Summary

Can increases in the size of the population raise productivity? There are ample theoretical reasons to believe that the answer to this question ought to be yes. Understanding the practical importance of such scale effects is not only of theoretical interest but also extremely policy relevant when thinking about immigration today.

In a recent paper, I exploit a historical natural experiment—the expulsions of ethnic Germans from Eastern Europe in the aftermath of the Second World War—to estimate the size of such scale effects, both in the short and the long run. The expulsions reached a massive scale; by 1950, about 8 million people had been transferred to West Germany. This amounted to an increase of about 20% in the West German population, though the initial allocation of refugees varied dramatically across counties. I use this cross-sectional variation to estimate the relationship between population inflows and subsequent economic development.

Using newly digitized historical data sources for more than 500 counties in West Germany spanning the period from 1933 to the end of the 20th century, I document a sizable positive effect of refugee inflows on long-run local productivity. Counties with a higher share of refugees in 1950 experienced a persistent increase in their population throughout the entire post-war period, and refugee inflows increased local income per capita in the medium and long run (i.e.,the 1960s to 1980s).

I also provide evidence for a plausible mechanism for these results: local industrialization. Refugee inflows are associated with increases in manufacturing employment and declines in agricultural employment, and counties with a higher refugee share experienced an increase in the creation of new manufacturing plants. One reason for the stark expansion of the local manufacturing sector was that the incoming refugees did not have any access to agricultural land, and were therefore the natural “reserve army” for the local manufacturing sector.

These empirical patterns are qualitatively consistent with the narrative of growth models that rely on scale effects: a rising population increases market size for industrial production, which leads to innovative investment (e.g., plant entry). Such investments raise productivity, albeit with a time lag. Moreover, it is precisely such investments that cause the initial shock to be persistent: by raising productivity in the long run, local labor demand and wages increase, which prevents out-migration.

To assess the quantitative implications of this narrative, I construct a novel model of spatial growth and use the results of the natural experiment to estimate its structural parameters. I find that the refugee settlement increased income per capita by about 10 to 15% after 25 years. I also conduct a counterfactual experiment, in which I analyze what would have happened if the military government had been able to implement a more balanced spatial allocation in 1950. The results highlight the tight link between local labor supply and local economic development; the historical “accident” of settling refugees in rural Germany played a key role in the emergence of the German manufacturing base that, even today, is often found in the countryside outside the large cities.

Main article

New work estimates that the settlement of refugees in West Germany after WWII increased income per capita by about 10 to 15% after 25 years. The empirical evidence, made possible by newly digitized historical data sources, indicates that the key mechanism for these productivity gains was local industrialization. These results highlight the tight link between local labor supply and local economic development and are qualitatively consistent with the narrative of growth models that rely on scale effects: a rising population increased market size for industrial production, which led to innovative investments that raised productivity, albeit with a time lag.

Can increases in the size of the population raise productivity? There are ample theoretical reasons to believe that the answer to this question ought to be yes. Most theories of growth predict a positive relationship between innovation incentives and market size, and many models of international trade or development economics highlight the importance of agglomeration forces. Similarly, the empirical regularity that wages are higher in cities is often interpreted as a reflection of mechanisms that rely on a larger population, e.g., knowledge spillovers or labor market pooling.

There are ample theoretic reasons to believe that increases in the size of the population can raise productivity

Understanding the practical importance of such scale effects is not only of theoretical interest but also extremely policy relevant. The potency of such scale effects is, for example, crucial to assess the effects of migration or the consequences of declining population growth—both of which are trends that, if anything, are predicted to grow in importance in the following decades. In my recent paper “Market Size and Spatial Growth – Evidence from Germany’s Post-War Population Expulsions”, published in Econometrica in 2022, I exploit a historical natural experiment to estimate the size of such scale effects, both in the short and the long run.

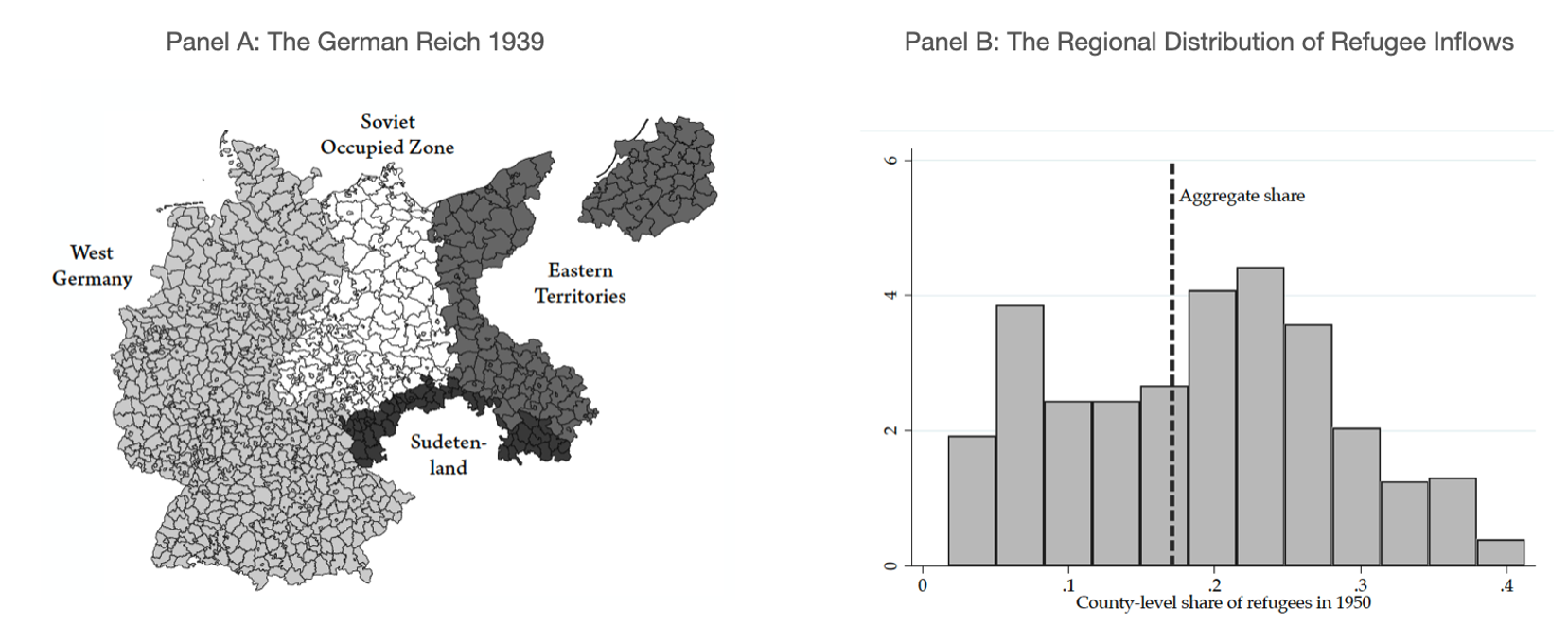

My analysis focuses on a specific historical setting: the expulsions of ethnic Germans from Eastern Europe in the aftermath of the Second World War. Ethnic Germans have been living in Eastern and Central Europe since the Middle Ages. In 1939, on the eve of the Second World War, about 17 million Germans inhabited regions to the east of what is Germany today. The left panel of Figure 1 displays the geography of the German Reich in 1939. The light-shaded areas in the west, labeled West Germany and Soviet Occupied Zone, are the areas that comprise Germany today. In the east, shown in different shades of dark, are the Eastern Territories that encompassed the regions of East Prussia and Silesia, and the Sudetenland, a region located in the north of Czechoslovakia that was annexed by the Nazi Government in 1938. In addition, there were sizable German minorities in Poland, Hungary, and Romania.

Figure 1. The Geography of the Expulsions and the Regional Distribution of Inflows

At the end of the Second World War, the governments of the US, the UK, and the Soviet Union expelled the entire German population from their domiciles in Eastern Europe and transferred them to West Germany and the Soviet Occupied Zone. The expulsions were implemented between 1945 and 1948 and reached a massive scale; by 1950, about 8 million people had been transferred to West Germany. Given the West German population at the time, this amounted to an increase of about 20%.

By 1950, about 8 million people had been transferred to West Germany—a population increase of about 20%

This aggregate increase, however, hides that the initial allocation of refugees varied dramatically across the about 500 counties in West Germany. This large cross-sectional heterogeneity is shown in the right panel of Figure 1, which displays the share of refugees in the county population in 1950. While 40% of the 1950 population were refugees in some counties, others were hardly affected.

In my empirical analysis, I use this cross-sectional variation to estimate the relationship between population inflows and subsequent economic development. Two features of the refugee settlement allow me to address the obvious endogeneity concern that refugees flocked to localities with favorable growth prospects. First, the refugees were not free to settle in the location of their choice; the population transports were organized by the military governments of the US and the UK. Second, the dominant consideration in allocating the inpouring refugees to particular regions was the availability of housing, rather than future economic prospects. For example, P.M. Raup, Acting Chief of the Food and Agricultural Division of the Office of the Military Government of the US, complained as early as 1946 that “both the planning and the execution of the support measures for German expellees was conducted entirely under welfare perspectives. The people in charge at the Military Government are social service officials. … The whole problem has not been handled as one of settlements of entire communities but as an emergency problem supporting the poor.” Hence, the refugee settlement was not conducted with a long-term view on local economic development but rather to address the immediate needs of the refugee population that kept pouring in at the eastern border.

These considerations had specific spatial implications. Because the Allied bombing campaign had reduced the housing stock in many cities by more than 75%, refugees were predominantly assigned to rural localities where housing and food was relatively abundant. These aspects of the post-war policy allow me to isolate the exogenous component of the initial refugee allocation both by flexibly controlling for pre-war measures of economic development and by using an instrumental variable strategy, that exploits the distance to the pre-war population centers in Eastern Europe.

Refugee inflows increased local income per capita in the medium and long run

My analysis relies on a variety of newly digitized historical data sources on population, sectoral employment shares, manufacturing activity, GDP per capita, and the allocation of refugees at the county level, which I spatially harmonized to construct a panel dataset for more than 500 counties in West Germany spanning the period from 1933 to the end of the 20th century. Using these data, I document a sizable positive effect of refugee inflows on long-run local productivity. First, I show that counties with a higher share of refugees in 1950 experienced a persistent increase in their population throughout the entire post-war period. Hence, it was neither the case that refugees left their initially assigned destination counties, nor that their arrival triggered substantial out-migration by natives. Second, refugee inflows increased local income per capita in the medium and long run, once there had been enough time to absorb the new migrants. Whereas income growth between 1939 and 1950 is if anything negatively correlated with refugee inflows, there is a significantly positive relationship between refugee inflows during that period and income growth in the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s.

I also provide evidence for a plausible mechanism for these results: local industrialization. I first show that refugee inflows are associated with increases in manufacturing employment and declines in agricultural employment. Second, I document that counties with a higher refugee share experienced an increase in the creation of new manufacturing plants. Third, for the state of Bavaria, I harmonized data for 6,000 villages and find qualitatively and quantitatively very similar results: refugee inflows persistently increased population density and induced a reallocation from agriculture to manufacturing.

One reason for the stark expansion of the local manufacturing sector was that the incoming refugees themselves often ended up as manufacturing workers. Even though many of them worked in agriculture before the war, agricultural production in the 1940s and 1950s in Germany was still dominated by small farms with little outside employment. And because the refugees did not have any access to agricultural land, they were the natural “reserve army” for the local manufacturing sector.

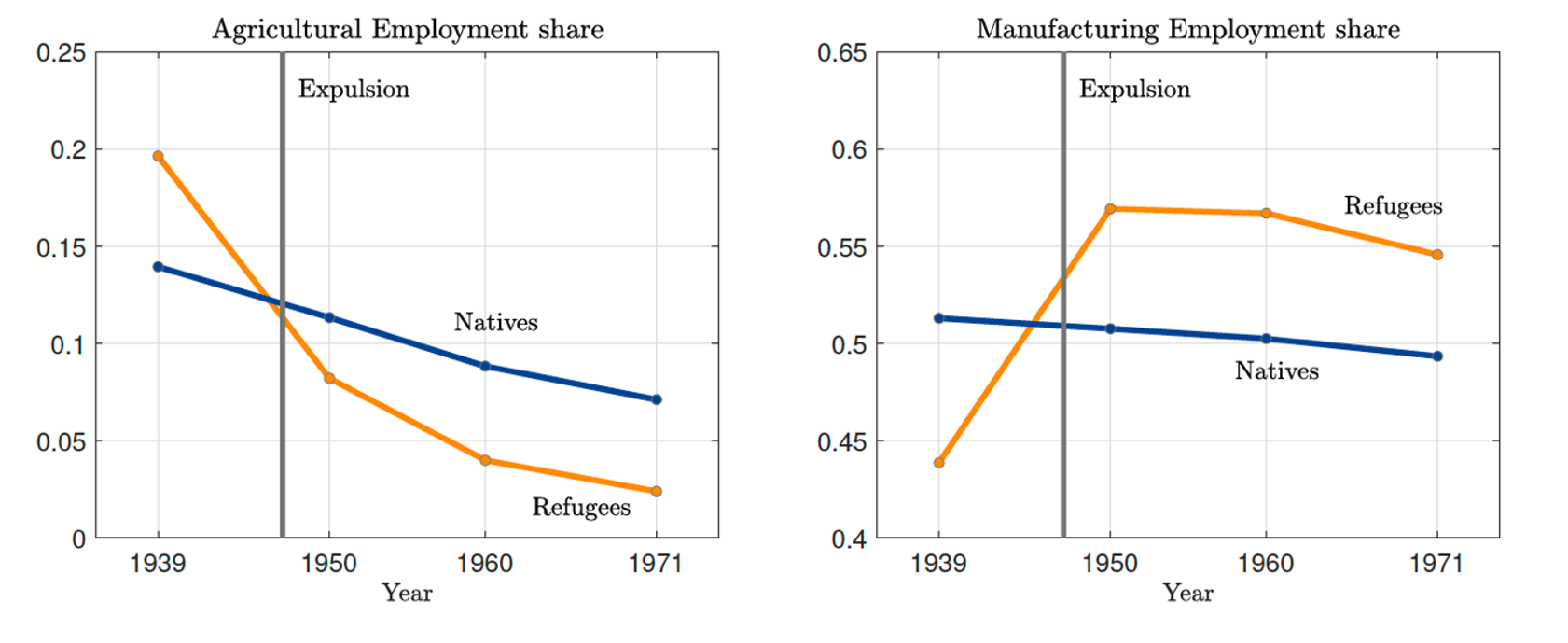

To document this pattern, I exploit a unique supplement to the 1971 population census that asked every respondent where he or she lived in 1939 and in which sector he or she worked in 1939, 1950, 1960, and 1971. By analyzing the responses to these retrospective questions, I can thus measure snapshots of the employment life cycle for both refugees and natives. In Figure 2 I depict this life cycle for the cohort of individuals born between 1915 and 1919. This cohort is 20-25 years old in 1939 and in their late twenties or early thirties at the time of the expulsion around 1947. The differential reallocation of refugees and natives is vividly apparent. Among refugees, 20% of the twenty-year-olds in 1939 used to work in the agricultural sector. After the expulsion, only 8% still did so. In contrast, the share of manufacturing employment within the same cohort increases from 44% to 57% after the settlement. The pattern for natives is strikingly different: shifts in employment shares at the time of the expulsion are hardly noticeable.

Figure 2. The Employment Life-Cycle of the 1915-1919 Cohort

These empirical patterns are qualitatively consistent with the narrative of growth models that rely on scale effects: a rising population increases market size for industrial production, which leads to innovative investment (e.g., plant entry). Such investments raise productivity, albeit with a time lag. Moreover, it is precisely such investments that cause the initial shock to be persistent: by raising productivity in the long run, local labor demand and wages increase, which prevents out-migration.

A plausible mechanism for these results is local industrialization: refugee inflows induced a reallocation from agriculture to manufacturing

To assess the quantitative implications of this narrative, I construct a novel model of spatial growth and use the results of the natural experiment to estimate its structural parameters. In a nutshell, I take the canonical Romer model of economic growth and embed it in a two-sector, multi-region geography model, where goods are traded (subject to trade costs) and people are spatially mobile (subject to migration frictions).

The theory highlights the tight link between local labor supply and local economic development. In particular, the theory shows that even a one-time population increase can have long-lasting effects on local productivity if firms benefit from the existing technology in creating new technologies. This intertemporal spillover is sometimes referred to as firms “building on the shoulders of giants” and is at the heart of any theory of economic growth. Moreover, if population shocks are persistent (as they are in the data), the long-run effect on income per capita can exceed its short-run effect (as it does in the data) if this spillover is sufficiently large. The dynamic evolution of population size and income per capita is therefore governed by the size of spillovers and the costs of migration determining the “stickiness” of the local population.

These empirical patterns are qualitatively consistent with the narrative of growth models that rely on scale effects

I estimate the key parameters of my theory via indirect inference, that is, I replicate the natural experiment of the refugee settlement in my model and target the empirical regression results. I then use the model in two ways. First, I quantify the aggregate effects of the refugee settlement, which, in the presence of general equilibrium effects, are not identified from the cross-sectional empirical analysis (which only estimates relative effects). I find that the refugee settlement increased income per capita by about 10 to 15% after 25 years. Second, I conduct a counterfactual experiment, in which I analyze what would have happened if the military government had not been forced to send refugees to the countryside but had been able to implement a more balanced spatial allocation in 1950. Interestingly, I find that the historical “accident” of settling refugees in rural Germany played a key role in the industrialization of these communities. The rural nature of the historical allocation rule thus acted as a form of “place-based policy” that played an important role in the emergence of the German manufacturing base that, even today, is often found in the countryside outside the large cities.

A natural question is, of course, whether these results can help to predict the consequences of immigration episodes today and to guide policy. While I expect the basic mechanism to apply more generally, at least four aspects of this study seem particularly context specific.

The theory highlights the tight link between local labor supply and local economic development

First and foremost, the German economy had just emerged from the Second World War when the refugee settlement took place. On the one hand, this brought with it specific hardships that might have made the refugees’ integration into the labor market more difficult. On the other hand, new firm creation might have been particularly mobile across space, given the vast degree of wartime destruction. Second, in contrast to other migration episodes, the arriving migrants were ethnically German and shared a common language with the local population. However, the historical literature is full of examples that stress that cultural, religious, and linguistic differences were perceived as being vast back then. It is thus hard to say how the associated challenges to integrate in the German economy compare to the ones faced by, for example, Syrian migrants in Germany today. Third, as highlighted above, the German refugees were allocated to rural areas and not to urban centers. This is in stark contrast to most episodes of voluntary migration both in the modern era and in the past. Finally, the 1950s and 1960s were characterized by a secular rise in the manufacturing sector in Germany. To the extent that agglomeration economies are less potent in services, the productivity effects of immigration might be smaller today.

This article summarizes “Market Size and Spatial Growth – Evidence from Germany’s Post-War Population Expulsions,” by Michael Peters, published in Econometrica in September 2022.

Michael Peters is at Yale University, the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER), and the Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR).