Summary

U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) investments have been responsible for nuclear power, microwave heating, GPS and the Internet. However, in recent decades U.S. defense R&D has lost its luster and fallen away from the frontier of high-tech innovation. In 1976, major American defense contractors produced about 15% more innovations than similar non-defense firms, but by 2019 they appeared between 15% and 40% less innovative.

A new reform at the U.S. Air Force offers compelling evidence that changing how governments procure innovation can dramatically improve outcomes. Specifically, we study the “Open” solicitations, introduced in 2018 as part of the Air Force’s reform of its Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) program, alongside the traditional more narrowly specified “Conventional” solicitations. The Open program allowed firms to propose developing any technology that they thought the Air Force might need, rather than what the government expressly stipulated.

Our research uses rich administrative data between 2003 and 2019 on applications and evaluation scores to assess the impact of winning an award on performance outcomes through early 2023. We identify the causal effects of winning with a sharp regression discontinuity design that compares winning and losing applicants around a cutoff for the award.

Winning an Open award increases the chances of the military adopting the new technology by 11 percentage points and significantly increases dual-use commercialization as measured by subsequent venture capital (VC) investment, which rose by 12 percentage points, and subsequent patenting, which rose by 9 percentage points. Winning a conventional award has no positive effects on any of these outcomes.

We find that the Open program achieved its aim of reaching new types of firms. But could it be that Open program was more successful only due to the type of firms who participated (i.e., selection)? We use three different methods—looking at firm lifecycle measures, machine learning to assess the “openness of topics” as measured by a specificity index, and analyzing effects on firms that applied to both Open and Conventional programs—to test this hypothesis; all three approaches imply that the success of openness not just selection; success is in part due to the way it incentivizes greater innovation from broadly the same pool of firms.

Why does the Open approach—which is already being used across the beyond the DoD—work so well? In part because it provides firms with an avenue to identify technological opportunities about which the government is not yet fully aware but that can represent an entry point to much larger public sector contracts. The dual-use nature of the Open technologies, where firms are encouraged to re-purpose something they are working on for private markets for the defense market, is central to this mechanism.

Our findings have implications beyond defense. Open innovation may be particularly suited to technologies that are more modular, have lower barriers to entry, and benefit from civilian innovation ecosystems. This aligns with the shifting frontier of military technology from highly integrated, capital-intensive platforms toward technologies with strong civilian applications.

Main article

A new reform at the U.S. Air Force offers compelling evidence that changing how governments procure innovation can dramatically improve outcomes. Allowed firms to propose developing any technology that they thought the Air Force might need—rather than asking them to respond to narrow specifications—significantly increased military adoption and dual-use commercialization. The more open program both reached new types of firm and incentivized greater innovation from existing applicants. From a firm’s perspective, government R&D contracts implicitly promise potential future public demand. Open innovation programs may be particularly suited to technologies that are more modular, have lower barriers to entry, and benefit from civilian innovation ecosystems.

Military necessity has been the mother of innovation since antiquity. During the Roman attack on Syracuse in 214 BC, Archimedes invented the “Iron Hand”, a crane to drag enemy ships out of the sea. More recently, U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) investments have been responsible for nuclear power, microwave heating, GPS and the Internet. However, in recent decades U.S. defense R&D has lost its luster and fallen away from the frontier of high-tech innovation.

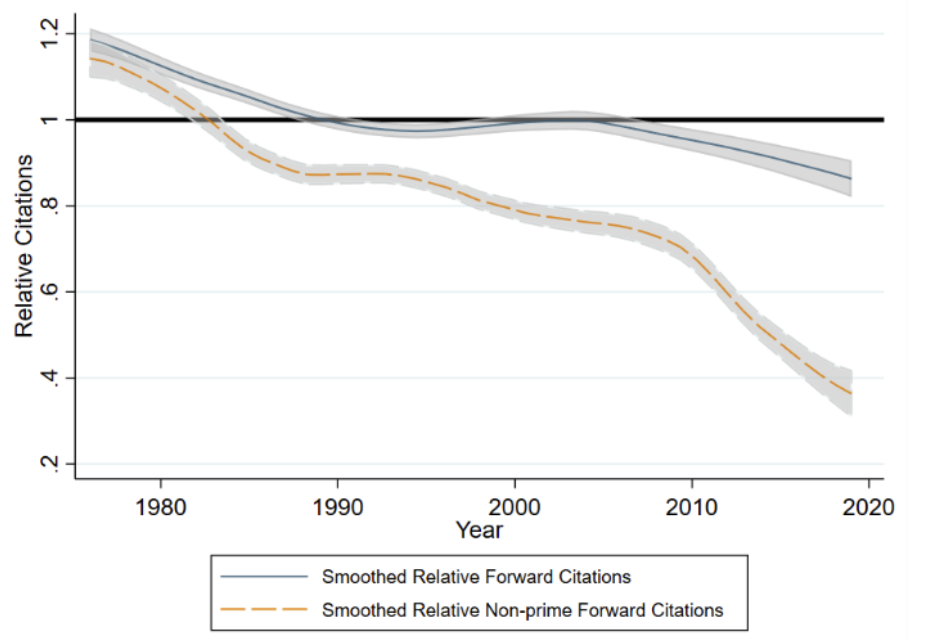

Figure 1: The relative decline in innovation by defense firms 1976-2019

Note: This figure describes patent quality for the six major prime defense contractors in 2019 (Lockheed Martin, Boeing, Raytheon/UTC; Harris/L3; Northrop-Grumman, General Dynamics) and all their acquisitions since 1976. We show the number of patents weighted by the number of future citations in the solid blue line and drop ‘self-citations’ to these primes in the dashed orange line. Both lines are expressed relative to the average in the same technology class-year. The dashed line (i) excludes self-citations and (ii) excludes any citations from prime defense contractors and their acquisitions. The gray band around the relative citations represents the 95% confidence interval.

One measure of this is in Figure 1, where we proxy innovation by the number of patents weighted by future citations. Like academic papers, more citations on average indicate a more impactful piece of work. The lines show the position of the major American defense contractors (‘Primes’) relative to similar non-defense firms. In 1976 these defense Primes produced about 15% more innovations than their peers, but by 2019 they appeared between 15% (if their self-citations were included) and 40% (if we drop self-citations) less innovative. This fall is due to both a relative decline in the number of patents granted to Primes—despite no loss in market share—and the degree to which other firms see their inventions as useful, as reflected in citations. This was a period when there was some overall decline in research productivity (see Bloom et al., 2020), so this shows that defense was doing even worse than the economy as a whole.

Military necessity has been the mother of innovation since antiquity.

Senior U.S. defense policymakers have recognized this problem for at least a decade and see it stemming from both a failure to engage many of the new software-based start-ups and a consolidation among the defense contractors. Traditional defense R&D procurement follows a top-down approach where the military specifies exactly what technology it wants. For example, one Air Force solicitation called for firms to “Develop Capability to Measure the Health of High Impedance Resistive Materials.”

A new reform at the U.S. Air Force offers compelling evidence that changing how governments procure innovation can dramatically improve outcomes. Our paper (Howell et al., 2025) evaluates how the Air Force’s reform of its Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) program has shaped innovation outcomes. Specifically, we study the introduction of “Open” solicitations alongside the traditional more narrowly specified “Conventional” solicitations. The Open program, launched in 2018, allowed firms to propose developing any technology that they thought the Air Force might need, rather than what the government expressly stipulated.

Context: Evaluating the Air Force SBIR Open Reform

By the mid-2010s, U.S. defense innovation faced two interrelated concerns. First, major defense contractors in the sector had consolidated through mergers. Profits had risen substantially yet patenting and innovation quality fell (Figure 1). Second, there was lock-in within SBIR; some firms, pejoratively labelled “SBIR mills”, repeatedly secured awards but rarely transitioned these into usable technologies. The DoD sought to broaden its industrial base by attracting new, entrepreneurial, dual-use firms (firms with both civilian and defense applications). In 2018, the Air Force introduced Open SBIR topics as a reform. These Open topics have quickly scaled across DoD and beyond. There are trade-offs. On the one hand, the open approach may result in too many suggestions that are not useful to the funder. On the other hand, the centralized approach may work poorly if there is uncertainty about what opportunities exist. It could also result in insularity if a small group of firms specializes in the specified projects.

In recent decades U.S. defense R&D has lost its luster and fallen away from the frontier of high-tech innovation.

Our research uses rich administrative data between 2003 and 2019 on applications and evaluation scores to assess the impact of winning an award on performance outcomes through early 2023. We identify the causal effects of winning with a sharp regression discontinuity design (RDD) that compares winning and losing applicants around a cutoff for the award. This enables us to study the causal effects of the two different programs.

The effects of the Open program

We show that winning an Open award increases the chances of the military adopting the new technology by 11 percentage points, 69% higher than the baseline mean (measured by non-SBIR DoD contracts). What is more, winning an Open award significantly increases dual-use commercialization as measured by subsequent venture capital (VC) investment, which rose by 12 percentage points (178% of the mean) and subsequent patenting, which rose by 9 percentage points (79% of the mean). The effects were particularly strong for highly original patents. In stark contrast, winning a conventional award has no positive effects on any of these outcomes. The only effect of such awards was to increase the chances of winning future SBIR contracts – creating exactly the kind of lock-in effect that policymakers wish to avoid.

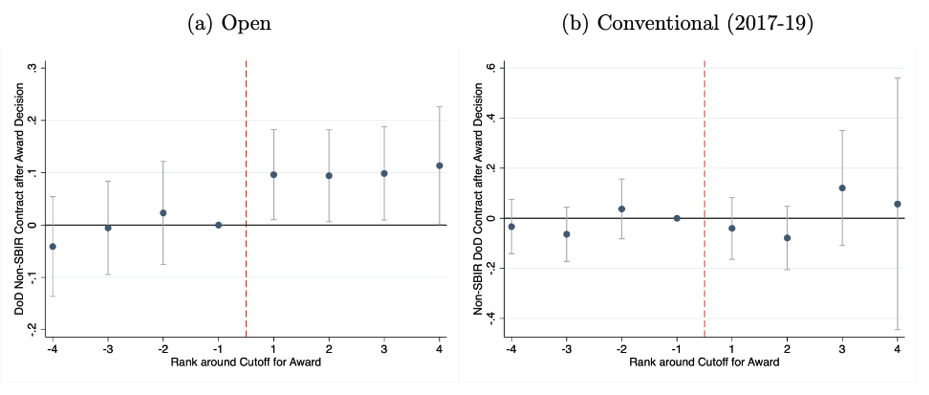

Figure 2: Winning an Open award causes greater technology adoption by the military, but winning a Conventional award does not

Note: These figures visualize the Regression Discontinuity Design (RDD). We use data from applicants for SBIR Awards between 2017 and 2019. We show the probability that an applicant firm obtained a non-SBIR DoD contracts valued at more than $50,000 within 24 months after the award decision (a proxy for technology adoption by the military). In both panels, the horizonal axis shows the rank that evaluators gave to the proposal, focusing on the cutoff for an award. A rank of 1 indicates that the applicant had the lowest scores among winners, while a rank of -1 indicates that the applicant had the highest score among losers. We plot the points and 95% confidence intervals from a regression of the outcome on a full complement of dummy variables representing each rank and fixed effects for the topic. The omitted group is rank = -1.

Why openness matters beyond just attracting different firms

The Open reform sought to broaden the defense industrial base, especially to include new firms. We find that the Open program reached new types of firms like Anduril. Compared to firms applying to Conventional topics, Open topic applicants are younger, less likely to have previous defense contracts, and more likely to be located in high-tech entrepreneurial hubs like Silicon Valley.

Winning an Open award increases the chances of the military adopting the new technology by 11 percentage points.

Although reaching new firms was one aim of the reform, it raises the question of whether the Open program was more successful simply due to the type of firms who participated (i.e., selection). This matters for policy, both within the specific program we study and for considering the implications of our findings in other settings. For example, if certain effects require particular types of firms to select in, the policymaker might consider encouraging those firms to apply without changing the nature of the program. We examine the role of selection using three methods which effectively makes applicants similar to each other and so removes the selection bias.

First, we show that firm lifecycle measures, such as firm age, firm size, and narrow technology class, do not explain the large, positive effects of the Open program versus the null effects of the Conventional program.

The Open program reached new types of firms—younger, less likely to have previous defense contracts, and located in high-tech entrepreneurial hubs.

Second, we used machine learning to classify the degree to which Conventional topics were more or less open as measured by a specificity index. We used an algorithm that represents each proposal as a vector of word embeddings and then measures a topic’s specificity based on the distribution of its applications. If a topic’s proposals are further apart from each other, there is more diversity in the content of proposals, and thus the topic is more “open” and less specific. We found that when conventional topics are more open, they too produce relatively better innovation outcomes.

Third, we examine the effect of the Open program among 507 firms that apply to both Open and Conventional programs, whose unobservable characteristics are tightly matched by construction. Among this set of firms, we still find that large differences in the effects of winning an Open vs. a Conventional topic on performance outcomes.

All three designs balance the characteristics of applicant firms in different ways, but all three imply that the success of openness is in part due to the way it incentivizes greater innovation from broadly the same pool of firms.

Why does the Open approach work so well?

Government R&D contracts implicitly promise potential future public demand. DoD SBIR awards are R&D contracts that offer this implicit potential for subsequent downstream procurement, unlike the R&D grants studied in Howell (2017) and elsewhere. Belenzon and Cioaca (2024) show that R&D contracts crowd-in private R&D investment due to the potential for less competitive downstream procurement. Our evidence indicates that the Open program allows firms to bring new technologies to the defense market that are potentially useful to DoD but, crucially, about which DoD was not previously aware (or was unaware of how they could be useful). This leads them to invest more in innovation, measured both with patents and VC. Startups with a successful Open award can bring evidence to VCs that large defense customers are interested in their commercially driven development efforts, which appears to improve their odds of raising funds.

Government R&D contracts implicitly promise potential future public demand.

In other words, the Open program works in part because it provides firms with an avenue to identify technological opportunities about which the government is not yet fully aware but that can represent an entry point to much larger public sector contracts. The dual-use nature of the Open technologies, where firms are encouraged to re-purpose something they are working on for private markets for the defense market, is central to this mechanism.

An illustrative success story is Anduril, a venture-backed startup that received its first government contract through the Open program in 2019. By 2024, it had secured over $750 million in defense contracts and was selected as one of two companies to manufacture collaborative combat aircraft, beating traditional prime contractors like Boeing and Lockheed Martin.

Broader implications for innovation procurement

The Air Force’s Open reform is not a one-off. In fact, it has become a poster child for similar programs across and beyond the DoD. By the end of 2022, seven of the 11 agencies that participate in SBIR had Open topics, and at those agencies the Open topics composed on average of 40% of all awards. Today, the Air Force is pursuing an 80% to 20% budgetary split between Open and Conventional awards. And in 2022, Congress legislated that every part of the DoD must conduct Open SBIR solicitations. Outside the SBIR, governments around the world, including in the EU and UK—as well as other U.S. agencies such as DARPA, the NIH, and DoE—have sourced innovative ideas from firms via open solicitations.

The Open approach enables firms to identify technological opportunities about which the government is not yet fully aware.

Our results have informed and validated these policy changes. Furthermore, our findings have implications beyond defense. Open innovation may be particularly suited to technologies that are more modular, have lower barriers to entry, and benefit from civilian innovation ecosystems. This aligns with the shifting frontier of military technology from highly integrated, capital-intensive platforms toward technologies with strong civilian applications.

This article summarizes “Opening up Military Innovation: An Evaluation of Reforms to the U.S. Air Force SBIR Program”, by Howell, Sabrina, Jason Rathje, John Van Reenen and Jun Wong, in the Journal of Political Economy.

Sabrina Howell is at New York University. Jason Rathje is in the U.S. Air Force. John Van Reenan is at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Jun Wong is at the University of Chicago.

References

Belenzon, Sharon, and Larisa C. Cioaca (2024) “Guaranteed Markets and Corporate Scientific Research.” NBER Working Paper No. 28644

Howell, Sabrina, Jason Rathje, John Van Reenen and Jun Wong (2025), “OPENing up Military Innovation: An Evaluation of Reforms to the U.S. Air Force SBIR Program”, forthcoming Journal of Political Economy

Howell, Sabrina (2017) “Financing Innovation: Evidence from R&D Grants.” American Economic Review, 107 (4): 1136–64.

Bloom, Nick, Chad Jones, John Van Reenen and Michael Webb (2020), “Are ideas becoming harder to find?” American Economic Review 110(4): 1104–1144