).

Our results are relevant for Western countries today, even though the school lunch program was rolled out during the 1950s and 1960s. The program was introduced in a wealthy country, where the main problem was that parents lacked knowledge about healthy food habits. Hence, the results should be informative for other developed countries that plan to improve, or have improved, the nutritional content of the food served in schools. The nutritional standards of the Swedish school lunch program are similar to those in more recent school meal programs, such as the “School Meals Initiative for Healthy Children” in the US. Given the nature of the data, the Swedish school lunch reform is a unique opportunity to learn about the potential long-term benefits of recent school meal initiatives elsewhere.

This article summarizes “Long-Term Effects of Childhood Nutrition: Evidence from a School Lunch Reform” by Petter Lundborg, Dan-Olof Rooth, and Jesper Alex-Petersen, published in the Review of Economic Studies in March 2022.

Petter Lundborg is at the Department of Economics, Lund University. Dan-Olof Rooth is at the Swedish Institute for Social Research, Stockholm University. Jesper Alex-Petersen is at the Department of Clinical Sciences, Lund University.