Summary

Standard models of the labor market assume that workers have accurate beliefs about the differences in wages across firms, but this fundamental assumption remains broadly untested. This paper assesses the accuracy of workers’ beliefs about their outside options and explores the consequences of potential misperceptions.

To test the accuracy of worker beliefs, a representative survey was embedded in the German Socio-Economic Panel (SOEP), which was linked to German administrative matched employer-employee data. We asked each employed respondent about wages in the external labor market and the expected wage change that would accompany a switch to their next-best employer—their outside option. We then compare these expected wages against objective benchmarks on this outside option.

In a stark rejection of the assumption of accurate beliefs, workers appear to anchor their beliefs about wages with other employers on their current wage: workers believe their outside option is much closer to their current wage than it actually is—a phenomenon we dub anchoring. Additional results indicate that respondents also anchor beliefs about wage changes of coworkers who move out of the firm and the external wage distribution in their occupation. Overall, our results are consistent with a model in which workers hold incorrect and imprecise beliefs about the external wage distribution, and strongly rely on their current wage as a signal for their outside option.

These findings raise the possibility that workers’ misperceptions may affect the allocation of workers to firms, keeping some workers in low-wage firms who would, if given correct information, search and leave their employer. Indeed, we find that workers in low-wage firms are too pessimistic about the labor market.

To causally identify the anchoring mechanism and explore its effects on labor market behavior, we carry out an online information experiment. We provide a random subset of respondents with information about the average wage of workers with similar characteristics to the respondent in the same labor market. Results indicate that the workers in this treatment group use the provided information to correct not only their beliefs about the wages of similar workers, but also their beliefs about their own outside options. Furthermore, this updating of beliefs causes them to adjust their job search and wage negotiation intentions. A 10ppt increase in beliefs about the wage at the outside option raises the respondent’s stated probability of quitting their current job by 2.6ppt (SE 0.87).

To explore the aggregate consequences of anchoring, we build a simple equilibrium model of the labor market that is consistent with our empirical findings. One worker type holds accurate beliefs while the other exhibits anchoring. In this model, anchoring acts as a source of labor market imperfections and can lead to the unraveling of the competitive, single-wage equilibrium and give rise to a segmented labor market equilibrium with a high- and a low-wage sector. Anchored beliefs keep overly pessimistic workers stuck in low-wage jobs, which gives rise to monopsony power and labor market segmentation.

These findings suggest anchoring and misperceptions about the wage distribution can be a source of labor market imperfections. This sort of misperception-based friction may result in similar phenomena as conventional frictions (e.g., search frictions), including a finitely elastic labor supply curve, but it has different policy implications. Possible policy remedies for wage distribution misperceptions include pay transparency mandates, minimum wages, sectoral bargaining, and—as illustrated in this paper—providing wage information about fine-grained labor market cells.

Main article

Standard labor market models assume that workers hold accurate beliefs about the external wage distribution, and hence their outside options with other employers. We test this assumption by comparing German workers’ beliefs about outside options with objective benchmarks. We find that workers wrongly anchor their beliefs on their current wage: workers that would experience a 10% wage increase if switching to their outside option only expect a 1% increase. Workers in low-paying firms are particularly likely to underestimate wages elsewhere. A simple equilibrium model indicates that anchored beliefs keep overly pessimistic workers stuck in low-wage jobs, which gives rise to monopsony power and labor market segmentation. However, our findings suggest that workers do correct their beliefs about their outside options when provided with accurate information about the wages of similar workers, and change their job search and wage negotiation intentions accordingly.

Firms differ substantially in the wages they pay to similar workers. Standard models of the labor market assume that workers have accurate beliefs about the differences in wages across firms, including in bargaining models and wage posting models with search. While this fundamental assumption remains untested, its violation—in the form of worker misperceptions about the wage distribution—could lead to worker misallocation and act as a source of monopsony power. For instance, Robinson (1933) writes:

“There may be a certain number of workers in the immediate neighbourhood and to attract those from further afield it may be necessary to pay a wage equal to what they can earn near home plus their fares to and fro; or there may be workers attached to the firm by preference or custom and to attract others it may be necessary to pay a higher wage. Or ignorance may prevent workers from moving from one to another in response to differences in the wages offered by the different firms.” (Our emphasis.)

Standard models of the labor market assume that workers have accurate beliefs about the differences in wages across firms

In our paper (Jäger, Roth, Roussille, and Schoefer, 2024), we assess the accuracy of workers’ beliefs about their outside options and explore the consequences of potential misperceptions. We cast the object of interest as the wage change (in percent) the worker would expect if forced to switch to the outside option, i.e., the next-best or average expected employer the worker would move to if she had to leave her current job. Hence, by studying outside options with other employers, our research complements work by Cullen and Pakzad-Hurson (2023) on within-firm wage differences and misperceptions thereof.

Research design: anchoring of beliefs about outside options

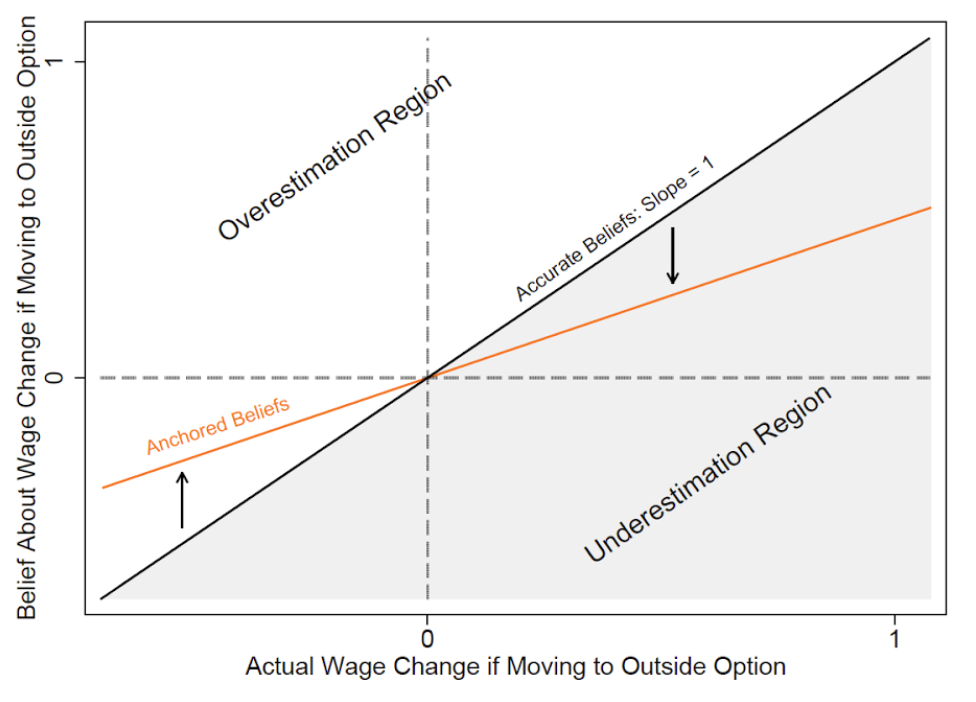

Figure 1 illustrates our research design, which tests the accuracy of workers’ beliefs about their outside option in the labor market. The x-axis represents the objective wage change if workers were forced to switch to the outside option, whereas the y-axis represents the subjective wage change, i.e., workers’ beliefs. The canonical benchmark of accurate beliefs about outside options would manifest itself as observations on the 45-degree line. Virtually all search and matching models implicitly assume this accuracy benchmark. Deviations from the accuracy benchmark can take two forms. Observations above the 45-degree line correspond to overestimation, i.e., workers expect an unrealistically large wage gain. Conversely, observations below the 45-degree line would imply that workers underestimate wages elsewhere.

We highlight a specific violation of the benchmark of accurate beliefs that we dub anchoring: workers believe their outside option pays a wage closer to their current wage than it actually does, i.e., they anchor their belief about their outside option on the current wage.

Figure 1: Research Design

Notes: This figure illustrates our research design. The y-axis depicts beliefs about wage changes if moving to the outside option, while the x-axis shows actual wage changes if moving. The black line illustrates the baseline case where workers hold beliefs that are accurate. Workers above (below) that line overestimate (underestimate) their outside option. The orange line has a slope that is less than 1, as would emerge if workers anchor their beliefs about their outside option on their current wages. Source: Jäger, Roth, Roussille, and Schoefer (2024).

Workers appear to anchor their beliefs about wages with other employers on their current wage

Empirical implementation in matched survey-administrative labor market data

To implement this research design, we conduct a representative survey embedded in the German Socio-Economic Panel (SOEP), which asks each employed respondent about wages in the external labor market and the expected wage change that would accompany a switch to their next-best employer—their outside option. We compare these beliefs with proxies for actual outside options, which we construct using administrative matched employer-employee data.

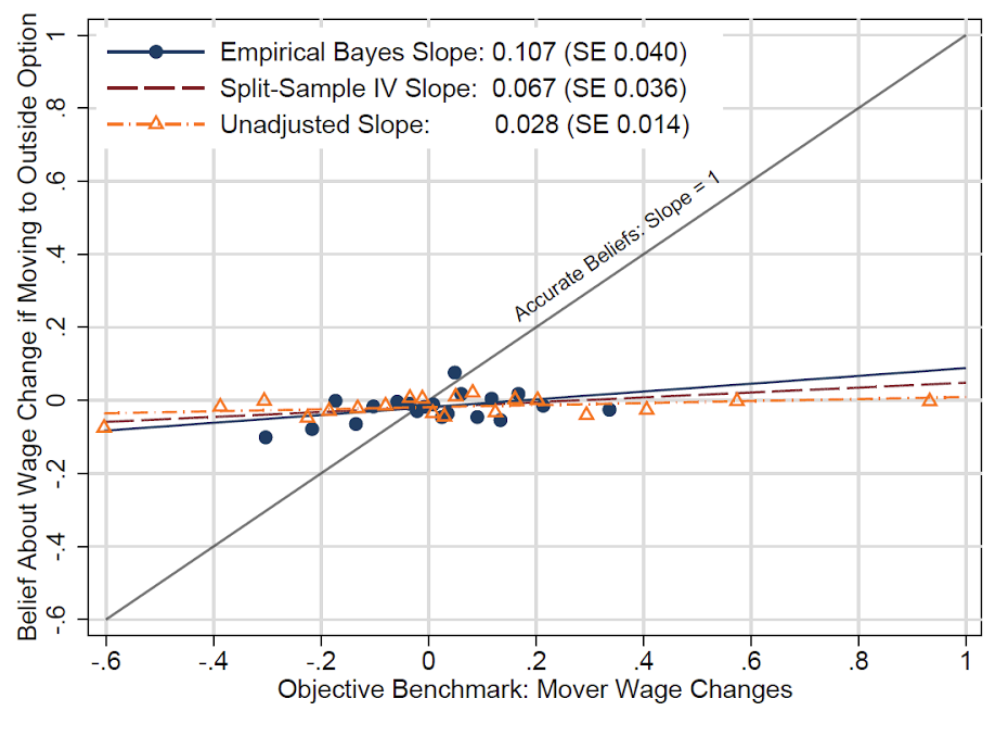

Figure 2 is the empirical analog of Figure 1 above, and reports our first result. It plots workers’ beliefs about the wage change they state they expect to receive if forced to leave their employer and switch to another one against objective benchmarks for this measure of outside option. Our main benchmark draws on realized wage changes of respondents’ coworkers who involuntarily left their firm. To approximate involuntary moves, we draw on employer switches with at least a brief unemployment spell. (We also use several methods to address measurement error and to isolate factors common to a firm’s workforce. Our benchmark specification uses an Empirical Bayes shrinkage procedure of coworker wage changes, and we also provide robustness checks with split-sample IV measurement error correction. As a complement to the coworker-based benchmark, we employ a machine-learning prediction trained on all involuntary separations in the administrative data to construct a benchmark that uses a richer set of predictors than the respondent’s current firm.)

Figure 2: Beliefs About Wage Change if Moving to Outside Option vs. Objective Benchmarks

Panel (a): Benchmark: Wage Changes of Coworkers Involuntarily Leaving Firm

Panel (b): Benchmark: Machine Learning Prediction

Notes: This figure presents binned scatter plots of SOEP 2019 respondents’ beliefs about their own wage change if forced to leave their firm against two objective benchmarks for the actual wage changes they would experience. In Panel (a), the benchmark is the mean log wage changes experienced by workers who left the SOEP respondent’s firm in the past 5 years (between 2015 and 2019). To narrow our attention to “involuntary”’ separations, we restrict the dataset to movers working full-time both before and after the move, and to movers who experience an intermediate unemployment spell before finding their next job. In Panel (b), the benchmark is based on machine learning for the wage changes SOEP respondents would experience if leaving their firm, with a model trained on the universe of “involuntary” moves in the German labor market (“involuntary” defined as above). The machine learning methodology is fully described in the paper. Source: Jäger, Roth, Roussille, and Schoefer (2024).

Workers that would experience a 10% wage increase if switching to their outside option only expect a 1% increase.

Workers’ expectations for their own wage change are tightly compressed around zero—even for workers in firms where coworkers systematically experience large wage changes upon leaving. We estimate a slope of 0.107 (SE 0.040) between predicted own wage changes and actual coworker wage changes. Similarly, we find slopes around 0.1 with the machine learning benchmark and a series of robustness checks. Anchoring also emerges with narrower definitions of coworker wage changes, for instance, focusing on coworkers with the same occupation or education level.

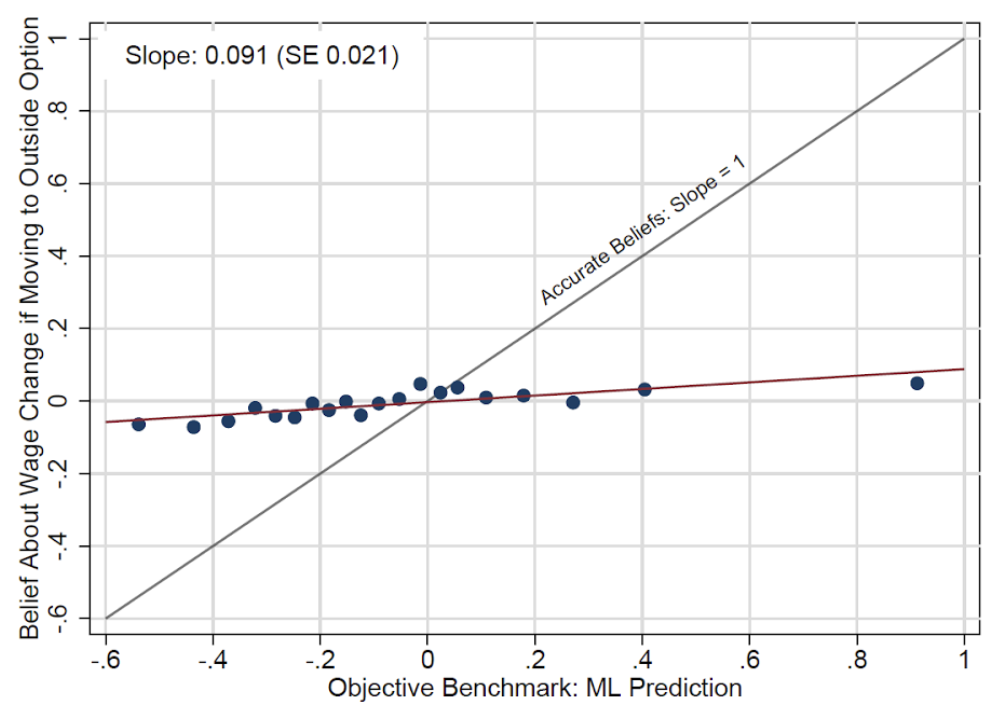

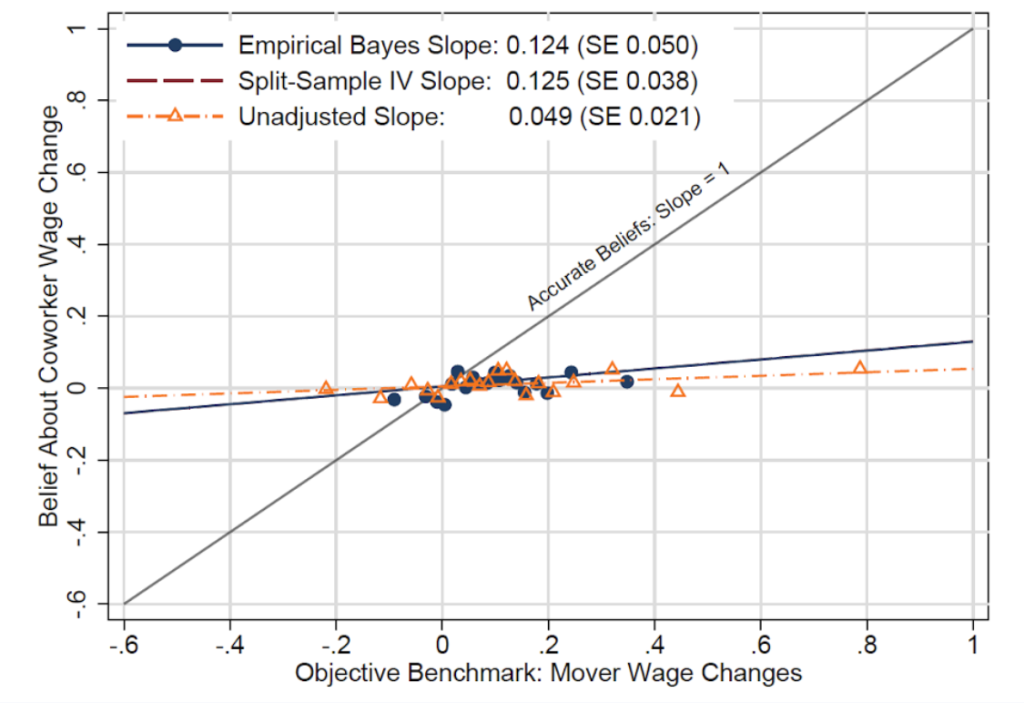

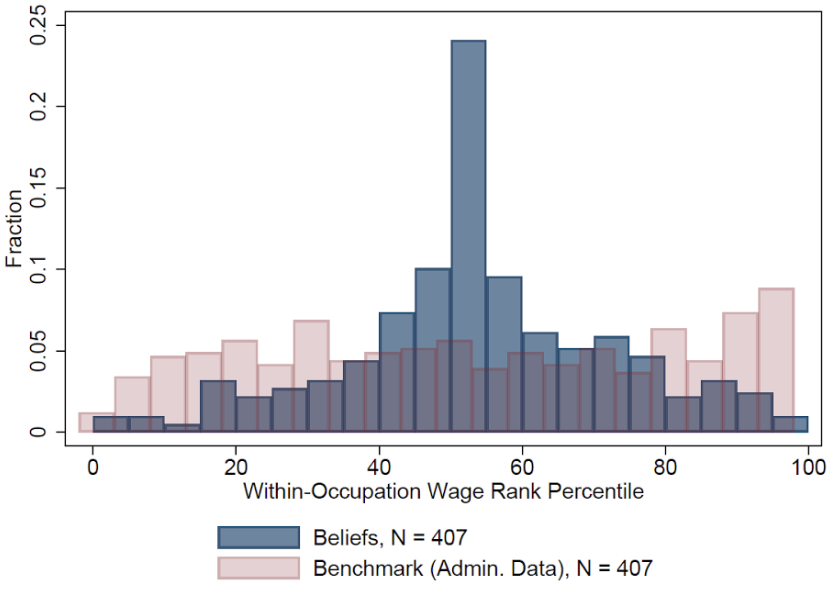

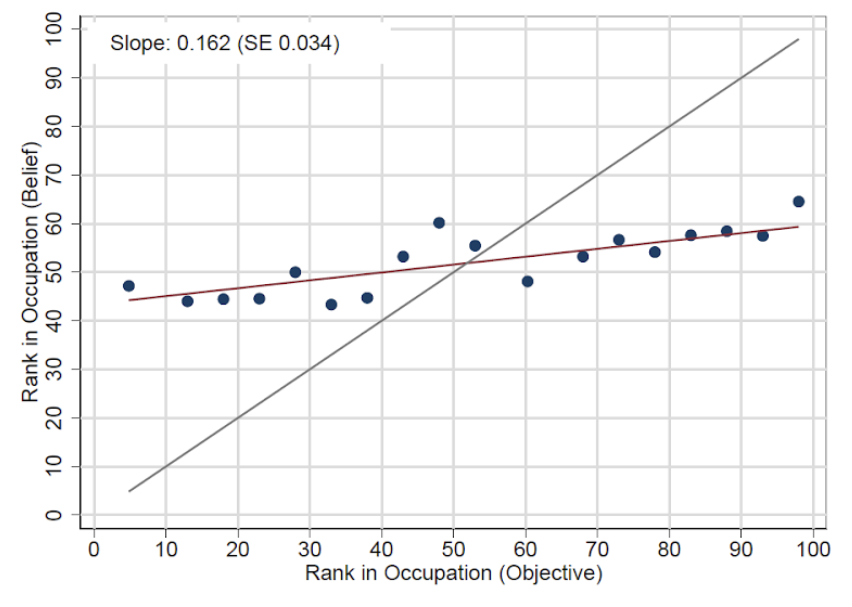

This slope between beliefs and actual outside options is far from the benchmark slope of one that would represent accurate beliefs. It is closer to zero, as would emerge if workers’ beliefs were anchored on their current wages and unresponsive to actual outside options. In line with anchoring, we also find that respondents anchor beliefs about wage changes of coworkers who move out of the firm and the external wage distribution in their occupation, both of which we can directly compare to their empirical counterparts in the administrative data. Figure 3 shows the results for the coworkers’ actual wage changes, and Figure 4 shows these results for the rank of the individual’s pay within the labor-market-wide wage distribution for their occupation. Overall, our results are consistent with a model in which workers hold incorrect and imprecise beliefs about the statistical properties of the external wage distribution, and strongly rely on their current wage as a signal for their outside option.

Figure 3: Beliefs About Mover Wage Changes vs. Actual Mover Wage Changes

Notes: This figure presents binned scatter plots of SOEP 2019 respondents’ beliefs about the typical wage of co-workers who left their firm between 2015 and 2019. It is analogous to Figure 2 Panel (a), except that the y-axis reports beliefs about the typical wage change of co-workers (irrespective of whether voluntary or involuntary), and the x-axis is the corresponding objective benchmark (but now calculated from all co-worker moves rather involuntary ones only, consistent with this survey question). Source: Jäger, Roth, Roussille, and Schoefer (2024).

Figure 4: Beliefs About Own Wage Rank in Occupation

Panel (a): Benchmark: Wage Changes of Coworkers Involuntarily Leaving Firm

Panel (b): Benchmark: Machine Learning Prediction

Notes: This figure tests the accuracy of 2019 SOEP respondents’ beliefs about their wage rank within their occupation (compared to workers in other firms). Panel (a) shows a histogram of beliefs as well as the actual ranks of our respondents (the latter calculated at the 4-digit occupation level in our administrative data sample in 2019). Panel (b) shows a binned scatter plot of beliefs against actual rank, along with a regression line. Source: Jäger, Roth, Roussille, and Schoefer (2024).

These findings raise the possibility that workers’ misperceptions may affect the allocation of workers to firms, and specifically keep some workers in low-wage firms who would, if given correct information, search and leave their employer. Indeed, we find that workers in low-wage firms (e.g., with low AKM (Abowd, Kramarz, and Margolis, 1999) firm fixed effects) are too pessimistic about the labor market. Workers at the 25th percentile of the firm AKM effect distribution, for example, underestimate their outside option by about 10ppt. Similar patterns emerge for the external wage distribution: workers in low-wage firms underestimate both the wage changes of coworkers moving to other firms and the median wage in their occupation, and overestimate their rank in their occupation’s wage distribution. These patterns could plausibly be caused by misperceptions of outside options as worker beliefs are correlated with intended search and bargaining behavior.

Misperceptions may affect the allocation of workers to firms.

Towards a causal test: information experiment and de-anchoring

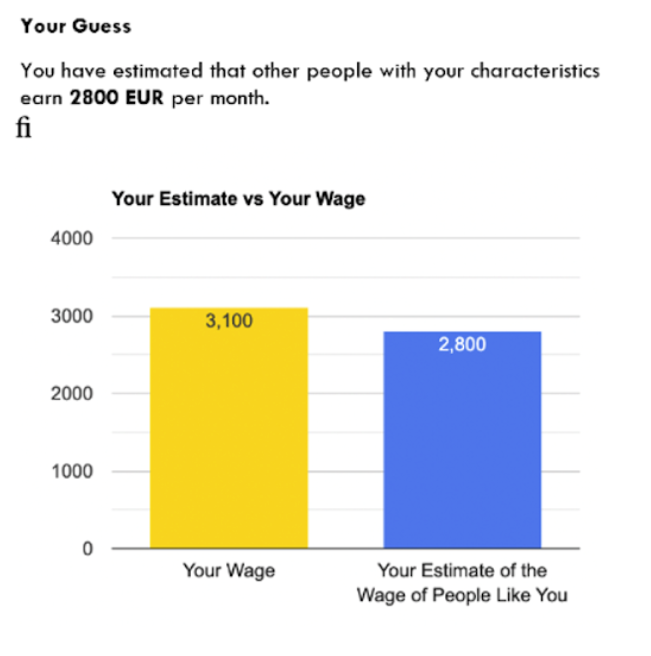

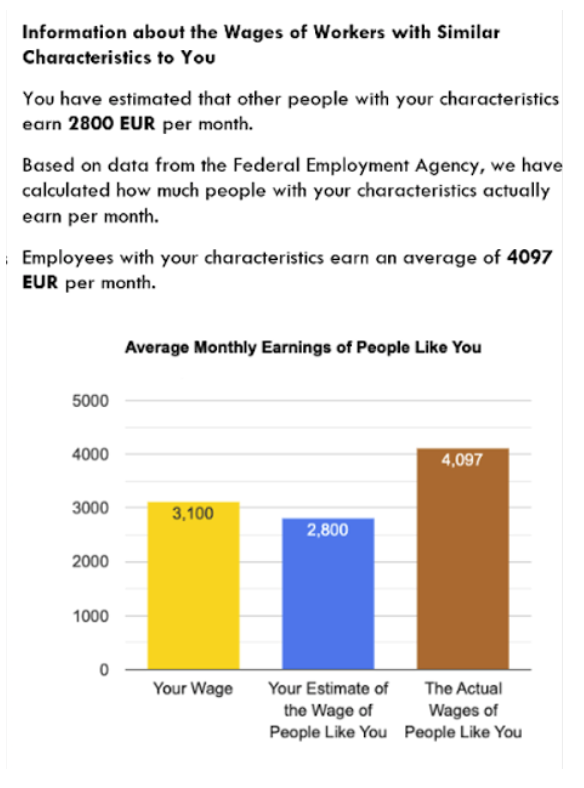

To causally identify the anchoring mechanism and explore its effects on labor market behavior, we implement an additional research design in the form of an online information experiment in Germany. We provide a random subset of respondents with information about the average wage of workers with similar characteristics in the same labor market. Figure 5 shows the treatment and control screens.

Figure 5: Experiment: Information Treatment Screen

Panel (a): Control Group

Panel (b): Treatment Group

Notes: These panels display (a translated version of) the information screen for a respondent with the same characteristics, in either the control (Panel (a)) or the treatment group (Panel (b)). The respondent reports a monthly wage of 3,100 EUR and estimates that other people with their characteristics earn 2,800 EUR a month on average. These screens are preceded by a screen reminding the respondent of the list of characteristics they reported (gender, age, occupation, labor market region, education level, and so on) to explicitly identify the characteristics being held fixed. For the treatment group, the actual average wage is also displayed. Source: Jäger, Roth, Roussille, and Schoefer (2024).

Anchored beliefs keep overly pessimistic workers stuck in low-wage jobs, which gives rise to monopsony power and labor market segmentation.

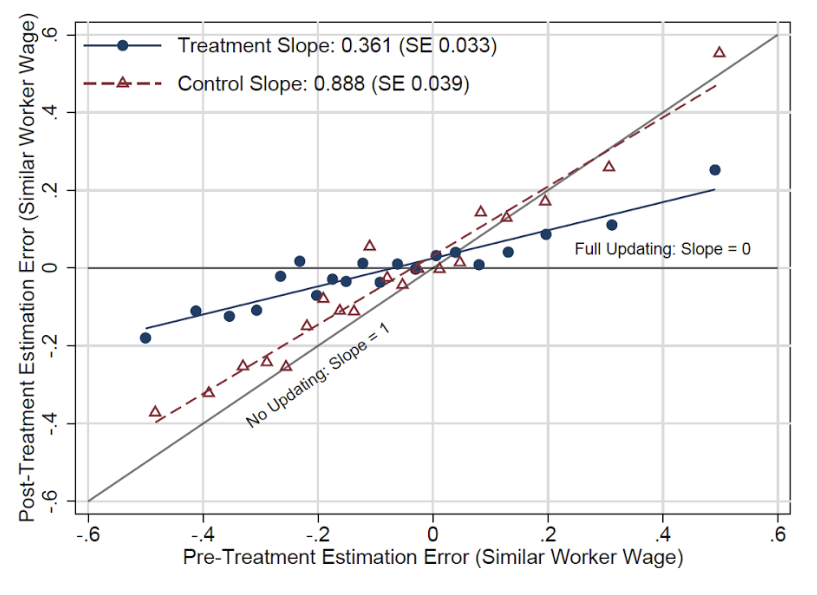

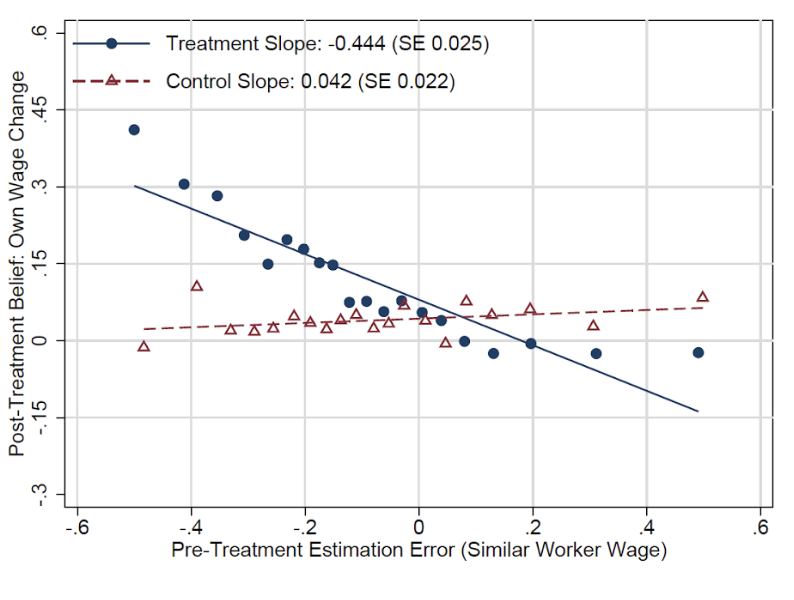

We find that treated workers use this information to correct not only their beliefs about the wages of similar workers, but also their beliefs about their own outside options. Figure 6 reports those results and is organized in the same way as Figures 1 to 4 above, except that the y-axes now denote post-treatment beliefs (errors compared to a benchmark and the level).

Figure 6: Effects of Information Treatment

Panel (a): Intervention Check: Beliefs about Wages of Similar Workers

Panel (b): First Stage: Beliefs about Outside Option

Notes: The figure presents binned scatter plots using data from our 2022 information experiment, in which the treatment group received information in the form of the average wage of workers with similar characteristics from the same labor market. As an intervention check, Panel (a) plots the post-treatment estimation error about that wage against the pre-treatment one, separately for the treatment and control groups. The estimation error is defined as the percentage difference between beliefs and the actual wage. Panel (b) plots participants’ beliefs about their outside option (wage change) against the pre-treatment estimation error. Source: Jäger, Roth, Roussille, and Schoefer (2024).

We then document that this updating of beliefs causes them to adjust their job search and wage negotiation intentions. A 10ppt increase in beliefs about the wage at the outside option raises the probability of quitting the current job by 2.6ppt (SE 0.87). This estimate suggests that correcting the misperceptions of workers at the 25th percentile of the AKM firm effect distribution would cause about a 2.6ppt—or 11%—increase in the number of those workers deciding to leave their firms. We caution that this experiment implements a light-touch treatment and studies effects on planned behaviors declared at the end of the online survey. While our experiment thus leaves the question of longer-term effects to future research, the causal effects of the information treatment do point to misperceptions as a source of labor market imperfections.

A growing body of evidence suggests that increases in between-firm pay transparency can redirect worker flows to higher-wage employers

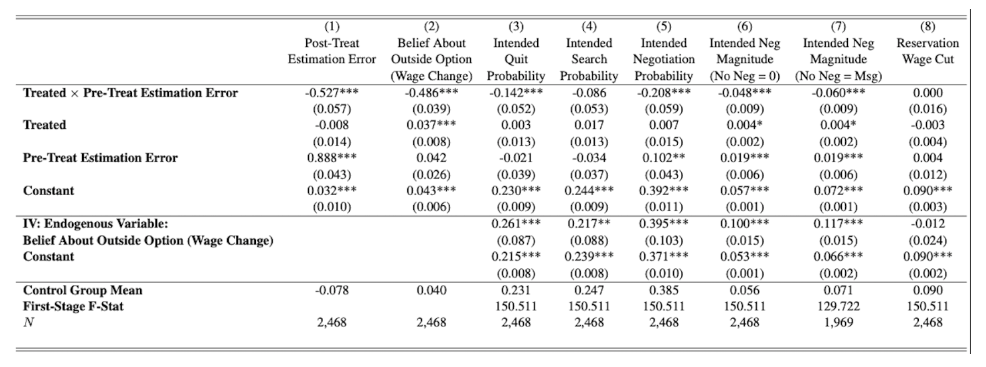

These results are reported in Table 1 below. Formally, we employ an instrumental variable (IV) regression that permits us to estimate the causal effect of the information treatment on labor market behavior through the channel of shifting workers’ beliefs. The endogenous variable is workers’ beliefs about their outside option. The instrument is the treatment indicator and its interaction with the initial estimation error, exploiting the heterogeneity in estimation error described above and plotted in Figure 6(a) above. Formally, we estimate the following model with 2SLS:

Table 1: Regression Results of Information Experiment

Notes: This table reports results of the information experiment in a 2022 online survey. It reports regressions of each outcome variable on the respondent’s pre-treatment estimation error about the mean wage of similar workers (in logs), a treatment indicator, and an interaction between the treatment indicator and pre-treatment estimation error. We also report IV specifications, using respondents’ beliefs about their outside option as the endogenous variable. In Column (1), the outcome is a post-treatment version of the estimation error, i.e., beliefs about wages of similar workers. In Column (2) the outcome is the respondent’s post-treatment belief about the wage change at their outside option. Columns (3)-(8) report results on intended labor market behaviors: probability of quitting, probability of finding another job, probability of negotiating for a raise, the expected magnitude of the raise asked (with no negotiations planned coded as a zero-magnitude raise or as missing), and the reservation wage as a percent of their current wage. Source: Jäger, Roth, Roussille, and Schoefer (2024).

Equilibrium implications: an equilibrium model of anchored beliefs and employer power

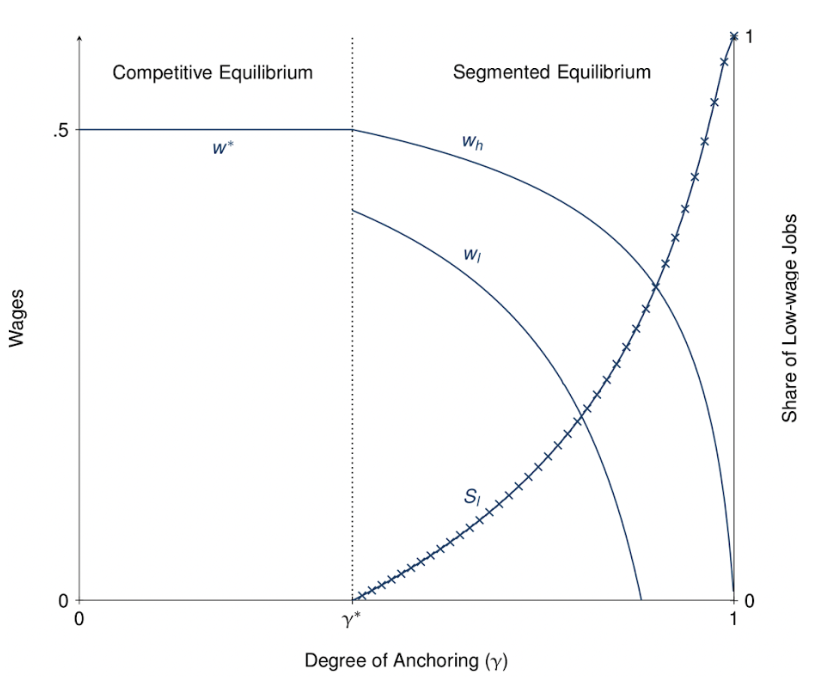

To explore aggregate consequences of anchoring, we build a simple equilibrium model of the labor market that is consistent with our empirical findings. In the model, one worker type holds accurate beliefs. The other type exhibits anchoring; these workers hold imprecise beliefs about the wage distribution, and hence use wages of current employers to form beliefs about outside options—and to decide whether to search. Workers with anchored beliefs therefore stay put in low-wage firms because they underestimate their outside options. Firms anticipate and can exploit these misperceptions. Anchoring acts as a source of labor market imperfections that the model would otherwise rationalize through standard search costs: anchoring can lead to the unraveling of the competitive, single-wage equilibrium and give rise to a segmented, or dual, labor market equilibrium with a high- and a low-wage sector. But it generates those patterns through an informational mechanism uniquely consistent with our empirical evidence and distinct from standard switching costs: workers who underestimate their outside options are concentrated in the low-wage sector, and would update beliefs and switching behavior when correcting their beliefs.

Figure 7 illustrates those effects. It plots equilibrium wages and the share of low-wage jobs as a function of the degree of anchoring γ (i.e., the weight workers put on their current wage when forming beliefs about their outside option). The dotted vertical line marks the cutoff value of anchoring that induces a switch from a competitive to a segmented labor market, with a high- and a low-wage sector.

Figure 7: Model-Based Analysis of Equilibrium Implications of Anchoring

Notes: The figure plots equilibrium wages and the share of low-wage jobs as a function of the degree of anchoring (i.e., the weight workers put on their current wage when forming beliefs about their outside option). The dotted vertical line marks the cutoff value of anchoring that induces a switch from a competitive labor market to a segmented labor market with a high- and low-wage sector. Source: Jäger, Roth, Roussille, and Schoefer (2024).

Implications for research and policy

Our findings suggest anchoring and misperceptions about the wage distribution can be a source of labor market imperfections. While such a misperception-based friction may result in similar phenomena (such as finitely elastic labor supply curves) as conventional frictions, it has distinctive predictions. For instance, in standard models with amenity differentiation or search frictions, workers are assumed to have perfect information about the wage distribution, their position therein, and hence their outside options; in those models, giving workers accurate information about the statistical properties of the wage distribution would change neither beliefs nor behavior. Both predictions are rejected by our evidence.

Why might the biases we document persist? On the worker side, perhaps privacy norms keep workers from sharing their wage information. On the employer side, firms may avoid advertising high entry wages, as—in the presence of fairness concerns between colleagues—they may wish to avoid antagonizing some incumbent workers or generating wage pressure. The behavioral industrial organization literature has explored rationales for firms to obfuscate product prices to consumers, and has documented evidence of consumers misperceiving prices and/or failing to optimize in their purchasing behavior. Our evidence for similar patterns among workers choosing between firms raises the possibility that broader lessons from behavioral industrial organization may carry over to labor markets. Our evidence also highlights the importance of work investigating the extent to which firms may exploit workers’ biases or may themselves be subject to imperfect information.

The presence of misperceptions also gives rise to distinct policy remedies, such as pay transparency mandates. Consistent with our findings, a growing body of evidence suggests that increases in between-firm pay transparency can redirect worker flows to higher-wage employers (Cullen, 2024). Besides pay transparency mandates, other labor market institutions, such as minimum wages or sectoral bargaining, may also reduce misperceptions. Our experimental evidence suggests that providing wage information about fine-grained labor market cells could serve as a promising tool to debias workers’ beliefs about outside options.

This article summarizes ‘Worker Beliefs About Outside Options’ by Simon Jäger, Christopher Roth, Nina Roussille, Benjamin Schoefer, published in The Quarterly Journal of Economics in August 2024.

Simon Jäger and Nina Roussille are at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), Christopher Roth is at the University of Cologne, and Benjamin Schoefer is at the University of California, Berkeley.

References:

Abowd, J.M., Kramarz, F. and Margolis, D.N., 1999. High wage workers and high wage firms. Econometrica, 67(2), pp.251-333.

Cullen, Z., 2024. Is pay transparency good?. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 38(1), pp.153-180.

Cullen, Z.B. and Pakzad‐Hurson, B., 2023. Equilibrium effects of pay transparency. Econometrica, 91(3), pp.765-802.

Jäger, S., Roth, C., Roussille, N. and Schoefer, B., 2024. Worker Beliefs About Outside Options. The Quarterly Journal of Economics.

Robinson, Joan. 1933. The Economics of Imperfect Competition. Macmillan.