Summary

Large companies sometimes buy innovative smaller firms and then terminate their projects. Our recent study calls these “killer acquisitions”. We consider the pharmaceutical sector and investigate whether companies ever seek to eliminate competing therapies under development. There is clear evidence that such acquisitions have indeed arisen in recent decades. They are likely to lessen competition, increase prices, and discourage the emergence of better treatments for patients.

We first develop a theoretical model to analyze killer acquisitions, and then study their prevalence in pharmaceutical drug development. This sector is especially well suited to empirical analysis, because we can use development information on more than 16,000 drug projects originated by more than 4,000 companies. We find that drug projects acquired by incumbent firms with a closely related existing drug – one that treats the same disease with the same mechanism of action – are almost 23% less likely to continue in development after an acquisition, compared to otherwise similar drugs acquired by non-overlapping incumbents. Importantly, we show that several alternative explanations for these acquisitions can be ruled out, and the effect is even larger when competition is limited.

Our estimates indicate that, conservatively, 5.3% to 7.4% of acquisitions in our sample are in the “killer” category. These disproportionately arise just below thresholds for antitrust scrutiny in the United States. The results suggest that antitrust policy should scrutinize closely the impact of acquisitions on corporate innovation, and especially those which plausibly work against the development of future competing products. When such deals routinely appear to avoid regulatory scrutiny, through acquisitions of entrepreneurial ventures at transaction values lower than review thresholds, this should be a concern. Our findings are drawing the attention of policymakers and antitrust regulators around the world.

Main article

Large companies sometimes buy innovative smaller firms and then terminate their projects. A recent study calls these “killer acquisitions”. The authors consider the pharmaceutical sector and investigate whether companies ever seek to eliminate competing therapies under development. There is clear evidence that some acquisitions do indeed fall into this category. Killer acquisitions could pose a problem for health policy, when they lessen competition, increase prices, and discourage the emergence of better treatments for patients. This form of acquisition raises new questions for antitrust, and the research described here is now drawing attention from competition authorities around the world.

Innovation matters because it drives economic growth, increases profits, and can often make consumers better off. Innovating firms are sometimes taken over by incumbents, typically while the innovating firm remains in the early stages of product development. Economists have traditionally viewed these deals quite positively as a routine part of overall growth. Established firms which are good at exploiting technologies may buy innovative targets to take advantage of synergies. This could enable specialization and increase innovation, profits, and consumer welfare.

“A large firm may buy an entrepreneurial startup in order to shut down the target firm’s projects before they become a competitive threat.”

But some observers have speculated that an alternative, more pernicious, motive may be at work. A large firm may buy an entrepreneurial startup in order to shut down the target firm’s projects before they become a competitive threat. We call these “killer acquisitions” because they eliminate promising, but competing, innovation. The research described here analyzes this strategy and finds that it has played a significant role in the pharmaceutical industry in recent decades.

Theory

Our research starts with a theoretical analysis, in which we study killer acquisitions as a general phenomenon. We consider acquisitions of an innovative target firm (or entrepreneur) with a project still under development. Further costly development would be needed for a product to be brought to market, and the ultimate project success is uncertain: the project might fail before the product reaches the market. We show that an incumbent acquirer has weaker incentives than an entrepreneur to continue developing a project, if the new project overlaps with the incumbent’s existing product portfolio. This is a version of a well-known result, the “replacement effect” identified by the economist Kenneth Arrow in 1962. He examined “the monopolist’s disincentive created by his preinvention monopoly profits” (Arrow, 1962, p. 622).

Perhaps surprisingly, the disincentive to innovate can be so strong that an incumbent firm may buy an innovative startup simply to shut down its projects. In this way, the incumbent tames the “gale of creative destruction” associated with innovation (Schumpeter, 1942). A killer acquisition motive can arise whenever there is some degree of buyer/ target overlap, so that the target firm might be a competitive threat in the future. We also show that competition, now or in the future, diminishes the incentive for killer acquisitions. This is because competition lowers the rents that dominant incumbents would otherwise seek to protect.

“A killer acquisition motive can arise whenever there is some degree of buyer/ target overlap, so that the target firm might be a competitive threat in the future.”

Our analysis suggests that killer acquisitions can arise even when the entrepreneur’s new project is higher quality than the incumbent’s existing projects or products; even when incumbents can benefit from development synergies relative to the entrepreneur, such as advantages in developing the acquired projects; and even when there are multiple potential buyers engaged in a bidding war.

Evidence

Our theoretical insights into killer acquisitions could apply across many industries, whenever innovative startups threaten dominant incumbents. Investigating this phenomenon, however, presents several challenges. We need to observe project-level product development activity, and track projects as they move across firms due to acquisitions. We also need accurate measures of overlap between the buyer’s portfolio and the target firm’s development project, and the extent of competition in the relevant product market.

To address these challenges, we study pharmaceutical drug development, a highly innovative sector and a socially valuable activity. We collect detailed development information on more than 16,000 drug projects originated by more than 4,000 companies, where the projects were initiated between 1989 and 2010. We follow each drug from initiation, flagging any acquisition, and observe development milestones of drug projects independently of project ownership, meaning we follow the same projects before and after an acquisition.

We find that drugs under development are less likely to be developed further when acquired by firms with overlaps in the product market. In particular, drug projects acquired by incumbent firms with a closely-related existing drug – one that treats the same disease with the same mechanism of action – are about 23% less likely to continue in development after an acquisition, compared to otherwise similar drugs acquired by non-overlapping incumbents.

“We also show that competition, now or in the future, diminishes the incentive for killer acquisitions.”

We also document that, for already-approved drugs that face little existing competition, acquisitions lower the development rates of new drugs to an even greater extent: development is about 40% less likely, under the same comparison reported above. That is to say, in markets where incumbents can already exercise substantial market power because they do not face any competition, or have just one direct competitor, buying and terminating new drug innovation is even more common.

There is also evidence that, when the incumbent’s drug is far from patent expiration – and thus generic competition is still several years away – incumbents have a stronger incentive to acquire and terminate innovative projects. In particular, the effect on development rates is concentrated in those acquisitions where the patent on the buyer’s overlapping drug is still more than five years from expiration, and thus currently protected from the entry of generic competitors.

Are there alternative explanations?

To examine the robustness of our findings, we consider several other empirical models, subsamples, and data analyses. We find that diminished development for overlapping acquired projects, after acquisition, appears to be driven by drugs that see no further development activity after acquisition – in other words, by immediate and permanent terminations. Projects acquired by overlapping incumbents are about 21% more likely to cease development immediately, compared to those acquired by non-overlapping incumbents. Further, there is no evidence that acquiring firms purposefully delay development or are simply slower at developing overlapping projects.

Importantly, our work does much to rule out several alternative explanations for the empirical results. The first is optimal project selection: for multi-project targets, perhaps the buyer intends to pursue only the most promising projects, while discontinuing those that seem less promising. Our results continue to hold in the subsample of acquisitions of single-drug companies, however. This suggests that optimal project selection does not explain our main results.

A second alternative explanation might be the redeployment of intellectual capital, in which the buyer wants to secure, and redeploy to more productive uses, the target’s underlying technology. In this case, the inhibited development of overlapping acquired projects could be a by-product of redeployment. To explore this, we study the chemical similarity of acquired drugs to the projects of the buyer before and after acquisition. We find no evidence to support the idea that acquired technologies are integrated into the new drug development projects of the buyer. Nor do we find that buyers are more likely to cite the patents of acquired projects.

“Killer acquisitions are socially costly and reduce the range of treatments available to patients.”

Third, we ask whether there is redeployment of human capital. Some acquisitions that look like development-killers may not be: instead, incumbents may be seeking to employ the innovators at the target company for other projects. Again, project terminations would be a by-product of wider goals. To explore human capital redeployment, we examine inventor mobility and productivity around acquisition events. We show that, ultimately, only 22% of inventors from target firms work for the acquiring firms. Nor do those inventors become more productive after acquisitions. These results are inconsistent with explanations in terms of technology or human capital redeployment.

A fourth alternative explanation could be “salvage” acquisitions, in which overlapping firms buy already-failing targets to secure the target’s valuable assets cheaply. Following this logic, inhibited development would arise before the relevant acquisition. But we find no evidence that overlapping acquisitions see either pre-acquisition declines in development or lower valuations, on average, compared to non-overlapping acquisitions.

Policy implications

In the pharmaceutical industry, incumbents often seek to make acquisitions when the target’s technology or project is still at a nascent stage. As a result, some of these deals are exempted from the pre-merger review rule of the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), under the Hart-Scott-Rodino (HSR) Antitrust Improvements Act of 1976. This exemption arises when takeovers fall below a certain size threshold. To further examine the claim that killer acquisitions are the driving force behind our empirical results, we present evidence that incumbent buyers conduct overlapping acquisition deals that do not trigger FTC reporting requirements under HSR, and thereby avoid antitrust scrutiny. This is because such transactions involve target firms without meaningful physical assets and revenue.

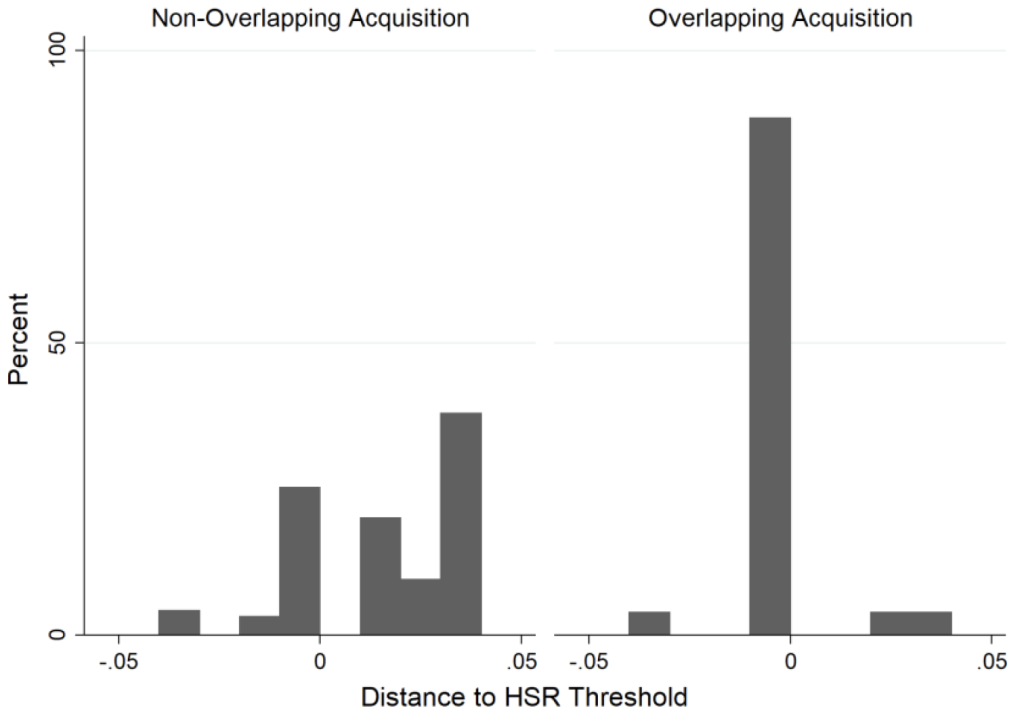

We show that the eventual drug launch rates of transactions just above and just below these reporting thresholds are vastly different. Whereas 9.1% of acquired drug projects just above the threshold eventually reach the market, only 1.8% of acquired drug projects just below the threshold do so. Moreover, acquisitions where incumbents buy innovating firms with drug projects that treat the same diseases as the incumbent’s drugs – and with the same mechanism of action – disproportionately bunch just below the HSR deal size reporting thresholds. In contrast, we detect no such bunching for non-overlapping acquisitions, as shown in Figure 1.

Conclusions

Our estimates indicate that, conservatively, 5.3% to 7.4% of acquisitions in our sample are in the “killer” category. These disproportionately occur just below thresholds for antitrust scrutiny. The extent of lost innovation is substantial. The estimates imply that, without killer acquisitions, the number of drugs being developed in the United States would be more than 4% higher each year. Killer acquisitions are socially costly and reduce the range of treatments available to patients.

“The force of the Schumpeterian gale of creative destruction… may be less potent than previously thought.”

Given these costs, our findings have drawn the attention of policymakers and antitrust regulators around the world. They have been cited in the White House Executive Order on Promoting Competition; the United States House Antitrust Report on Competition in Digital Markets; and by the FTC as an example of non-reportable consolidation under the Hart-Scott-Rodino Act. The European Parliament recently voted in favor of the Digital Markets Act, which cites our work and aims to limit killer acquisitions. The German and Austrian antitrust authorities have updated their merger control rules to include transaction value as a consideration. In response to our work, there have also been calls for China’s merger control threshold to be revised. All of these citations can be found in online sources at the links provided below.

Our results suggest that antitrust policy should continue to scrutinize closely the impact of acquisitions on corporate innovation, especially when they plausibly work against the development of future competing products and technologies. The fact that such deals routinely appear to avoid regulatory scrutiny, through acquisitions of entrepreneurial ventures at transaction values below the HSR review thresholds, exacerbates the concern.

We end with another observation. The force of the Schumpeterian gale of creative destruction—whereby the inventions of “young” firms sweep away entrenched and less innovative incumbents—may be less potent than previously thought. In the United States, innovation and the share of young firms in economic activity have declined over time (Akcigit and Ates 2021). This is not only because incumbents are more reluctant to innovate, but also because incumbent firms with market power have sometimes bought innovators to eliminate future competition. In so doing, they are likely to have strengthened their position, at the cost of weakening the overall rate of technological progress.

This article summarizes ‘Killer Acquisitions’ by Colleen Cunningham, Florian Ederer and Song Ma, published in the Journal of Political Economy in 2021.

Colleen Cunningham is at the London Business School. Florian Ederer and Song Ma are both at the Yale School of Management.