Summary

Many cities use centralized school choice systems to assign students to schools. In centralized choice, students submit ranked lists of schools to a centralized authority, who places each student in at most one school.

The first policy challenge we consider is how districts should design the assignment mechanism, which is the procedure that takes submitted applications and makes assignments. Two systems are currently widely used. The “Boston” Mechanism gives applicants an admissions advantage at schools they place higher on their lists, which means they may need to balance their preferences with their chance of admission when they are ranking schools. In contrast, the Deferred Acceptance Mechanism (DA) is strategyproof in that it does not provide any advantage to candidates based on submitted rank; the best approach is just to list the schools you like, in the order you like them.

In Kapor, Neilson, and Zimmerman (2020), we combine administrative data with survey data from households in New Haven that were participating in school choice under the “Boston” Mechanism. We show that these families engage in strategic behavior, but often on the basis of inaccurate information. To get at how important these belief errors are in practice, we formulate a model of school choice. We show that, given the belief errors we see, the easier-to-use DA mechanism outperforms the potentially more expressive Boston mechanism. We also find that this conclusion would be reversed if a policymaker could somehow eliminate belief errors. The key takeaway is that once one accounts for mistakes that families make when participating in school choice, approaches to school choice mechanism design that make things simpler for parents seem more appealing from the perspective of student welfare.

Arteaga et al. (2022) goes on to examine the strong assumption that applicants actually know their own preferences. We find that families generally have limited knowledge of nearby schooling options, and some have wildly inaccurate beliefs about their admissions chances. The interaction of these factors can mean that families stop their school search prematurely because they incorrectly think they are going to be placed in a school. We designed a treatment that warned Chilean applicants submitting risky applications that they were at substantial risk of nonplacement. Around 22% of applicants that received this warning added at least one school to their application, reducing nonplacement risk by 58%.

Together, these papers provide practical, evidence-driven guidance for districts trying to both make school choice easier for families and help students match to schools they like. Beyond the specific results, an important feature of this research is that it has produced sustained and scaled policy change. New Haven and Chile continue to employ the mechanism design and choice support policies discussed here, and a number of other countries either have adopted or are in the process of adopting similar approaches. The close collaboration between researchers, policymakers, and implementation partners that made this work possible may be a useful approach for conducting scalable interventions in other domains.

Main article

Kapor et al. (2020) and Arteaga et al. (2022) show that participants in school choice mechanisms are sophisticated strategic actors trying to make the best choices, but with limited information about both the schools they are choosing from and the process itself. Policymakers can help mitigate these frictions in two ways. They can use assignment mechanisms that reduce the need for informed strategic play inside the centralized system, and they can build mechanisms to help families with strategic decisions that remain outside this system (e.g., school search). This research has produced sustained and scaled policy change, and the collaborative approach used may also be useful in conducting scalable interventions in other domains.

Many cities use centralized school choice systems to assign students to schools. In centralized choice, students submit ranked lists of schools to a centralized authority. The authority then uses some combination of priorities (e.g., test scores or neighborhoods) and random tiebreakers to place each student in at most one school.

Participants in school choice mechanisms are sophisticated strategic actors trying to make the best choices with limited information

Centralized choice systems help alleviate congestion—cases in which some students receive multiple offers and spots at desirable schools go unfilled. But they also create challenges for parents and students trying to navigate the choice process and find schools they like. In particular, applicants may struggle to identify good matches from a potentially large number of options, and they may not know how best to fill out their application to get a school they like from amongst the schools they know about.

In two related papers—Kapor, Neilson, and Zimmerman (2020), and Arteaga, Kapor, Neilson, and Zimmerman (2022)—we document the challenges that families face when participating in school choice. We then provide practical, evidence-driven guidance for districts trying to both make school choice easier for these families and help students match to schools they like more.

Mechanism design with information frictions

The first policy challenge we consider is how districts should design the assignment mechanism, which is the procedure that takes submitted applications and makes assignments. Two commonly used assignment mechanisms place very different informational demands on families. The “Boston” Mechanism, used in cities including Seattle and Barcelona, gives applicants an admissions advantage at schools they place higher on their lists. This means that the top spot on an application is valuable real estate. Applicants may not want to list their most-preferred school first if their chances of admission are low. Instead, they may want to list a school they like less but where a first-place ranking guarantees admission. In contrast, the Deferred Acceptance Mechanism (DA)—used in New York, among others—is strategyproof. It does not provide any advantage to candidates based on submitted rank, so the best approach is just to list the schools you like, in the order you like them.

Beliefs about school admissions chances are off by an average of 30-40 percentage points

Submitting an optimal application under Boston requires families to make complex calculations weighing tradeoffs between how much they like schools and their chances of getting in. This raises the possibility of costly application mistakes. A possible upside is the ability to express the intensity of one’s preference for a particular school by ranking it highly even though one’s chances of admission are low. Whether DA or Boston is the preferable approach depends on the balance between costly application mistakes and the ability to express preference intensity.

In Kapor, Neilson, and Zimmerman (2020), we surveyed households participating in school choice in New Haven, Connecticut about their experiences with and beliefs about the process. We then combined the survey with administrative data from the choice process to identify application mistakes. At the time of the survey, New Haven used the Boston mechanism to assign students to schools.

Our survey results show that families participating in school choice under the Boston mechanism engage in strategic behavior, but often on the basis of inaccurate information. Respondents are more likely to list their stated most-preferred schools first on their choice applications if they think their chances of admission are high. This in principle may be wise strategic behavior. The problem is that beliefs about admissions chances are off by an average of 30-40 percentage points. When we look at the relationship between true admissions chances and the rate at which applicants list their most-preferred school first, we see no systematic relationship. In short, participants engage in strategic behavior, but this behavior appears to be ill-informed in many cases.

How important are belief errors in practice, and does it matter for policy? To get at this question, we formulate a model of school choice in which families choose both whether to participate in school choice and, if they do participate, what ranked list of schools to submit. Families know which schools they like, but have subjective and possibly inaccurate beliefs about their chances of admission at different schools. We use data from the survey and from administrative records of the choice process to estimate the parameters of our model. These parameters capture information about which schools families like and how far off their beliefs about their admissions chances are.

Accounting for the mistakes families make, school choice mechanisms that are simpler for parents seem more appealing from the perspective of student welfare

We use the estimated model to conduct two different kinds of thought experiments. The first asks how aggregate welfare—the sum of the utilities individuals get from the school assignments they receive—would change if New Haven used a different assignment mechanism. We show that, given the belief errors we see, the easier-to-use DA mechanism outperforms the potentially more expressive Boston mechanism. We also find that this conclusion would be reversed if a policymaker could somehow eliminate belief errors, and Boston would then maximize aggregate welfare.

The second kind of thought experiment we consider is what conclusion a researcher seeking to evaluate the welfare tradeoff between DA and Boston would draw if he did not have access to data on belief errors and instead simply assumed that applicants had accurate beliefs. This “rational expectations” assumption is common practice in analyses of school choice when researchers lack data on beliefs (Agarwal and Somaini, 2018; Calsamiglia, Fu, and Guell 2020). However, we show that making it reverses the welfare comparison across mechanisms, making Boston appear preferable to DA. This makes sense, because assuming beliefs are accurate eliminates the central downside of the Boston approach, which is that it is harder for imperfectly informed parents to use. The key takeaway from Kapor et al. (2020) is that families make mistakes when participating in school choice and that, once one measures and accounts for these mistakes, approaches to school choice mechanism design that make things simpler for parents seem more appealing from the perspective of student welfare. This is in addition to other benefits that previous authors have attributed to strategically simple approaches, such as transparency (Abdulkadiroglu, Pathak, Roth, and Sonmez 2006). Findings from our paper led New Haven to change its assignment mechanism from Boston to DA in 2019 (Akbarpour et al. 2022).

Smart matching platforms and belief errors in strategyproof school choice

Are policymakers and market designers done at this point? Does switching to a strategyproof mechanism solve the problems that inaccurate beliefs generate for school choice participants? In canonical formulations of the school choice problem, invoked in Kapor et al. (2020) and many other analyses of school choice, the answer is yes. In a strategyproof mechanism, you do not need to have accurate beliefs to submit your best application; you just need to know your own preferences. But the idea that applicants know their own preferences is a strong assumption in its own right. When there are many schools to choose from, applicants may not know all of the schools available to them, or how much they like those schools.

Arteaga et al. (2022) picks up the thread here. We ask whether school choice participants know about the schools available to them, how choice outcomes are shaped by the interaction of inaccurate beliefs with the challenge of learning about schools, and what policymakers can do about it.

We start by providing survey evidence that searching for schools is costly and that search costs place beliefs about assignment chances back in a key role even when the assignment mechanism is strategyproof. We surveyed roughly 50,000 families who participated in the Chilean school choice process, which assigns students to schools using the DA mechanism. We find that families have limited knowledge of nearby schooling options. For example, only 17% report that they know a lot about a randomly chosen school within 2 kilometers of their home.

The idea that applicants know their own preferences is a strong assumption

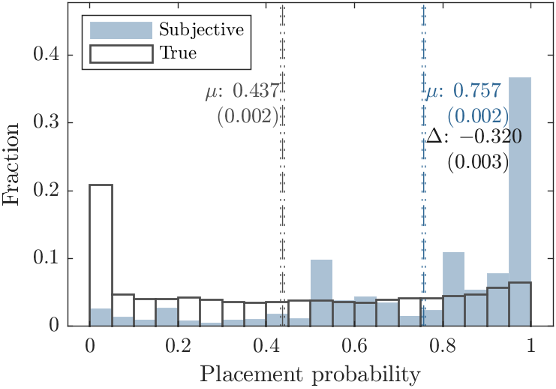

Limited knowledge of nearby schools is tightly connected to beliefs about admissions chances. When asked why they stopped adding schools to their application, the most common reason respondents gave was that they thought they would receive a placement at a school already on their list. Roughly half of respondents who reported being sure they would be admitted to some school on their list gave this reason, compared to less than 10% of respondents who thought they were unlikely to be admitted. The connection between beliefs and search leads to bad outcomes, because some respondents have wildly inaccurate beliefs about their admissions chances and do not search enough. In this setting, applicants facing non-placement risk overestimate their admissions chances by about 30 percentage points on average. The mean subjective admissions belief for applicants with true chances near zero is about 70%. Figure 1 displays histograms of actual and subjective admissions beliefs for applicants whose chances of non-placement are greater than zero. People who stop search because they incorrectly think they are going to be placed are at risk of not receiving any placement. In this case, most resort to a scramble in which students must find and enroll in schools outside of the centralized process.

Figure 1: Histograms of subjective and true non-placement probabilities

Fraction of observations in different placement probability bins. Both subjective survey reports (in blue) and true values (black outline) are displayed. The figure also reports the mean values of the actual and subjective reports (labeled µ) and the difference between them (labeled Δ). Standard errors are in parentheses. Sample: participants in a survey of participants in the 2020 centralized choice process in Chile.

To help policymakers address the problem of inaccurate beliefs and limited search, we worked with NGOs and policymakers to design, evaluate, and deploy at scale a new kind of information intervention, called a smart matching platform (SMP). SMPs aggregate data on the distribution of applications from the back end of the choice platform and use it to provide live feedback to applicants interacting with the front end—i.e., the choice application.

In this case, we designed a treatment that warned applicants submitting risky applications that they were at substantial risk of nonplacement. The main form of this intervention was a platform pop-up that appeared as users attempted to submit a risky application. Since 2018, all participants in the Chilean choice system who submitted choice applications where predicted nonplacement risk was 30% or higher have received a warning of this type.

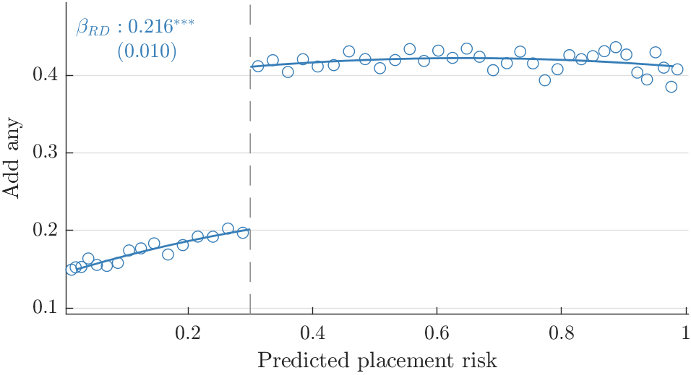

The 30% risk cutoff lends itself naturally to evaluation via regression discontinuity design. As shown in Figure 2, crossing the risky cutoff and receiving a warning causes about 22% of applicants to add at least one school to their application. This is among the largest take-up effects ever recorded in the context of a light-touch policy intervention (DellaVigna & Linos 2022). For applicants who add schools to their lists, nonplacement risk falls by 58% and test score value added at the schools they attend rises by 0.10 standard deviations. Most of the gains we observe come from additional placements in undersubscribed schools with excess capacity, suggesting that the gains in match quality result from reducing congestion in the centralized system, not simply shifting who attends a fixed set of desirable, oversubscribed schools.

Figure 2: The effects of receiving a pop-up warning on adding schools to the choice application

The chances that students add at least one school to their application rise by 21.6% when they cross the 30% risk threshold and receive a pop-up warning on the choice platform. Sample: applicants in the Chilean centralized choice system, 2018-2020.

Changes in beliefs seem to be the major mechanism driving the effects of the smart platform intervention. Beliefs about one’s own placement chances fall when students cross the 30% risk cutoff and receive warnings. Alternate interventions that prompt applicants to add more schools to their application but do not provide additional information about risk have limited effects. Personalized warnings about one’s own risk shifts application response more than information about aggregate risks.

Around 22% of school applicants who are warned of their risk of nonplacement add at least one school to their application

In addition to our work in Chile, we implemented and evaluated a smart platform intervention at scale in New Haven, Connecticut. This intervention rolled out in 2020. Our findings in New Haven are similar to those in Chile, though the sample sizes are smaller.

Personal agency, but limited information

A key theme emerging from both Kapor et al. (2020) and Arteaga et al. (2022) is that school choice participants are sophisticated strategic actors trying to make the best choices they can, but with limited information about both the schools they are choosing from and the process itself.

We identify two approaches for mitigating these information frictions:

- Using strategyproof assignment mechanisms that reduce or eliminate the need for informed strategic play inside the centralized system; and

- Building choice supports such as smart matching platforms that help with the strategic decisions that inevitably remain outside it, such school search.

Beyond the specific results, an important feature of this research is that it has produced sustained and scaled policy change. New Haven and Chile continue to employ the mechanism design and choice support policies discussed here, and, at the time of writing, policymakers in Peru, Ecuador, Colombia, and Brazil either have or are in the process of adopting similar approaches. The close collaboration between researchers, policymakers, and implementation partners that made this work possible may be a useful approach for conducting scalable interventions in other domains.

This article summarizes two articles: ‘Heterogeneous Beliefs and School Choice Mechanisms’ by Adam Kapor, Chris Neilson, and Seth Zimmerman, published in American Economic Review in 2020; and ‘Smart matching platforms and heterogeneous beliefs in centralized school choice’ by Felipe Arteaga, Adam Kapor, Chris Neilson, and Seth Zimmerman, published in The Quarterly Journal of Economics in 2022.

Felipe Arteaga is at the University of California, Berkeley. Adam Kapor is at Princeton University and the NBER. Chris Neilson is at Yale University and the NBER. Seth Zimmerman is at Yale University and the NBER.

Disclosures

Christopher Neilson is the founder and interim CEO of ConsiliumBots, the NGO that implemented the warnings policies described in this brief. Adam Kapor and Seth Zimmerman are academic advisors at ConsiliumBots. Neither Neilson, Kapor, nor Zimmerman received financial compensation from ConsiliumBots or any other source related to this paper. Felipe Arteaga is a research affiliate at ConsiliumBots, and also worked on the team implementing the warnings policy at the Chilean Ministry of Education between 2015 and 2018.