Summary

As global competition for high-skilled talent intensifies, policymakers need to understand how inventor migration shapes innovation. New research shows that, while high-skilled migration can lead to brain drain, it can also foster international knowledge transfers that boost productivity in both origin and destination countries. Policy measures should not only seek to attract or retain talent, but also consider how to promote and sustain cross-border collaboration and knowledge diffusion.

To understand what happens when inventors migrate, the important “migration corridor” between the United States and the European Union is a natural place to start. Migration flows between the EU and US are highly asymmetric: EU immigrants to the US contribute significantly to international patents filed in the US, while the reverse flows play a much smaller role for international patents filed in the EU. But the analysis also shows that inventors become more productive after crossing borders. On average, migrants increase their annual patenting by a third after relocating.

Migration also reshapes collaboration networks. Compared to local inventors, migrants develop more diverse networks spanning their origin and destination countries, partly because they continue to work with those back home. And those inventors who remain at home can benefit when a close collaborator migrates; on average, they increase their patent output by 16% in the five years following a co-inventor’s emigration. Hence, migration builds bridges across countries which help to offset the negative effects of brain drain. A new study incorporating these effects also shows that restricting migration entirely would harm both sending and receiving countries.

The same framework can be used to quantify the effects of alternative measures, such as relaxing US immigration caps for high-skilled workers. For the US, this would raise the total number of inventors and expand its innovation capacity. The EU would initially see innovation fall, but then benefit as knowledge and new technologies diffuse from the US. In the long run, the US and EU growth rates would both increase slightly.

The new study also models lower taxes in the EU for foreigners and return migrants, to limit the EU-to-US brain drain. This would increase the number of inventors in the EU, raise innovation, and – in the short term – boost output. But there are also negative effects. A modest tax cut would slightly lower long-run annual growth: losses from reduced learning and diffusion outweigh gains from retaining talent. According to the simulations, managing high-skilled migration is about more than retaining or attracting talent within national borders. It also shapes the broader global innovation ecosystem. The most effective migration policies will take this into account, and preserve the international channels through which ideas and knowledge can spread across borders.

Main article

Debates over high-skilled immigration have become central to economic and political discussion in the US. Some tech leaders and lawmakers push for reforms to streamline visas and offer green cards to STEM graduates and AI researchers, arguing that attracting global talent is vital to maintaining the country’s edge in innovation. At the same time, others voice concern that expanding high-skilled immigration could depress wages or displace US-born workers. Proposals now range from easing visa caps and fast-tracking talent to tightening eligibility and introducing merit-based point systems. But how do such policies shape not just where talent moves, but how knowledge flows, innovation spreads, and productivity converges across borders?

These debates reflect a fundamental tension: high-skilled migration can both enrich and disrupt economies. For origin countries, the loss of talent raises fears of “brain drain,” yet emigrants can also serve as conduits for knowledge transfer back home. For destination countries, migrants boost innovation and expand the talent pool, but may also compete with and displace US-born workers. To quantify the net impact of the positive and negative effects, the research summarized here offers a framework that links individual migration decisions and collaboration patterns with macroeconomic outcomes, and is grounded in both economic theory and data.

The research focuses on a particular group of knowledge workers: inventors, who play a critical role in driving technological progress and innovation. It examines their migration patterns, productivity, and collaboration networks, with a focus on the migration corridor between the United States and the European Union. Using detailed patent data to document empirical patterns, the study then develops a framework that captures the dynamics of talent allocation and knowledge diffusion. The framework can be used to assess the broader economic consequences of high-skilled migration and to evaluate the impact of policy measures, such as tax incentives, visa restrictions, and return migration bonuses, proposed by United States and European Union policymakers to shape and manage the flow of inventive talent.

On average, inventors who remain in the origin country increase their patent output by 16% in the five years following a co-inventor’s emigration.

Tracking inventors across borders

The new study first examines recent migration trends among inventors, focusing on the EU-US corridor – one of the most active flows of high-skilled talent – to uncover how inventor migration shapes innovation dynamics between the EU and the US. In the study, the term EU refers to the European Union member countries prior to Brexit, that is, the current 27 members plus the United Kingdom. Although inventors represent only a small share of the workforce (around 1%-5% in advanced economies), patent data offer a unique opportunity to study international migration by tracking individuals across time and countries. The dataset used in the new study provides detailed information on inventors’ mobility, productivity, and collaboration networks. Migrants are identified by changes in their country of residence recorded in patent filings.

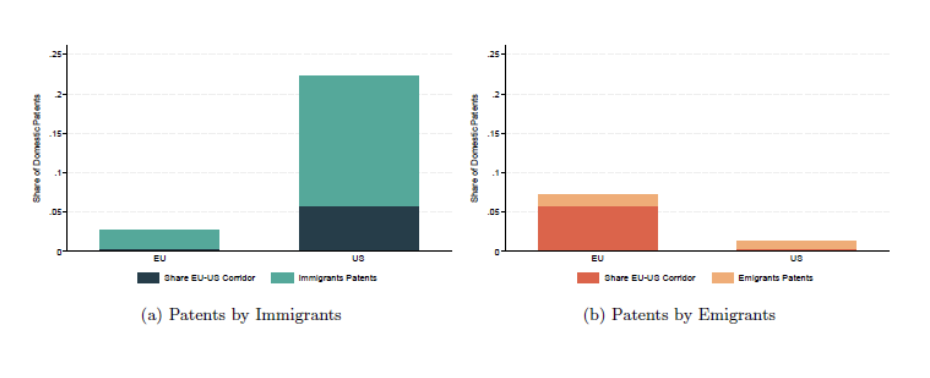

The first key finding is that US-EU migration flows are highly asymmetric. While brain drain is often seen as a problem mainly for developing economies, the EU also faces a significant outflow of inventors to the US. As shown in panel (a) of Figure 1, immigrants account for about 22% of international patents filed in the US under the Patent Cooperation Treaty, with roughly one-third of these coming from EU immigrants. In contrast, only 3% of international patents in the EU are filed by immigrants, with 15% of these originating from US immigrants. Panel (b) shows the reverse pattern for emigration: only 1% of US-born inventors patent abroad, compared to 7% of EU inventors.

Figure 1. Immigration and emigration of inventors in the US and EU, 2000-2010

Notes. Panel (a) illustrates the patents filed by immigrants as a share of patents filed by nationals in the US and EU. Panel (b) illustrates the patents filed by US and EU emigrants in foreign countries as a share of patents filed by US and EU nationals in the home country. The darker shaded areas also highlight the share of patents accounted for by the migrants in the EU-US corridor for each group. Source: PCT Dataset.

Beyond aggregate flows, the study tracks the productivity of individual inventors before and after migration, and this leads to a second key finding. Using a matched “control group” of non-migrating inventors with similar pre-migration characteristics, the analysis shows that inventors become more productive after moving across borders, as illustrated in Figure 2. On average, migrants increase their annual patenting by a third after relocating, with similar patterns observed for both EU and US inventors. Notably, the observed increase in patenting reflects not only the effect of moving, but also how inventors tend to migrate in response to specific opportunities, seeking environments where their skills can be more productively applied, consistent with positive “selection” into migration (those who choose to migrate will often differ in potential outcomes and in other ways from those who do not).

Figure 2. Patenting by migrant inventors around time of migration

Notes. The figure displays changes in migrants’ productivity around migration time relative to the placebo control group. Panel (a) displays the raw means. Panel (b) displays the estimated coefficients for the differences in productivity between migrants and the control group from an event study design.

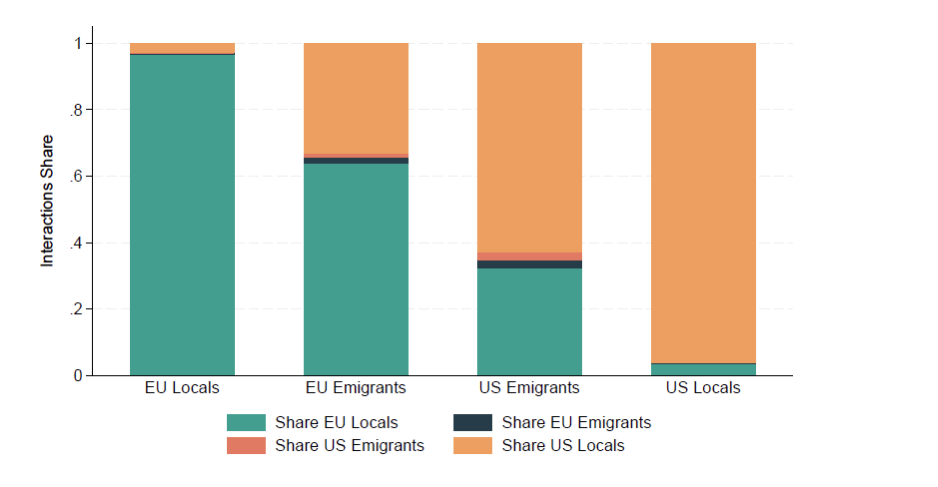

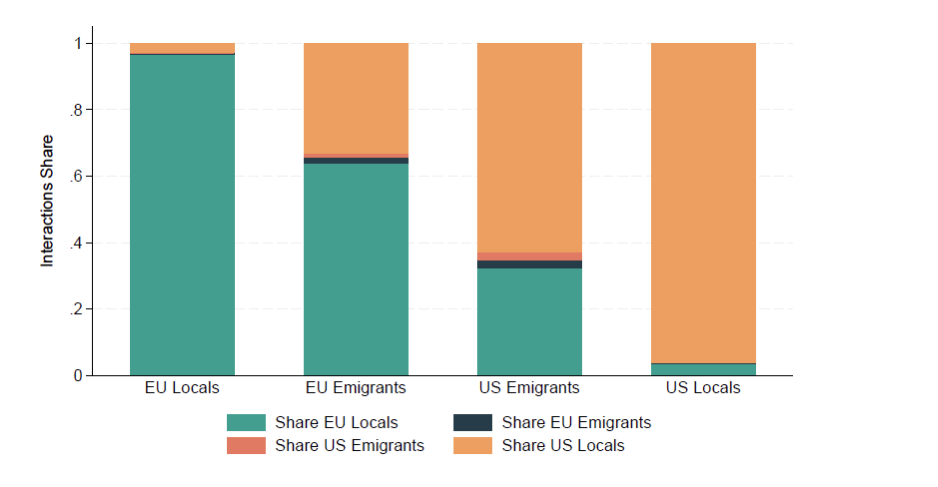

The data also reveal that migration reshapes collaboration networks. While local inventors mainly collaborate with others in the same country, migrants develop more diverse networks spanning their origin and destination countries, as shown in Figure 3. After moving, inventors form more ties in their new location, but maintain ties with colleagues back home. This persistence of cross-border collaboration points to an important mechanism for international knowledge transfer: migration builds bridges across countries, enabling ongoing collaboration and flows of knowledge.

Figure 3. Interaction networks

Notes: Figure based on the inventor-coinventor pairs in the EPO dataset. Inventors are grouped into four categories: EU locals, EU migrants, US migrants, and US locals. For each category, the co-inventors are also grouped into the same four categories. The figure displays the share of co-inventorship relationships belonging to each category.

Even when talent leaves, it can enhance innovation at home through sustained professional ties, a channel often overlooked.

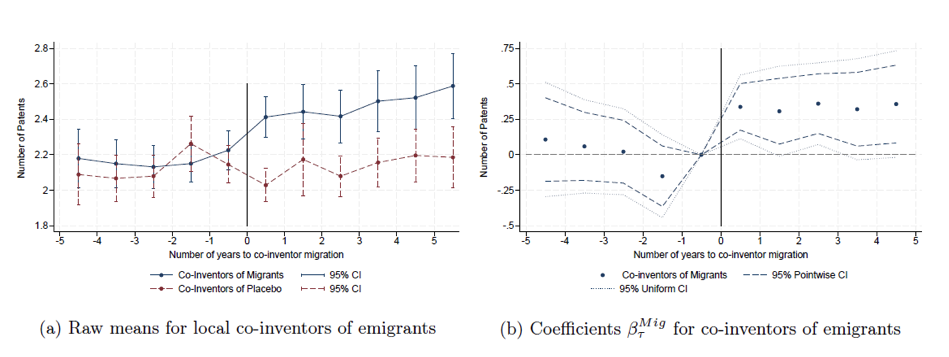

The analysis also finds that local inventors benefit when a close collaborator migrates. On average, inventors who remain in the origin country increase their patent output by 16% in the five years following a co-inventor’s emigration, as shown in Figure 4. The gains are strongest when collaboration continues after the move, suggesting that emigrants serve as “vectors” for knowledge spillovers. Even when talent leaves, it can enhance innovation at home through sustained professional ties, a channel often overlooked in traditional brain drain narratives.

Figure 4. Patenting by co-inventors of migrants around time of migration

Notes. The figure displays the changes in the productivity of local co-inventors of migrants in the country of origin around migration time relative to the co-inventors of the placebo control group. Panel (a) displays the raw means. Panel (b) displays the estimated coefficients for the differences in productivity between the co-inventors of migrants and of the control group from an event study design.

Linking talent mobility to innovation and growth

To understand what these various facts imply, we need a framework that captures the benefits and potential drawbacks of migration for origin and destination countries. The new study introduces such a framework to analyze flows between two locations, here the EU and the US. It shows how high-skilled migration affects innovation and knowledge diffusion, and how inventors make choices about where to live and work based on productivity, learning opportunities, and the value of innovation in different places. These choices shape not only the flow of talent, but also the rate of technological progress.

The model also emphasizes the role of interaction networks. Inventors gain knowledge by learning from others, and the strength and structure of these interactions vary across locations and between locals and immigrants. Migrants can continue collaborating with inventors in their origin location, facilitating cross-border knowledge transfers. These spillovers create cascading effects on innovation and productivity. By capturing both migration and collaboration decisions, the model can predict how migration flows and knowledge diffusion would respond to particular economic conditions and hypothetical policy measures in both origin and destination countries.

The model indicates that cross-border knowledge transfers channeled by migrants help to offset the negative effects of brain drain. Simulations suggest that if EU inventors were to continue to emigrate at current levels but no longer share knowledge with former collaborators, annual EU growth would decline by 10 percent (or 0.12 percentage points) relative to the baseline.

Restricting migration entirely would be harmful to both sending and receiving countries.

Furthermore, restricting migration entirely would be harmful to both sending and receiving countries. In a scenario where EU inventors are no longer allowed to move to the US, long-run growth rates would fall by about 6 percent (or about 0.07 percentage points) in both regions. The restriction is costly because of several effects of migration. First, the US benefits directly from the migration of EU inventors, who expand the talent pool and contribute to US innovation. Second, US inventors gain from collaborating with EU migrants, who tend to be highly productive. Third, although these benefits are partly offset by crowding effects – as immigrants may displace some local inventors – this effect is modest in size. Finally, new technologies developed in the US eventually diffuse to the EU, which benefits indirectly from higher US innovation.

How migration policies shape innovation across borders

Given a detailed model, we can now evaluate other possible policy measures. In both the US and the EU, debates over high-skilled immigration and brain drain have brought migration-related policy measures back to the forefront of economic and political discussion. To address these questions, the model is used to simulate the effects of two hypothetical policies that would aim to influence migration flows, one on the US side and one on the EU side.

In the US example, the model is used to quantify the effects of relaxing immigration caps for high-skilled workers. More precisely, consider a policy to double the annual inflow of foreign inventors, similar in spirit to reforms proposed for the H-1B visa program. This is found to increase the total number of inventors in the US and to expand its overall innovation capacity. While the larger inflow of immigrants slightly crowds out the innovative effort of domestic inventors, this effect is modest, and so total US innovation rises. In the EU, the policy initially lowers innovation, due to talent outflows. This slightly lowers the relative productivity of the EU. But over time, the EU starts to benefit from enhanced knowledge spillovers and technology diffusion from the US. In the long run, both regions experience a 4% increase, or about 0.05 percentage points, in the annual growth rate.

Now consider a hypothetical policy for the EU: what would happen after lowering the tax rate for foreigners and return migrants? This falls within the scope of policies to “reverse the brain drain” seen in several EU countries, including Denmark, France, Ireland, Italy, the Netherlands, and Spain, which offer favorable tax incentives for high-skilled individuals who choose to relocate from abroad.

To study the effects of such policies, the model can be used to quantify the effects of a tax cut for foreign and returning inventors, implemented across the entire EU region. This leads to a reallocation of inventors toward the EU, a permanent increase in innovation, and a short-term boost in output. Hence the policy succeeds in attracting more high-talent individuals, enhancing EU innovation capacity. But over time, the long-run effects are also shaped by some negative forces. The policy may distort optimal location choices, drawing inventors away from more productive opportunities in the US, simply to benefit from tax incentives; and reduced US innovation means that fewer new technologies diffuse to the EU, while lower migration flows limit international learning opportunities.

Policies that increase the international flow of inventors, such as loosening US visa caps, can generate shared gains in long-run growth.

The net effect depends on the scale of the tax cut. A modest tax cut that stops the EU-to-US brain drain, but increases the geographic dispersion of inventors, would lower the long-run annual growth rate by about 3 percent, or 0.04 percentage points. This is because the losses from reduced learning and diffusion outweigh the gains from talent retention. In contrast, a much larger tax cut that attracts US inventors to the EU could relocate the global innovation frontier to Europe. This would raise long-run growth slightly, and reverse the roles of leader and follower between the two regions.

There is an overarching message from these simulations: managing high-skilled migration is not simply about retaining or attracting talent within national borders, but also shapes the broader global innovation ecosystem. Policies that increase the international flow of inventors, such as loosening US visa caps, can generate shared gains in long-run growth through stronger innovation in the leading country and cross-border knowledge spillovers, even if they come with short-term trade-offs for sending countries. Conversely, policies aimed at reversing brain drain, like EU tax incentives for returnees, can boost domestic innovation in the short run, but risk diminishing global learning and technology diffusion if they reduce the overall connectivity of talent across borders. The results suggest that effective migration policies enhance talent mobility while preserving the international channels through which knowledge spreads, and should perhaps include mechanisms to share gains between sending and receiving countries.

While this study focuses on patenting inventors, the findings offer broader insights into how high-skilled migration shapes innovation across sectors. Policies should support not only the mobility of talent but also sustained cross-border collaboration. Looking ahead, several avenues for future research emerge. First, since migration policies may have varying effects for different types of workers, further research should explore how policy measures interact with labor market inequality. Second, the assumption that knowledge flows freely across borders may not hold in sectors with security restrictions or that are otherwise sensitive for strategic reasons, which could limit international spillovers. Finally, the relevance of frontier technologies for lower-income countries – those further from the innovation frontier – remains an open question. Understanding how knowledge spillovers operate in these diverse contexts will be essential for designing effective and inclusive migration and innovation policies.

This article summarizes “The Global Race for Talent: Brain Drain, Knowledge Transfer, and Economic Growth” by Marta Prato, published in The Quarterly Journal of Economics in February 2025.

Marta Prato is an Assistant Professor of Economics at Bocconi University.