Summary

The desirability of wealth taxation depends on the extent to which it distorts savings decisions. However, economic theory is ambiguous whether wealth taxation causes households to save more or less due to two opposing forces. Wealth taxes make future consumption relatively more expensive, thereby potentially increasing current consumption—this is known as the (intertemporal) substitution effect. The income effect works in the other direction; by reducing future after-tax incomes, households are forced to increase their saving to maintain their planned future consumption. The net effect of these two forces on saving is ambiguous and will depend on how willing households are to adjust their consumption over time.

This article uses quasi-experimental variation in the Norwegian wealth tax to study how wealth taxation affects households saving and labor supply behavior. Reforms that allow researchers to causally identify the effects of wealth taxes are hard to come by, but a 2010 Norwegian reform differentially affected households based on their residential address. A new model was used to assess the value of individual’s houses for the purpose of assessing their wealth. This model was saturated with geographic fixed effects, causing large discontinuities in estimated housing wealth—and therefore in whether and how much wealth tax individuals would pay in wealth taxes—across geographic boundaries. Importantly, the reform affected marginal tax rates on all assets. This paper also uses predominantly third-party reported measures of financial wealth, which limits measurement issues related to tax avoidance and evasion.

The results of this study indicate that higher exposure to wealth taxation causes households to save more as opposed to less. The rate at which households save increases, mostly by increasing liquid financial wealth. The effect is relatively large: for each additional NOK of wealth tax, households increase their net financial saving by 3.76 NOK, which is enough to finance future wealth taxes. There is no evidence of bunching around the tax threshold in Norway—a phenomenon that has been observed in other countries—suggesting that wealth tax enforcement that relies on third-party reporting is successful in limiting evasion. This increase in saving is primarily financed by increased labor earnings, which are driven by extensive-margin labor supply responses.

These findings differ from those of studies from other countries, which have found substantial negative elasticities of taxable wealth with respect to the wealth tax rate. This difference may be due to the time periods being studied or the present study’s focus on third-party-reported measures of savings.

Perhaps the key lesson for policymakers is that distortions to saving behavior should not be the main concern when considering whether to tax capital more aggressively. Instead, these findings—when set within the context of the existing literature—suggest that limiting avoidance and evasion should be the main concern. These results, while not a comprehensive evaluation of wealth taxes, may also be informative of responses to other shocks or policies that affect the after-tax return on savings, such as capital income taxation.

Main article

This article uses quasi-experimental variation in the Norwegian wealth tax to study the theoretically ambiguous question of how wealth taxation affects household saving and labor supply behavior. Results indicate that the higher exposure to wealth taxation causes households to save more, suggesting that the income effect of these taxes outweighs the intertemporal substitution effect. These findings differ from those of studies from other countries, which have found substantial negative elasticities of taxable wealth with respect to the wealth tax rate. The findings suggest that limiting tax avoidance and evasion, rather than distortions to saving behavior, should be the main concern of policymakers considering a tax on capital.

The desirability of wealth taxation depends on the extent to which it distorts savings decisions. However, economic theory does not provide firm guidance on the magnitude or even the sign of this effect. In fact, it is theoretically ambiguous whether wealth taxation causes households to save more or less. This ambiguity is due to two opposing forces. By lowering the after-tax return on wealth, wealth taxes change the relative price of consumption over time. Future consumption becomes relatively more expensive, since you would now have to save even more to afford the same amount of future consumption. This relative price effect increases current consumption, through reduced saving. We typically call this the (intertemporal) substitution effect.

Working in the other direction is the income effect. By reducing future after-tax incomes, households are forced to increase their saving to maintain their planned future consumption. Imagine a sixty-year-old worker planning to spend retirement cruising around in an RV. A wealth tax may mean that the savings they have put aside are no longer sufficient to enable them to afford an RV of the quality they desire. Hence, if they are unwilling to downgrade, they must increase their saving.

Quasi-experimental variation in the Norwegian wealth tax is used to study how wealth taxation affects households’ saving and labor supply behavior.

These two opposing forces, the income and substitution effects, render the net effect of a wealth tax on saving ambiguous. It is more likely to be negative when households are more willing to adjust their consumption over time. In standard economic models, this willingness to adjust is governed by households’ Elasticity of Intertemporal Substitution (EIS). This is an economic parameter that few economists agree on.

Overcoming empirical challenges in studying the effects of wealth taxes

In a recent article in The Review of Economic Studies (Ring, 2024), I use quasi-experimental variation in the Norwegian wealth tax to study how wealth taxation affects households saving and labor supply behavior. The data and methodology used in this study enable me to overcome some of the key empirical challenges in studying these effects.

First, policy variation that allows researchers to identify the causal effects of wealth taxation is hard to come by. Only a handful of countries levy a wealth tax, and policy reforms seldom affect similar households differentially. While policy changes, such as raising exemption thresholds, have differential effects across households (i.e., those already below are unaffected), this differential treatment is linked to households’ wealth levels. Hence, we cannot always be sure that the treatment effect we observe is driven by the policy as opposed to differential innate saving behavior across individuals with different wealth levels.

Higher exposure to wealth taxation causes households to save more as opposed to less.

The innovation in my paper is to exploit a reform that differentially affected households based on their residential address. In 2010, the Norwegian Tax Administration implemented a new model to assess the value of someone’s house for the purpose of taxing their wealth. This new model was saturated with geographic fixed effects, causing large discontinuities in estimated housing wealth across geographic boundaries. Importantly, I demonstrate that these discontinuities do not correspond to discontinuities in other pre-determined characteristics. Instead, they produce geographically discontinuous variation in households’ estimated housing wealth that is uncorrelated with other potential determinants of saving. This variation in assessed housing wealth then provides variation in how much households pay in wealth taxes, and crucially, due to the presence of an exemption threshold, whether they pay a wealth tax. This latter point is important. Some households in high-assessment areas saw their wealth inflated by the new model and were therefore pushed above the wealth tax threshold. Any marginal financial saving is now subject to the wealth tax. My econometric framework compares their saving behavior to that of other households, who live nearby, but saw smaller or negative changes to their housing wealth and thus were less likely to pay a wealth tax.

The second empirical challenge is that household savings are subject to measurement error. Most papers in this literature rely on administrative data provided by tax authorities. Hence, if a tax reform causes households to evade or avoid taxes, the data would suggest that savings decreased. However, savings may simply have shifted to harder-to-tax asset classes, or households may be more likely to misreport their wealth. At the same time, there may be no real response in terms of actual changes to savings.

This increase in saving is primarily financed by increased labor earnings, rather than lower consumption.

The key improvement in my paper is to rely on measures of financial wealth that are predominantly third-party reported. Norwegian financial institutions provide annual snapshots of individuals’ deposits, savings, and securities directly to the tax authorities each year. Hence, this misreporting effect (which may be misinterpreted as dissaving) is mostly absent in the data that I use. In addition, I also study labor supply responses. A common way to save more is to work more, for example, by delaying retirement. Hence, studying labor supply responses provides another proxy for saving responses to wealth taxation that are not subject to the same set of measurement issues described above.

Findings

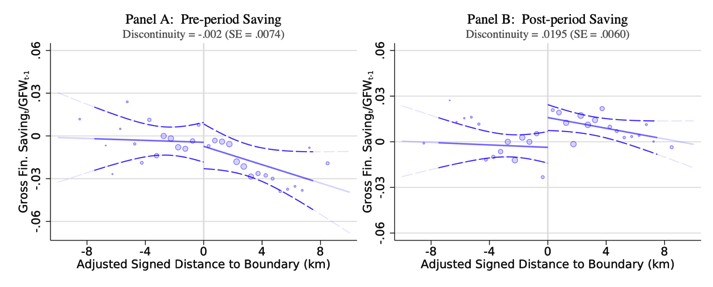

My key finding is that higher exposure to wealth taxation causes households to save more as opposed to less (Figure 1). The rate at which households save increases, mostly by increasing liquid financial wealth. There is no offsetting effect on debt. I find that this increase in saving is primarily financed by increased labor earnings, which are driven by extensive-margin labor supply responses, such as remaining longer in the labor market.

Figure 1: Wealth Tax Exposure and Household Saving

Figure Notes: Households in the same geographic area are sorted according to their distance to the geographic boundary that determines wealth tax exposure, where households on the right-hand-side are more exposed. Households with positive distance values saw higher wealth tax exposure in the post-reform (2010 onward) period. The effect on saving behavior is identified as the discontinuity that occurs at zero. Panel A verifies that there is no effect on saving behavior in the pre-reform period. Panel B considers the post-reform period and finds 1.95 percentage points higher growth rates of gross financial wealth. The corresponding effect for net financial wealth is 3.05 percentage points, which maps into an increase in annual net financial saving of NOK 3.76 per additional annual NOK of wealth tax.

The effect on saving is relatively large. For each additional NOK of wealth tax, households increase their net financial saving by 3.76 NOK, which is enough to finance future wealth taxes. This is reasonable from a lifecycle-theoretic perspective, as the average treated household is close to retirement age and therefore would want to frontload some of the wealth tax burden when they still have significant labor earnings.

There is no evidence of bunching around the tax threshold in Norway, suggesting limited tax evasion.

I also explore the effect on overall taxable wealth, which includes harder-to-assess assets such as other real estate and vehicles. Here, I also find a positive—albeit modest and statistically insignificant—effect. The point estimates are consistent with households responding to wealth taxes by increasing their financial saving without any offsetting reductions in other (perhaps more avoidable) asset classes.

To further investigate whether Norwegians are successful in avoiding wealth taxes, I examine whether there is excess bunching around the wealth tax threshold. If it is easy to misreport wealth to lower your wealth tax, we expect to see many more households located directly to the left of the threshold than to the right. This has been found in other settings, in Sweden, Denmark, Columbia, and Switzerland (Seim, 2017; Jakobsen et al. 2020; Londono-Velez, 2021; Brülhart et al. 2022). However, there is no evidence of bunching around the tax threshold in Norway, suggesting that wealth tax enforcement that relies on third-party reporting is successful in limiting evasion.

To understand how households increase their saving, I also consider the effect on labor supply, as proxied by their labor earnings. I find that households increase their labor earnings by enough to finance almost all the additional saving. Hence, people do not adjust by consuming less. Rather, they work more. A decomposition exercise reveals that this effect is on the extensive margin: households increase the number of days worked, for example by delaying their effective retirement date.

The paper contains additional results as well. I show that wealth taxation does not affect households’ portfolio allocations in terms of what fraction of their financial wealth is allocated to the stock market. I further decompose the implied savings elasticities into elasticities of savings with respect to average and marginal tax rates (ATRs and MTRs). This is possible due to heterogeneity across households of different ex-ante wealth levels in how their wealth tax position was affected. Some households mostly saw higher tax bills, translating into higher average tax rates on wealth. Others were primarily affected on the extensive margin, being pushed from below to above the tax threshold, which changed their marginal tax rate on wealth. Consistent with income effects driving the saving responses, I find large positive effects of increasing ATRs that dominate smaller negative responses to increasing MTRs.

Situating these findings within the broader literature

My overall findings stand in contrast to those in the existing literature. Findings from, for example, Switzerland and Denmark (Brülhart et al, 2022 and Jakobsen et al, 2020) point to substantial negative elasticities of taxable wealth with respect to the wealth tax rate.

My overall findings stand in contrast to those in the existing literature.

A likely explanation for these differences lies in the nature of the underlying data. While my measures of saving are primarily third-party reported, those used in other studies—including, for example, the Swiss setting in Brülhart et al (2022)—rely on purely self-reported measures of wealth. These authors therefore highlight misreporting as a key driver of the sizable elasticities. Differences in the time periods being studied may matter as well. Jakobsen et al (2020) study a wealth tax reform in Denmark in the 1980s, which was a time at which barriers to cross-border evasion strategies were likely considerably smaller.

It is also natural that avoidance and evasion responses (that lower the taxable wealth elasticities) differ across empirical settings in which the wealth tax affects different types of individuals. In Norway, for example, the wealth tax kicks in at about the 85th percentile of wealth. In Denmark, in the 1980s, the wealth tax only applied to the top 2%. These individuals are more likely to own private businesses and are presumably more adept at sophisticated avoidance or evasion (as emphasized by Alstadsæter et al, 2018).

Study limitations

While this research provides a thorough analysis of how wealth taxation affects saving behavior, it is not a comprehensive evaluation of wealth taxes. For example, I do not consider the effect on migration, nor do I consider whether the wealth tax may constrain the investments of business owners through liquidity effects. These potential effects are likely also of significant interest to policymakers who are considering introducing or reforming a wealth tax.

The effects of wealth taxes on charitable giving may also be an important consideration for policymakers, which is something I explore in a recent Review of Economics and Statistics article, Ring and Thoresen (forthcoming). We find that wealth taxation reduces saving, which is inconsistent with the notion that wealth taxes cause accelerated giving as a strategy to avoid taxation.

Distortions to saving behavior should not be the main concern when considering whether to tax capital more aggressively.

Furthermore, while I document no effect of wealth taxation on portfolio allocation, this result comes from a tax reform that did not discriminate between risky (stocks) and safe (deposits) assets. In ongoing work, we show that wealth taxes that include an “equity premium” by imposing lower tax rates on risky assets have material effects on portfolio allocation that materialize over time (Fagereng, Guiso, and Ring, 2023)

Another limitation lies in the sample of households that are studied. My identifying variation primarily comes from moderately wealthy households in the 85th–90th percentiles of the wealth distribution. Hence, my findings primarily speak to the saving responses of these moderately wealthy households as opposed to the potential evasion or avoidance responses of individuals at the very top of the wealth distribution.

Nevertheless, the findings on how saving behavior responds to wealth taxation may be informative of responses to other shocks or policies that affect the after-tax return on savings, such as capital income taxation. In standard optimal tax models, where there is only one asset (such as bank deposits) in which to save, capital income taxes and wealth taxes are equivalent (see, for example, Straub and Werning, 2020). The intuition for why a wealth tax may increase saving applies to capital income taxation as well. If my savings are taxed more heavily, I may need to save even more to afford my planned future consumption bundle, regardless of whether it is a wealth tax or a tax on capital income.

Policy implications

Perhaps the key lesson for policymakers is that distortions to saving behavior should not be the main concern when considering whether to tax capital more aggressively. My findings, set within the context of the existing literature, suggest that limiting avoidance and evasion should be the main concern, along with potential effects on migration.

The potential adverse liquidity effects of a wealth tax on business owners should also be a consideration. In earlier work, I show that adverse wealth shocks to business owners may reduce the growth of their firms, especially in economically turbulent times (Ring, 2023). Since a wealth tax comes due regardless of concurrent profits or cash flows, a wealth tax might have a similar effect on the ability of business owners to grow their businesses. This potential effect of wealth taxation has only received limited attention, with existing studies finding mixed results (Bjørneby et al, 2022; Berzins et al, 2019).

This article summarizes ‘Wealth Taxation and Household Saving: Evidence from Assessment Discontinuities in Norway” by Marius A. K. Ring, published in The Review of Economic Studies in October 2024.

Marius A. K. Ring is at Department of Finance at the University of Texas at Austin and the Department of Economics at Yale University.

References

Berzins, Janis, Øyvind Bøhren, and Bogdan Stacescu. “Shareholder illiquidity and firm behavior: Financial and real effects of the personal wealth tax in private firms.” Centre for Corporate Governance Research, 2019.

Fagereng, Andreas, Luigi Guiso, and Marius Ring. How Much and how Fast Do Investors Respond to Equity Premium Changes?: Evidence from Wealth Taxation. Centre for Economic Policy Research, 2023.

Seim, David. 2017. “Behavioral Responses to Wealth Taxes: Evidence from Sweden.” American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 9 (4): 395–421.

Alstadsæter, Annette, Niels Johannesen, and Gabriel Zucman. 2019. “Tax Evasion and Inequality.” American Economic Review 109 (6): 2073–2103.

Katrine Jakobsen, Kristian Jakobsen, Henrik Kleven, Gabriel Zucman, “Wealth Taxation and Wealth Accumulation: Theory and Evidence From Denmark.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, Volume 135, Issue 1, February 2020, Pages 329–388, https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjz032

Straub, Ludwig, and Iván Werning. 2020. “Positive Long-Run Capital Taxation: Chamley-Judd Revisited.” American Economic Review 110 (1): 86–119.

Brülhart, Marius, Jonathan Gruber, Matthias Krapf, and Kurt Schmidheiny. 2022. “Behavioral Responses to Wealth Taxes: Evidence from Switzerland.” American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 14 (4): 111–50.

Bjørneby, Marie, Simen Markussen, and Knut Røed. “An imperfect wealth tax and employment in closely held firms.” Economica 90.358 (2023): 557-583.

Ring, Marius AK. “Entrepreneurial wealth and employment: Tracing out the effects of a stock market crash.” The Journal of Finance 78.6 (2023): 3343-3386.

Londoño-Vélez, Juliana, and Javier Ávila-Mahecha. 2021. “Enforcing Wealth Taxes in the Developing World: Quasi-experimental Evidence from Colombia.” American Economic Review: Insights 3 (2): 131–48.

Ring, Marius A. K. “Wealth taxation and household saving: Evidence from assessment discontinuities in Norway.” The Review of Economic Studies (2024): rdae100.

Ring, Marius A. K., and Thor O. Thoresen. “Wealth Taxation and Charitable Giving.” Review of Economics and Statistics (2025): 1-45.