Summary

Many national governments currently face a difficult combination of ageing populations, increasing demands for public spending, slow growth, and high public sector debt. Some commentators advocate taxing the wealth of the rich, but such proposals continue to divide economists. The authors of a new study examine the case of Colombia, which has one of the most ambitious and long-standing wealth tax regimes in the world. This experience can be used to learn how Colombian taxpayers, especially those at the very top of the wealth distribution, responded to wealth tax reforms over two decades. The new study has important lessons for policymakers considering the use of wealth taxes, and indicates how such taxes could be made more effective in raising revenue.

A first result from the new study is that taxpayers respond quickly to changes in tax rates. For example, Colombia expanded its wealth tax in 2010, which led to ‘bunching’ just below the new exemption thresholds; this suggests that some individuals were misreporting their assets. Overall, up to 20% of the expected revenue from new wealth taxes was lost due to immediate behavioral responses. The effects can persist over time: Even after a specific wealth tax was repealed, many taxpayers continued reporting lower wealth levels for years, perhaps in the belief that wealth taxes might be increased in future.

To understand how wealth can be misreported, the researchers use Colombian tax data to separate assets into those with and without third-party reporting, where the latter asset holdings will be much harder for the authorities to verify. Those taxpayers who ‘bunch’ below thresholds seem to disproportionately reduce reported holdings of unverifiable assets, while inflating liabilities. The researchers also link tax data to information from the Panama Papers leak in 2016, and show that the wealthiest Colombians increased their use of offshore entities in response to higher tax rates.

The new study has a number of lessons for governments considering wealth taxes. Enforcement design matters; behavioral responses are real, but could be overcome by measures such as improved audits or disclosure programs; temporary taxes can have lasting effects; and the global nature of evasion means that countries should cooperate in exchanging financial account information. With better enforcement, smarter design, and global cooperation, governments may yet find a way to tax wealth without seeing some of it vanish.

Main article

As governments around the world grapple with inequality and fiscal recovery after the Covid-19 pandemic, the idea of taxing the wealth of the rich has regained political momentum. Economists, however, remain divided. Some argue that wealth taxes are a powerful tool to curb rising inequality and fund public services, while others warn of evasion, capital flight, and limited revenue potential (for discussions, see Advani et al. 2021 and Scheuer and Slemrod 2021).

Yet because few countries levy wealth taxes, relatively little is known about the actual responses of wealthy individuals when governments tax their assets – especially in countries outside Europe. The research summarized here provides new evidence for Colombia, a middle-income country with one of the most ambitious and long-standing wealth tax regimes in the world. Its policy changes over time can be used to understand how tax rates affect reported asset levels.

In more detail, the new study examines how Colombian taxpayers, especially those at the very top of the wealth distribution, responded to wealth tax reforms over two decades. Using administrative tax returns from 1993 to 2016, linked to data from the Panama Papers leak in 2016, we show that people respond quickly and persistently to wealth taxes. They report less wealth immediately after reforms, and many continue doing so years later, even after the tax has been repealed. They also exploit enforcement gaps by misreporting hard-to-verify assets and shifting wealth to offshore tax havens.

Yet because few countries levy wealth taxes, relatively little is known about the actual responses of wealthy individuals when governments tax their assets

In short: Wealth taxes can work, but behavioral responses – especially by the richest – are real, strategic, and can persist long after they might have been expected to fade away.

Why tax researchers can learn from Colombia

Colombia offers a rare ‘natural experiment’ in wealth taxation. Between 2002 and 2016, it implemented four major reforms to a national wealth tax on individuals with substantial net worth, typically in the top 0.1% of the distribution. Tax rates reached as high as 6%, and tax schedules featured ‘notches,’ where small differences in reported wealth could lead to large jumps in tax liability.

The country also boasts unusually rich data. Wealth information is collected on personal income tax returns and, crucially, linked to third-party financial records – though coverage is limited for non-financial assets like real estate, business inventories, and personal loans. Enforcement capacity has historically been weak, especially for ultra-wealthy individuals. The proximity of Panama, long a favored tax haven for Colombians, poses a major challenge to effective capital taxation.

Wealth taxes trigger fast responses

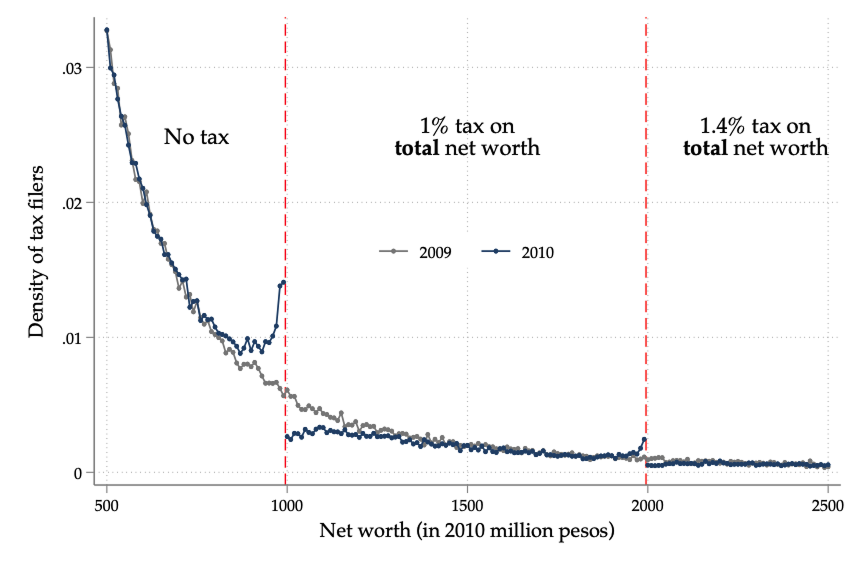

We start with the basics: Do taxpayers respond when a wealth tax increases? Yes – and fast. When Colombia expanded its wealth tax in 2010, ‘bunching’ can be seen just below the new exemption thresholds, as in Figure 1. For example, taxpayers with wealth just under 1 billion pesos (≈USD $500,000) faced no tax, while those just over had to pay 1% of their entire taxable wealth. This created strong incentives to misreport.

Figure 1: Taxpayers immediately bunch to avoid higher wealth taxes

Notes: This figure shows that taxpayers respond to wealth taxation by bunching just below the thresholds where tax liability increases. It plots the distribution of reported wealth before (2009) and after (2010) a reform that imposed a wealth tax on individuals reporting at least 1 billion pesos (USD 520,830). The reform introduced two notches at 1 and 2 billion pesos (red vertical lines), creating discrete jumps in tax liability. While the pre-reform distribution is smooth, the post-reform data exhibit excess mass just below the notches and missing mass just above them – evidence of behavioral responses to the tax. Source: Authors’ calculations using administrative data from DIAN.

Wealth taxes can work, but behavioral responses – especially by the richest – are real, strategic, and can persist long after they might have been expected to fade away.

Using bunching and “difference-in-differences” statistical approaches, we estimate an elasticity (a measure of responsiveness) of reported wealth with respect to the net-of-tax rate of 2. This is larger than estimates for Sweden and Norway, where elasticities are near zero (Ring, forthcoming; Seim, 2017), but smaller than in Switzerland, where the absence of third-party reporting led to substantial evasion across cantons (Brülhart et al. 2022). In Colombia, up to 20% of the expected revenue from new wealth taxes was lost due to immediate behavioral responses.

Wealth taxes leave a lasting mark

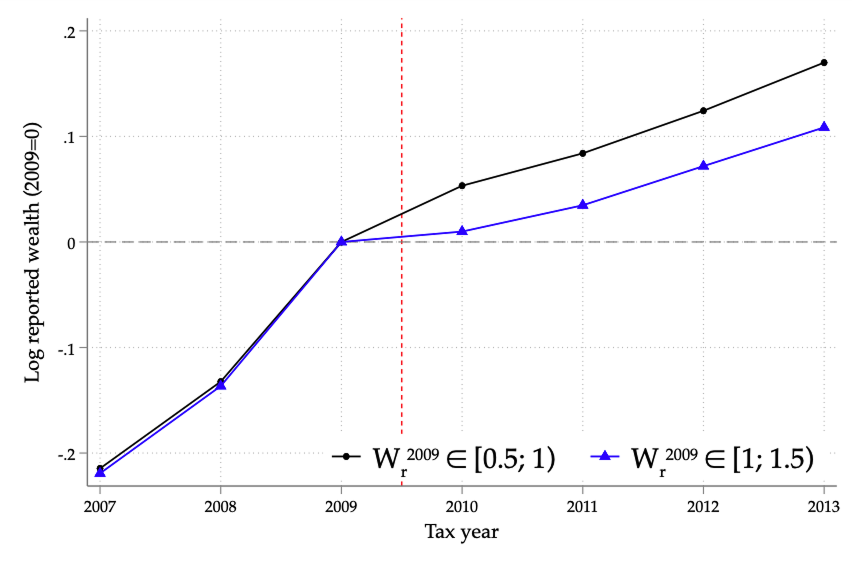

Another finding is more surprising. Even after a specific wealth tax was repealed, many taxpayers continued reporting lower wealth levels for years. This “hysteresis” effect, or behavior that persists even in the absence of current incentives, is rare in tax policy research. We show that taxpayers bunch below nominal exemption thresholds well after the tax ends, and even report slower asset growth over time. This can be seen in Figure 2.

Figure 2: A temporary wealth tax generates persistent effects

Notes: This figure shows that the temporary 2010 wealth tax – targeting individuals reporting at least 1 billion pesos – triggered an immediate response that did not fade away. Remarkably, the effects were still visible four years later. Source: Authors’ calculations using administrative data from DIAN.

Offshoring was not just symbolic… after creating an offshore entity, individuals significantly reduced the asset holdings they reported to Colombian authorities.

Our evidence suggests strategic motives for this. Taxpayers may fear that future governments will reintroduce wealth taxes, and they do not want to raise red flags by reporting higher wealth now. In Colombia, the thresholds defining tax brackets (1 billion, 2 billion, 3 billion pesos) remained fairly constant across reforms, making them salient focal points.

This behavior goes beyond inertia. We find no evidence that costs to adjusting asset levels explain the patterns in the data. Instead, taxpayers appear to be playing a long game: strategically misreporting to avoid detection, much like the forward-looking evasion behavior in France documented by Garbinti et al. (2023).

The rich can hide wealth

Next, we ask: How do the wealthy misreport? The answer depends on what the tax authority can see. Colombian tax data allow us to decompose assets into those with and without third-party reporting. Unsurprisingly, we find that ‘bunchers’ disproportionately reduce reported holdings of unverifiable assets – like private business inventories and interpersonal debts –while inflating liabilities. For instance, some taxpayers report fictitious loans to family or friends who are below the tax threshold, allowing both parties to reduce their tax burden. This tactic was a known feature of evasion during our study period.

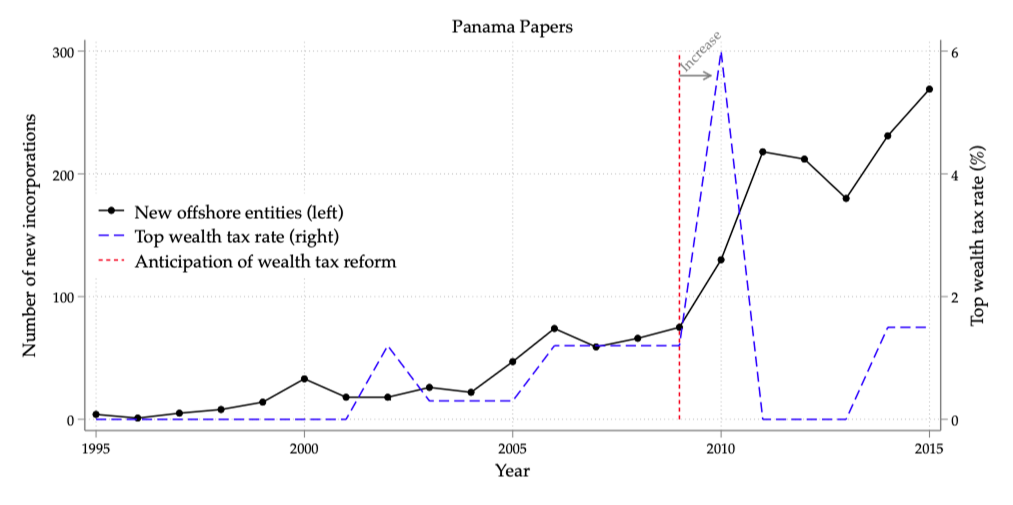

And then there’s offshoring. By linking tax data to the Panama Papers – documents leaked from Mossack Fonseca, a major shell company provider, in 2016 – we found that the wealthiest Colombians increased their use of offshore entities in response to wealth tax hikes, as shown in Figure 3. After the 2010 reform, offshoring spiked, especially among those subject to the tax. Those named in the Panama Papers were 40 times more likely to be in the top 0.01% of the Colombian wealth distribution than in the top 5% overall.

Figure 3: Wealth tax hikes trigger offshoring to tax havens

Note: This figure tracks how often Colombians set up offshore entities in tax havens over time (black line), alongside changes in the top statutory wealth tax rate (blue dashed line). The pattern is clear: when tax rates go up, so does offshore activity. Source: Authors’ calculations using Panama Papers and Offshore Leaks data (ICIJ, accessed June 12, 2017).

Offshoring was not just symbolic. Statistical methods for studying the effects of discrete events reveal that, after creating an offshore entity, individuals significantly reduced the asset holdings they reported to Colombian authorities.

What this implies for tax policy

Our findings have important lessons for policymakers considering wealth taxes.

First, enforcement design matters. Wealth taxes are more likely to succeed when asset verification is robust. Colombia’s experience shows that individuals adjust what they report, especially when asset categories are not independently verifiable. Increasing third-party reporting and data-sharing across agencies can narrow these gaps.

Colombia’s experience shows that individuals adjust what they report, especially when asset categories are not independently verifiable.

Second, behavioral responses are real, but can be overcome. Strategic misreporting drives much of the behavioral response to the wealth tax in Colombia. This means governments may recover revenue through improved audits or disclosure programs, as shown by subsequent reforms (Londoño-Vélez and Ávila-Mahecha 2021).

Third, temporary taxes can have lasting effects. Even short-lived wealth taxes leave a behavioral imprint. If future taxes are anticipated or feared, people will act accordingly. This brings both risks and opportunities. Governments should consider how announcements and policy stability influence compliance.

Fourth, the global nature of evasion means that countries should coordinate. Tax havens weaken national tax bases. Our study reinforces the need for international cooperation through automatic exchanges of financial account information and the OECD’s Common Reporting Standard. Without these measures, wealth taxation – even when well-designed – is likely to prove leaky at the top.

In summary, Colombia’s wealth tax experience shows both promise and peril. When implemented, the tax raised revenue from the richest. But it also triggered immediate and strategic avoidance, with behavioral effects that persisted long after repeal. With better enforcement, smarter design, and global cooperation, governments may yet find a way to tax wealth without seeing some of it vanish.

This article summarizes “Behavioral Responses to Wealth Taxation: Evidence from Colombia” by Juliana Londoño-Vélez and Javier Ávila-Mahecha, forthcoming in the Review of Economic Studies.

Juliana Londoño-Vélez is an Assistant Professor of Economics at the University of California, Los Angeles. Javier Ávila-Mahecha is an official in tax administration at DIAN, the Directory of Taxes and Customs of Colombia.

References and further reading

Advani, A., Miller, H. and Summers, A. (2021). “Taxes on Wealth: Time for Another Look?” Fiscal Studies, 42, 389-395.

Brülhart, M., Gruber, J., Krapf, M. and Schmidheiny, K. (2022). “Behavioral Responses to Wealth Taxes: Evidence from Switzerland”, American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 14(4), 111-50.

Garbinti, B., Goupille-Lebret, J., Muñoz, M., Stantcheva, S. and Zucman, G. (2023). “Tax Design, Information, and Elasticities: Evidence from the French Wealth Tax”, NBER Working Paper no. 31333.

Jakobsen, K., Jakobsen, K., Kleven, H. J., and Zucman, G. (2020). “Wealth Taxation and Wealth Accumulation: Theory and Evidence from Denmark”, Quarterly Journal of Economics, 135(1), 329-388.

Londoño-Vélez, J. and Ávila-Mahecha, J. (2021). “Enforcing Wealth Taxes in the Developing World: Quasi-Experimental Evidence from Colombia”, American Economic Review: Insights, 3(2), 131-48.

Ring, M. (forthcoming). “Wealth Taxation and Household Saving: Evidence from Assessment Discontinuities in Norway”, forthcoming in the Review of Economic Studies.

Scheuer, F. and Slemrod, J. (2021). “Taxing Our Wealth”, Journal of Economic Perspectives, 35(1), 207-230.

Seim, D. (2017). “Behavioral Responses to Wealth Taxes: Evidence from Sweden”, American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 9(4), 395-421.