Summary

The Affordable Care Act covers 15 million uninsured Americans and substantially expands government health spending, but it is also a major expansion of market-based health insurance. In this market-based approach, the forces of choice and competition shape the products available to consumers, which is usually seen as a good thing. However, asymmetric information can lead to problems of adverse selection, which is the tendency of sicker consumers to sort into generous insurance.

Aware of this danger, the ACA and other market-based programs have responded with a host of policies to combat adverse selection. This paper assesses these policies by studying the Massachusetts pre-ACA health insurance exchange. Massachusetts standardized essentially all plan benefits but allowed insurers flexibility to exclude certain providers—including the states’ star hospitals, which are the highest quality and most expensive places to get care. This flexibility can be used as a tool for insurers to “cream skim”, avoiding sicker and higher-cost consumers.

This paper looks at a 2012 natural experiment in which a large plan (Network Health) dropped the star hospitals from its network. This paper lays out three facts about the impact of this strategy shift. First, the plan’s per-enrollee average costs fell by 26%, partly driven by selection changes. Second, Network Health consumers who valued the star hospitals switched out of their plan at rates 4 to 20 times higher than in surrounding years. Third, these consumers switching out of the plan in 2012 had costs more than 108% above those stayers in the plan; the plan benefited financially from them switching out. Given this strong incentive, all but one insurer had dropped the star hospitals from their network by 2014.

Why did Massachusetts’ sophisticated policies fail to neutralize selection incentives? Part of the answer is that risk adjustment can only compensate insurers based on patients’ observed risk predictors, but star hospitals tend to treat patients with high unobserved medical risk. However, unobserved risk is only part of the story. Risk adjustment is based on the idea that consumer costs vary for reasons that can be measured and compensated for. However, costs also vary based on whether a patient uses more or less expensive medical providers when sick. Patients who prefer to use the star hospitals for care incur high costs conditional on medical risk. The paper finds that 12-47% of the adverse selection incentive is explained by this second cost channel.

This finding changes how economists think about the adverse selection problem. In this case, the adverse selection incentives operate to constrain the high costs and market power of star hospitals. While their exclusion makes the insurance product less attractive to consumers, the cost savings are substantially larger by a factor of 3-6x. Overall, if policymakers must choose between full star hospital coverage or exclusion, net welfare is higher under exclusion. That binary choice, however, may be a false one; the real takeaway is that the entire system of allocating access to top hospitals via insurance plan choice is unlikely to work well. Instead, the focus should be on creative policies that allow insurers to offer more targeted access to top-quality but expensive star providers to those patients who most need them.

Main article

The Affordable Care Act represents a major expansion of market-based health insurance. In addition to the advantages stemming from choice and competition, market-based approaches can lead to problems of adverse selection. This paper uses the Massachusetts pre-ACA health insurance exchange to show that adverse selection is indeed a persistent problem—due to imperfect risk measurement and preferences for using expensive providers—and that coverage of ‘star’ hospitals is a prime candidate for adverse selection. However, mandating or heavily subsidizing star hospital coverage may, by substantially increasing costs, do more harm than good. Instead, the focus should be on creative policies that allow insurers to offer more targeted access to star providers.

The Affordable Care Act is one of the most significant health reforms in a generation. In addition to covering 15 million uninsured Americans, substantially expanding government health spending, and setting off a fierce political debate, the ACA is notable for an underappreciated reason: it is a major expansion of market-based health insurance.

Traditionally, health insurance in the U.S. was provided outside of standard markets—either by employers or through government programs like traditional Medicare and Medicaid. Individuals had little choice of health insurance plans, and competition—if it occurred at all—was for the business of the employer. Increasingly, however, both public and private health insurance is being provided in a more market-based approach. The ACA is a prime example: it covered the uninsured by establishing a set of state-based markets—called “insurance exchanges”—where enrollees can receive subsidies and choose among plans offered by competing private insurers. A similar market-based approach is also growing in Medicare (via the Medicare Advantage program), Medicaid (via managed care programs), and in employer-sponsored insurance (via private exchanges).

The Affordable Care Act is a major expansion of market-based health insurance.

The insurance markets approach means that the forces of choice and competition shape the products that emerge and become available to consumers. Choice and competition are usually seen as good, but a long tradition in economics suggests the danger involved because insurance suffers from major market failures due to asymmetric information. The most notable market failure is adverse selection—the tendency of sicker consumers to sort into generous insurance—which classic work shows can break down risk pooling and lead to the “unraveling” of generous insurance products (Akerlof 1970; Rothschild and Stiglitz 1976).

Aware of this danger, the ACA and other market-based programs have responded with a host of policies to combat adverse selection, including subsidies, benefit regulation to ensure minimum quality, and risk adjustment transfers across plans. The hope is that these policies will do enough to correct market failures so that the ACA can leverage the benefits of markets—choice, competition, and flexibility to innovate—while avoiding their pitfalls.

This paper provides new evidence to assess how well these systems are working. To do so, it studies the Massachusetts pre-ACA health insurance exchange, which was created in 2006 under the “Romneycare” health reform that was a key model for the ACA. Massachusetts is a particularly well-suited setting to study these issues, both because of its unique setup and its excellent micro-data on insurance choices and costs. Relative to the ACA, Massachusetts took an even more highly regulated approach, completely standardizing most insurance features (e.g., all cost sharing rules) and implementing both subsidies and risk adjustment to mitigate adverse selection.

Market failure can break down risk pooling and lead to the “unraveling” of generous insurance products.

However, Massachusetts applied less regulation to a key attribute: insurers’ networks of covered hospitals and doctors. Insurers had to meet minimum “network adequacy” standards but otherwise had flexibility to exclude certain providers and even to offer very limited or “narrow network” plans. There is good reason for giving insurers this flexibility. Insurers can use the threat of network exclusion as a tool to bargain for lower prices with hospitals and physician groups (Ho and Lee, 2019). But this flexibility also creates a danger that narrow networks become a tool for insurers to “cream skim”, avoiding sicker and higher-cost consumers. Indeed, there have been substantial concerns with the striking growth of narrow network plans in the ACA exchanges (McKinsey, 2017; Dafny et al., 2017). These plans are notable because they tend to exclude the best-known “star” academic hospitals in each area, which are places known for their high-quality and advanced medical care, especially for the sickest patients.

Do cream skimming incentives play a role in the trend towards narrow networks? If so, why are the many policies intended to combat selection falling short? And how should policymakers respond? This paper provides new evidence to address these questions, drawing on the experience of the Massachusetts health insurance exchange.

The Massachusetts Insurance Exchange and Star Hospital Coverage

The paper studies the pre-ACA subsidized Massachusetts health insurance exchange, a program also known as “CommCare.” This setting is particularly well-suited to studying adverse selection and provider networks for several reasons. First, the exchange standardized essentially all plan benefits other than medical provider networks. This lets the paper study selection across plans that differ in networks but are nearly identical in other ways.

Second, Massachusetts has a clear set of star hospitals: the Boston-area Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) and Brigham Women’s Hospital. Perennially ranked by U.S. News & World Report as the best two hospitals in the state (and among the top 15 nationally), these are also merged into a single system that, at the time, was called Partners Healthcare. In addition to being prestigious, the paper shows that these hospitals are expensive, with high prices and treatment intensity. This fits the star hospital paradigm: they are seen as the highest quality but also the most expensive places to get care.[i]

12-47% of the adverse selection incentive is explained by unobserved patient preferences for using more or less expensive medical providers.

Finally, there is variation in insurer network coverage of the star hospitals, both across plans and within plans over time. The paper focuses on a natural experiment in 2012, in which a large plan (called Network Health) dropped Partners from its network in order to facilitate a shift to a narrow network, low-premium strategy. This network change provides ideal evidence to test for adverse selection. By studying sharp changes in demand for the plan in 2012, it gains insight on the types of consumers who most value star hospital coverage—and will switch plans to keep access to it.

Reduced Form Evidence of Adverse Selection

Using this 2012 natural experiment, the paper shows three reduced form facts about the impacts of narrowing networks by excluding star hospitals:

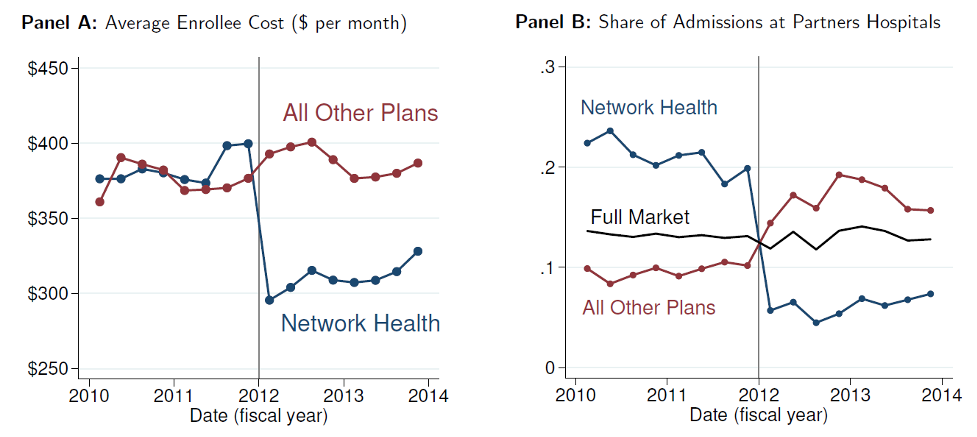

- Dropping the star hospitals led to sharp cost reductions for the excluding plan (Network Health). Its per-enrollee average costs fell sharply (by 26%) at the start of 2012 (Figure 1), and its average costs fell by 21% after risk adjustment. But there were signs these changes were partly driven by selection changes: other plans saw an increase in costs and Partners use in 2012, despite not making any changes to their coverage.

Figure 1: Changes in Costs and Partners Hospital Use around 2012 Network Exclusion

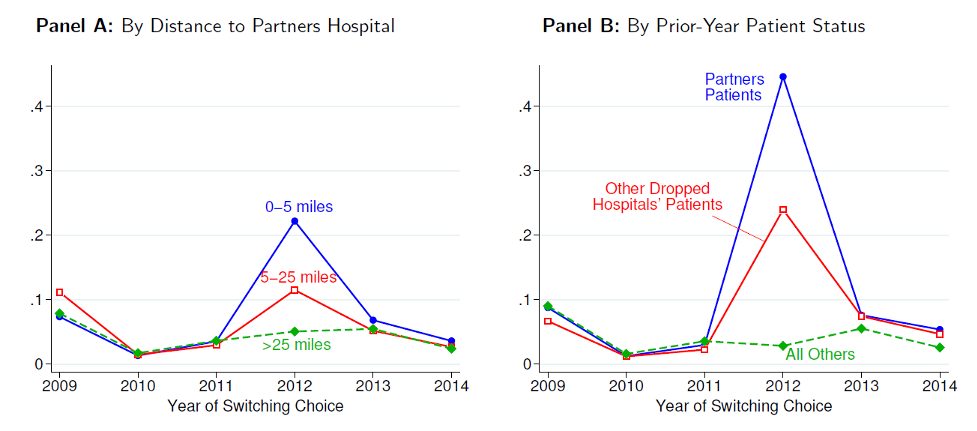

- Consistent with selection, consumers who valued the star hospitals—including people living near Partners hospitals and existing Partners patients—were much more likely to switch out of the plan in 2012, with switching rates 4 to 20 times higher than in surrounding years (Figure 2). These enrollees overwhelmingly switched to the remaining plans that still covered Partners.

Figure 2: Spike in Rate of Switching Out of Network Health after Excluding Partners in 2012

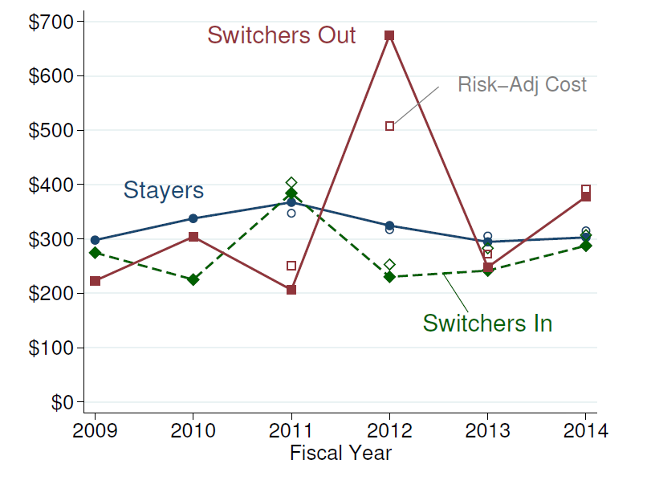

- These consumers switching out of the plan in 2012 had very high costs—with costs more than 108% above stayers in the plan, and 60% after risk adjustment (Figure 3). These high costs meant that this group was highly unprofitable; the plan on net benefited financially from them switching out in 2012.

Figure 3: Adverse Selection – High Cost of Switchers Out of Network Health in 2012

The paper goes on to show that this switching behavior gave the plan a substantial adverse selection incentive to drop the star hospitals. The impact of selection was equal to 78% of the cost savings from exclusion had its enrollment remained constant. Given this strong incentive, other plans soon responded. By 2014, all but one (very high-price) insurer had dropped Partners Healthcare from its network. This near-unraveling of star hospital coverage has persisted into the first years of the state’s ACA exchange.

The incentives of adverse selection operate to constrain the high costs and market power of expensive providers like star hospitals.

Why Did Policies Fall Short? The Role of Preferences and Selection on Moral Hazard

Having shown clear evidence of adverse selection, the paper then asks two key questions. Why did Massachusetts’ sophisticated policies fail to neutralize selection incentives? And how should policymakers respond to rising narrow networks in the ACA and elsewhere?

Part of the answer is that risk adjustment is imperfect: it can only compensate insurers based on patients’ observed risk predictors (including age and medical diagnoses). But star hospitals tend to treat the “sickest of the sick” patients, with high unobserved medical risk. The paper finds that unobserved risk explains about one-third of the higher costs of people who left the Partners-dropping plan in 2012.

However, unobserved risk is only part of the story. The paper argues that there is a second and deeper challenge—one that poses a challenge to the entire risk adjustment approach. Risk adjustment is based on the idea that consumer costs vary because of medical risk, or sickness, which can then be measured and compensated for. But in the networks problem, costs also vary based on whether a patient uses more or less expensive medical providers when sick. The star hospitals are some of the most expensive care providers. Patients who prefer to use them for care—whether healthy or sick—incur high costs conditional on medical risk. And as the evidence shows, a plan that covers the star hospitals attracts precisely those patients with the strongest propensity to use the star hospitals, who therefore have high risk-adjusted costs. The paper finds that 12-47% of the adverse selection incentive is explained by this second cost channel.

Overall, if policymakers must choose between full star hospital coverage or exclusion, net welfare is higher under exclusion.

This channel—selection on propensity to use high-cost hospitals—is a novel one that poses a deep challenge in several ways. First, it undermines standard risk adjustment, which is designed to measure sickness, not hospital preferences. Second, it creates what past work has called “selection on moral hazard” (Einav et al. 2013), which is selection into a plan by people who have the largest cost increases from gaining star hospital coverage (since they are most likely to use its expensive care). Third, it is deeply tied up with the high prices and intensive treatment style of the star hospitals, something that involves real costs that policymakers may not want to subsidize.

This new channel confounds standard policies, but it should also change how economists think about the adverse selection problem. Rather than being a pure problem, the incentives of adverse selection operate as a force that constrains high costs and market power of expensive providers like star hospitals. The paper finds that while their exclusion makes the insurance product less attractive to consumers, the cost savings are substantially larger by a factor of 3-6x. Overall, if policymakers must choose between full star hospital coverage or exclusion, net welfare is higher under exclusion. Policies that mandate or strongly subsidize star hospital coverage may not be warranted.

The real takeaway is that the entire system of allocating access to top hospitals via insurance plan choice is unlikely to work well.

In the end, however, the choice between full star hospital coverage and exclusion may be a false one. The real takeaway is that the entire system of allocating access to top hospitals via insurance plan choice is unlikely to work well. The current system, as the paper shows, leads to unraveling of star hospital coverage, but an alternate system that mandated coverage would lead to undesirably high costs. Instead, the paper suggests considering alternate ways to limit access to expensive star hospitals. These might include higher “tiered” copays at star hospitals, physician incentives to be more cost conscious in referrals, and allowing insurers to cover star hospitals only in specialized cases where their care is most needed.

Take-Aways

Overall, the paper suggests three take-aways for insurance markets like the ACA exchanges:

- Adverse selection is a persistent problem. Despite policies designed to combat it, we should expect that adverse selection persists because of imperfect risk measurement and selection on preferences for using expensive providers.

- Narrow networks are a prime candidate for selection concerns. Coverage of certain hospitals—especially the top star hospitals who offer the most advanced care and treat the “sickest of the sick”—is a prime candidate for adverse selection. If policymakers are concerned about narrow networks, they should look closely at whether this is occurring in their context.

- Creative solutions to the adverse selection problem are needed. The standard response of mandating or heavily subsidizing star hospital coverage may, by substantially increasing costs, do more harm than good. Instead, the focus should be on creative policies that allow insurers to offer more targeted access to top-quality but expensive star providers to those patients who most need them.

The focus should be on creative policies that allow insurers to offer more targeted access to top-quality but expensive star providers.

This article summarizes ‘Hospital Network Competition and Adverse Selection: Evidence from the Massachusetts Health Insurance Exchange’ by Mark Shepard, published in AER in February 2022.

Mark Shepard is at the John F. Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University and NBER.

[i] There is an active debate about whether star hospitals like Partners in fact deliver superior-quality care for all patients, with reasonable evidence on both sides of the issue. This paper does not adjudicate this debate but accepts the widespread perception of high quality, which it confirms in estimates of consumer demand.