Summary

Why do employers lay off workers without giving them the option to keep their jobs at a lower wage? New research uses an innovative survey of the recently unemployed to gather the views of workers on this question. The findings are striking: many workers would have accepted significant pay cuts in order to keep their jobs, and yet few employers discuss cuts in pay, benefits, or hours as alternatives to layoffs. Based on the survey results, about a quarter of the layoffs could have been avoided, in the view of workers, by wage cuts that workers would have been willing to accept. These results, for the state of Illinois in the US, suggest that supporting such negotiations could bring major social benefits, by saving jobs and reducing unemployment insurance claims. More research is needed into how policymakers, institutions, and management practices can foster constructive discussions over wage cuts as an alternative to layoffs.

Economists have long known that wages are “sticky”, in that they are often slow to change. But even so, a worker and employer might still agree to a new, lower wage when necessary to save a job that benefits both. Surprisingly little is known about how workers view such pay cuts as an alternative to layoffs, and so the research summarized here investigates this question. The researchers surveyed the recently unemployed – more precisely, those newly claiming unemployment insurance – in Illinois in autumn 2018, a time of low inflation and low unemployment. Even though the economy was strong, most new unemployment insurance (UI) recipients said they would have accepted wage cuts of 5-10 percent to stay on their job for another 12 months. Remarkably, one third would have accepted a 25 percent cut in pay.

Yet employer-worker discussions about cuts in pay, benefits, or hours as alternatives to layoffs are rare. Fewer than 3 percent of the job losers in the sample report such discussions. Actual pay cuts before job loss are also rare: Fewer than 1.5 percent of job losers had a wage cut in the twelve months before their layoff. When asked why firms do not engage in these discussions, nearly two-fifths of the survey respondents said they didn’t know; another 36 percent thought pay cuts would not save their jobs; and 16 percent said that pay cuts would undermine morale or lead the best workers to quit.

The researchers then use their survey data to look for job-saving pay cuts, both small enough to be acceptable to the job loser and large enough (in the worker’s estimation) to save the lost job. The share of permanent layoffs satisfying both conditions ranges from 23 percent at a 5 percent wage cut, to 12 percent at a 25 percent wage cut. Since many layoffs could be avoided by pay cuts of the right size, researchers and policymakers should consider how to support such negotiations, thereby saving jobs and reducing the need for UI claims. A rough calculation for California suggests that UI benefit payments could be reduced by about $1.5 billion per year.

Main article

Could pay cuts save some jobs? This question is hard to answer, for at least two reasons. First, widespread evidence of wage “stickiness” is not enough to imply that rigid wages are a factor in layoffs. Put simply, even when wages rarely change, the worker and employer might still agree to a new, lower wage when necessary to save a job that benefits both. This view, espoused by Barro (1977) among others, is called the “efficient separations hypothesis”. Second, although some economists have considered why wages might be inefficiently rigid at the point of separation, the relevant theories are hard to test. Surveys reveal that some employers hesitate to cut wages due to concerns about negative effects on morale and productivity, but the literature has been silent on how workers regard pay cuts as an alternative to layoffs.

To elicit the views of workers, we carried out an innovative survey of new unemployment insurance (UI) recipients. Most UI recipients express a willingness to accept wage cuts of 5-10 percent to stay on their job for another 12 months. Remarkably, one third would accept a 25 percent cut in pay. Yet we also find that worker-employer discussions about cuts in pay, benefits, or hours, as an alternative to layoffs, almost never happen. Moreover, we find that about a quarter of the layoffs in our sample are bilaterally inefficient: there is a pay cut both small enough to be acceptable to the job loser and large enough to save the job (in the worker’s perception). Our survey is the first to document the striking disjunction between worker-side openness to wage cuts and a widespread reluctance of employers to even broach the subject. Ours is also the first study to test the efficient separations hypothesis directly, one layoff at a time.

The literature has been silent on how workers regard pay cuts as an alternative to layoffs.

Our survey of unemployment insurance recipients

We survey people who began collecting UI benefits in Illinois from 10 September 2018 to 24 November 2018, a period of low and stable inflation and low unemployment. Our Entry Survey asks about demographic characteristics, the lost job, willingness to accept pay cuts instead of a layoff, whether workers discussed such cuts with their former employer, the reasons for employer reluctance to offer such deals, and more. We tailor the questionnaire separately for permanent and temporary layoffs. The survey invitation went to UI recipients the day after they received their first unemployment benefit payment.

As shown in Davis and Krolikowski (2025), the survey yields meaningful data on the labor market opportunities of UI recipients, their willingness to accept pay cuts to save jobs, and their future wages once employed again. In terms of demographics, the survey sample is similar to that of all newly unemployed job losers in the Current Population Survey in the same period.

Would workers accept pay cuts to save jobs?

Table 1 shows that many workers would accept pay cuts to save jobs. Sixty percent of UI recipients on permanent layoff say they would have accepted a pay cut of 5 percent to stay on their previous job for another 12 months, and more than half would have accepted a 10 percent cut. One third would have accepted a pay cut of 25 percent. Among UI recipients on temporary layoff, 55 percent would accept a 5 percent cut to keep working, and more than one third would accept a cut of 20 or 25 percent. These results hold at a time of near-full employment. Presumably, the willingness to accept pay cuts would be even greater in a weaker economy. Davis and Krolikowski (2025) also show that job losers who had been earning high wages, compared to observationally similar workers, were much more willing to accept pay cuts to save their jobs.

Table 1: Percent of UI recipients who would have accepted a pay cut

| Size of proposed pay cut | 5% | 10% | 15% | 20% | 25% |

| Permanent layoffs | 60.6 | 52.3 | 43.7 | 38.4 | 32.4 |

| (2.4) | (2.5) | (2.5) | (2.4) | (2.3) | |

| Observations | 404 | 413 | 410 | 419 | 423 |

| Temporary layoffs | 54.5 | 42.9 | 35.8 | 34.3 | 37.4 |

| (5.0) | (5.0) | (4.9) | (4.7) | (4.9) | |

| Observations | 101 | 98 | 95 | 102 | 99 |

Note: Standard errors are in parentheses. For permanent layoffs, we asked: “Would you have been willing to stay at your last job for another 12 months at a pay cut of X percent?”

For temporary layoffs, we asked: “Suppose your employer offered a temporary pay cut of X percent as an alternative to the temporary layoff. Would you have been willing to accept the temporary pay cut to avoid the layoff?”

Pay cuts to save jobs are rarely discussed

The willingness of workers to accept job-saving wage cuts is even more striking when coupled with our next finding: Employer-worker discussions about cuts in pay, benefits, or hours as an alternative to a layoff are exceedingly rare. Fewer than 3 percent of the job losers in our sample report such discussions. This pattern holds across industries, job tenure categories, education categories, firm size categories, for union and non-union workers, and by reason for layoffs. These discussions are rare even for job losers who express a willingness to accept large pay cuts.

Our survey is the first to document the striking disjunction between worker-side openness to wage cuts and a widespread reluctance of employers to even broach the subject.

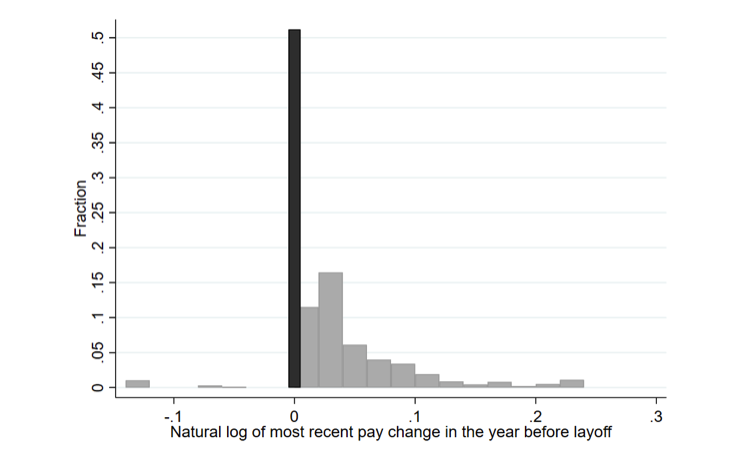

Moreover, actual pay cuts before job loss are also rare among UI benefit recipients. Figure 1 makes this point by displaying a histogram for the distribution of changes in log hourly wages in the twelve months before job loss. Fewer than 1.5 percent of job losers had a wage cut in the twelve months before their layoff. More than half experienced no wage change in the twelve months before layoff, and 46 percent received a nominal wage increase.

Because we surveyed UI recipients, workers whose jobs were recently saved by wage cuts are not in the sample. Nevertheless, our results support the claim that job-saving wage cuts are rarely discussed. In this regard, we make two observations: First, unsuccessful discussions about pay cuts to save jobs are captured by our sample frame. Our results imply that successful discussions are either many times more common than unsuccessful ones, or that successful ones are also rare. Second, some successful efforts to implement job-saving pay cuts will be captured by our frame indirectly. If a wage cut first preserves an employment relationship, but later developments lead to layoff, that layoff will be observed for job losers that claim UI benefits. So, our survey captures UI benefit recipients who experienced a pay cut in the twelve months before job loss. But Figure 1 implies that this outcome is also rare.

Figure 1: Bar chart of log wage changes over year before job loss

Questions: “When was the most recent change to your pay or benefits on your previous job?” and “How much did your salary or hourly wage change?”

Note: We consider individuals with at least one year of tenure on their lost job, omit observations for which the hourly or reservation wages are below $2 or above $200, and “winsorize” changes in log wages at the 1st and 99th percentiles. The black bar refers to those with no prior change in compensation on the lost job. Gray bars, with a bin width of 0.2, refer to those with a pay change during the twelve months before job loss.

Why are wage cuts rarely discussed, according to workers?

If the respondent had no discussion with their former employer about job-saving compensation cuts, we ask: “If you had to guess, why do you think your employer did not discuss any kind of cuts in pay, benefits or hours?” In response, nearly 40 percent of UI recipients say they don’t know. Another 36 percent think pay cuts would not save their jobs, and 16 percent say pay cuts would undermine morale or lead the best workers to quit. For those who lost union jobs, 45 percent say contractual restrictions prevent wage cuts.

Sixty percent of UI recipients on permanent layoff say they would have accepted a pay cut of 5 percent to stay on their previous job for another 12 months…One third would have accepted a pay cut of 25 percent.

In contrast, few job losers point directly to company pay scales as a source of wage rigidity for firms making layoff choices. We also find only a very minor role for minimum wage and benefit laws as a source of downward wage rigidity among UI benefit recipients.

How many layoffs could be avoided by pay cuts?

We use our survey data to look for job-saving pay cuts that are both small enough to be acceptable to the job loser and large enough (in the worker’s estimation) to save the lost job. This combination violates the condition for bilaterally efficient separations that holds in many leading economic theories of layoffs, frictional unemployment, and job ladders.

Table 2 reports the share of permanent layoffs that satisfy both conditions by size of proposed wage cut, which varies randomly across survey respondents. This share ranges from 23 percent at a 5 percent cut to 12 percent at a 25 percent cut. In Davis and Krolikowski (2025) we examine the robustness of these findings in more detail. We find that at least 12 percent and at most 35 percent of layoffs violate bilateral efficiency. In short, our results indicate that many layoffs could be avoided by pay cuts of the right size.

Table 2: Estimated percent of permanent layoffs that violate bilateral efficiency

| Size of Proposed Pay Cut | 5% | 10% | 15% | 20% | 25% |

| Percent Violating Bilateral Efficiency | 23.0 | 16.0 | 18.1 | 13.2 | 12.3 |

| Observations | 391 | 401 | 404 | 408 | 415 |

Note: The first row reports the percent of respondents who say the proposed wage cut is small enough to be acceptable to them and large enough to save the job. Recall that nearly 40 percent of job losers “Don’t know” why their employer did not discuss wage cuts as an alternative to layoff. If they knew, they might say the proposed wage cut would not save their lost job. In this table, we assume that the share of proposed wage cuts that “Would not prevent layoff” is the same for “Don’t know” and “Do know” cases (62 percent).

The main caution here is that our estimates for avoidable layoffs rely on worker assessments of whether the proposed wage cuts would lead the employer to forgo layoffs. Worker perceptions in this regard may diverge from employer views. In future work, we plan to implement a two-prong survey design that asks job losers and their former employers about the same layoff and wage-reduction events. This design will yield sharper inferences about why layoffs happen and whether, and how, they might be avoided. It will also let us uncover and explore any divergence of views between workers and employers.

Policy implications

Our results are relevant for policymakers in at least two ways. First, our results suggest that efforts in the US to support compensation negotiations could ease the fiscal strain on state UI trust funds, by averting layoffs and reducing the number of persons drawing UI benefits. Fiscal benefits of this sort would not come at the expense of workers or firms. The savings would be especially valuable for the many states that face solvency issues with their UI trust funds. For example, back-of-the-envelope calculations using our estimates suggest that California could reduce UI benefit payments by about $1.5 billion per year with successful compensation negotiations that avert layoffs and initial UI claims.

Our results indicate that many layoffs could be avoided by pay cuts of the right size.

Second, we need research into how policy changes, institutional reforms, and management practices can foster constructive discussions about pay cuts as alternatives to some layoffs. Previous work suggests that pay cuts – and even just proposing them – can lower morale, reduce productivity, and harm product quality. But there are also examples of large, permanent wage cuts that have not yielded persistent and material declines in productivity, as for airline pilots after the 9/11 terrorist attacks. Earlier research suggests that compensation negotiations are more fruitful when workers and employers trust each other, and employers successfully manage wage expectations. Third-party mediators could help with trust-building and communications, perhaps combined with other resources that US states already provide, via Rapid Response teams, to workers at establishments that anticipate mass layoffs.

Overall, this line of survey research can provide stronger foundations for how economists think about wage rigidity and layoffs. It may also yield insights into how managerial practices, third-party mediation efforts, and policy changes can reduce the frictions – in communication, coordination, and contracting – that inhibit wage adjustments for firms considering layoffs. Such insights could reduce the number of layoffs and ease the fiscal strains on the unemployment insurance system.

This article summarizes “Sticky Wages on the Layoff Margin” by Steven J. Davis and Pawel M. Krolikowski, published in the American Economic Review in February 2025.

Steven Davis is the Thomas W. and Susan B. Ford Senior Fellow and Director of Research at the Hoover Institution, and Senior Fellow at the Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research (SIEPR).

Pawel Krolikowski is a Senior Research Economist at the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland.

Reference

Barro, R. J. (1977). “Long-term Contracting, Sticky Prices, and Monetary Policy,” Journal of Monetary Economics, 3(3), 305-316.

Davis, S. and P. Krolikowski. 2025. “Sticky Wages on the Layoff Margin.” American Economic Review, 115(2) 491-524,