Summary

Each year, foreign multinationals in the United States receive around five billion dollars in economic development subsidies. A common view is that multinational firms can have transformative effects on the local economies in which they locate production. To see whether this is true, a recent study uses U.S. tax records on firms and workers to investigate how the actions of multinational firms affect host locations. The researchers estimate the direct effects of multinational firms on their workers and their indirect effects on other local firms. The typical worker earns 7% more at the average foreign multinational than at the average domestic firm, and every job created by a foreign multinational adds about 0.5 jobs and $139,000 in value added at domestic firms in the same commuting zones.

Local governments often try to lure foreign multinationals to their cities and counties. Employing (anonymized) tax records on firms and workers in the United States, the authors of the new study investigate the direct effects that foreign multinationals have on their own employees, as well as the indirect effects that these firms have on local businesses and their employees.

Data on wage income from tax records reveal that foreign multinationals pay their workers on average 25% higher wages than domestic-owned firms. But this figure may overstate the wage premium paid by foreign multinationals to their workers, as the composition of their employees may be different – for example, foreign multinationals may hire more skilled workers on average, or multinationals may operate in locations or industries that pay higher wages.

To address this problem, the authors study the wage changes of those workers who move jobs between a domestic-owned and a foreign-owned employer, taking into account differences between industries and locations. The researchers find that the typical worker earns a seven percent higher wage at a foreign-owned firm. This wage premium is similar to the one a worker earns when moving from a domestic non-multinational firm to a domestic-owned multinational firm. The latter finding suggests that it is not foreign ownership as such that is behind the multinational wage premium, but rather membership in a multinational production network.

It is useful to know the direct wage effect for the average worker, but the foreign multinational wage premium varies widely across types of workers. The authors develop an approach which allows the foreign multinational wage premium to vary by the level of worker skill. They measure the skill of a worker from her earnings after allowing for systematic differences between locations, industries, and firms. They find that the multinational wage premium is essentially zero for the lowest decile of worker skills, rising to 21 percent for workers in the top decile of worker skills.

The authors also allow the multinational wage premium to vary with a firm’s country of origin. They find that the average skill of workers and the wage premium rise with the GDP per capita of the country of foreign ownership. Norwegian-owned firms, for example, pay an average wage premium of 15 percent, whereas the wage premium at Chinese-owned firms in the United States is actually negative: on average, a U.S. worker earns four percent more at a U.S. owned firm than at a Chinese-owned firm.

The authors also estimate the effects of foreign multinationals on other domestic firms and their workers in the same local area. A key challenge in estimating such effects is that foreign firms have chosen where to locate, and their choices may be correlated with local conditions in ways that could undermine a statistical analysis. To address this problem, the authors exploit geographical variation in where firms from a given country locate, together with variation over time in the overall expansion or contraction of firms from a given country. The authors find that an increase in foreign-owned firm activity has positive effects, on average, on domestic-owned firms: their value added and employment both increase, despite the increase in local labor market competition. Workers at domestic-owned firms also benefit, especially those that are more skilled.

Main article

Foreign multinationals account for a sizable fraction of value added, exports, and R&D in the U.S. (Bureau of Economic Analysis, 2017). These firms are affected by regulations on foreign investment, trade policies, and local subsidy competition. A widely-held belief is that attracting a foreign multinational to a location will bring major benefits for local workers and firms. But reliable evidence has been hard to obtain, due to a lack of data and challenges in separating causation from correlation. The key questions for policymakers and local stakeholders center on the direct and indirect effects of a job created by a foreign multinational: How much more does a worker earn when she is hired by a foreign multinational? How are domestic firms and their workers in nearby locations affected by foreign firms?

Data and Statistical Patterns

The new study is the first to construct a panel data set linking all firms and workers in the U.S. with foreign ownership information on firms. To do so, we developed a worker-firm panel from the population of annual U.S. Treasury tax filings from 1999 to 2017. For each worker-firm-year combination, W-2 tax forms provide information on earnings, the firm’s employer identification number (EIN, which is masked to us), and the worker’s residential ZIP code. The sample used for the analysis focuses on workers between ages 25 and 60 at their primary employer. For each firm-year combination, we have information on value added and the 6-digit NAICS industry code, where value added equals sales minus the materials costs of goods sold. Foreign ownership is indicated by the filing of Form 5472, which is the information return for a U.S. corporation that is 25 percent or more foreign owned and includes the country of foreign ownership. We link worker tax data to firm tax data using the EIN.

Using this data, we find that the average worker earns 75,700 USD at foreign firms and 60,700 USD at domestic firms as of 2015, indicating 25 percent higher wages at foreign firms. Comparing the data to three long-term surveys available from the Bureau of Economic Analysis, we note the striking rise in the importance of foreign-owned firms in the U.S. labor market: only 2 percent of workers were employed by foreign-owned firms in the late 1970s, compared to 6 percent today. Spatially, we find particularly high levels of employment at foreign firms along the East Coast and in Rust Belt cities in Indiana, Michigan, and Ohio, but especially low levels in the South. Between 2001 and 2015, major changes have taken place across the U.S., with Gulf Coast states such as Alabama, Louisiana, and Mississippi seeing especially rapid growth, while parts of the East Coast and the Rust Belt have seen sharp declines in the share of foreign employment.

Direct Effects: Methods

The first goal of the new study is to identify the direct effect of foreign multinationals on the wages of their own workers. A “foreign firm premium” in wages has long been posited, such that a given worker would earn more if employed by a foreign firm rather than a domestic firm. As noted above, a first look at the data suggests that the average wage is 25% higher at foreign firms. But this figure may overstate the true foreign firm premium for a given worker, because foreign and domestic firms employ different types of workers; in particular, foreign firms may hire more skilled workers, on average, than domestic firms. Thus, the primary challenge in studying the direct effects of foreign multinationals on their workers’ wages is to disentangle the two, and see whether higher wages at foreign-owned firms are due to a genuine foreign firm premium rather than differences in worker skills.

To estimate how much more a given worker would earn if employed by a foreign firm, we take advantage of the panel data set. Although the tax data are anonymized, the data set can be used to track wages over time, as workers move from job to job. Intuitively, the foreign firm premium can be recovered as the average wage change observed when a worker moves from a domestic firm to a foreign firm, controlling for variation in wages that can be explained by industries or locations. In practice, we implement this using an approach that accounts for many systematic differences in fixed characteristics of individual firms. We use this approach to estimate firm premiums for foreign multinationals, as well as domestic multinationals for comparison.

Direct Effects: Findings

Using this approach, we find that the average firm premium is 7.2 percent at foreign multinationals and about 8.4 percent at domestic multinationals. The contrast with the first look at the data shows the importance of differences in skills. At both foreign and domestic multinationals, about two-thirds of the wage differential that cannot be explained by observable factors is due to a greater share of high-skill workers at foreign multinationals relative to domestic non-multinationals.

We also find that average firm premiums and worker compositions of foreign and domestic multinationals track one another closely across the firm size distribution. The results suggest that belonging to a multinational network, rather than simply being foreign, is the main driver of the foreign firm premium. Furthermore, the multinational wage premium appears to be highest when comparing small foreign firms to small domestic firms.

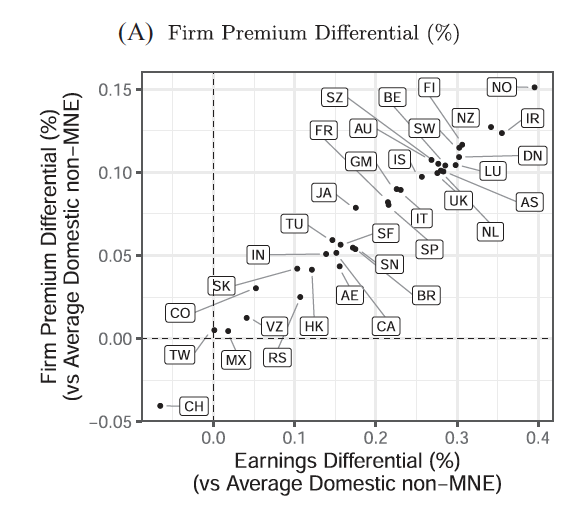

Importantly, the U.S. tax data contain enough unique firms from a large number of foreign countries to estimate country-specific foreign firm premiums. Figure 1 plots the mean firm premium estimate – for the 34 countries of ownership with the most firms – against mean log earnings, where mean log earnings is normalized to be zero at domestic non-multinational firms. We find that the firm premium varies widely by country of origin. The Northern European countries of Denmark, Finland, Norway, and Sweden have larger than average firm premiums, as do Ireland and New Zealand. At the other extreme, small positive firm premiums are estimated for Colombia, Mexico, Russia, Taiwan, and Venezuela, while a negative 4 percent premium is estimated for China. The share of the wage differential explained by firm premiums is roughly the same across all countries at around 37 percent. This implies that countries that offer higher premiums also attract more talented workers.

Regarding differences in worker skills, we find that both domestic and foreign multinationals hire more skilled workers compared to non-multinationals. The difference in the skill composition holds across the entire firm size distribution, but is especially pronounced when comparing a smaller multinational firm to a non-multinational firm in the same size category.

A natural question is whether high-skill workers or low-skill workers gain the greatest premium when moving to a foreign firm. In an extension to our main analysis, we find that the foreign firm premium is increasing in the skill of workers. Foreign and domestic multinationals both pay about a 20 percent premium to workers in the top skill decile. By contrast, both foreign and domestic multinationals pay workers in the bottom skill decile the same as domestic non-multinationals. These results suggest that multinationals use production methods that make especially productive use of skilled workers. This leads them to demand more high-skill workers and offer higher wage premiums to attract more high-skill workers.

Indirect Effects: Methods

The study also seeks to identify whether employment growth at foreign-owned firms affects the outcomes of local domestic-owned firms. Identifying these indirect effects is more challenging than studying the direct effects. This is due to what economists call a “selection” problem: Foreign firms may choose to hire in regions in which domestic firm outcomes are already set to grow (or decline). A statistical analysis may then conflate the true effect with local conditions that influence location choices. For example, if foreign firms decide to locate mainly in fast-growing areas, it would be easy for researchers to overstate the impact of foreign firm activity on domestic firms, which on average would have grown faster anyway.

To address this problem, we use an idea from the immigration literature (Card, 2001). That literature draws on the fact that immigrants often cluster into U.S. regions based on country of origin, and uses this to isolate “exogenous” or independent local variation in immigration driven by changes in total flows from that country, rather than by local domestic conditions. There is a parallel with employment at foreign-owned firms, which tends to be clustered by region and country of origin. This means that, for example, when German firms increase their aggregate employment in the U.S., this can be used to isolate those local increases in the employment of German-owned firms driven by the overall German expansion, rather than by conditions at that particular location.

In the case of multinationals, Canadian firms are more likely to be near the Canadian border, European firms are primarily engaged in the eastern part of the U.S., and Asian firms account for a large share of foreign-owned firms near the West Coast as well as in the Midwest. There are plausible reasons why firms cluster by nationality: these include spatial variation in the cost of shipping intermediate goods from the home country, or the costs of communication; foreign firms may be more likely to hire employees (in particular, managers) from their country of origin, who may prefer to live near other immigrants from their country; and foreign firms of a particular country of origin may share information about regions of the US. We use this clustering of employment at foreign-owned firms in order to isolate the indirect effects on the local domestic-owned firms, while controlling for local employment conditions.

Indirect Effects: Findings

Using this approach, we estimate the effects of a one percentage point increase in the share of employment at foreign firms in a U.S. commuting zone. This increases the value added, employment, and wage bill at local domestic firms by 0.96 percent, 0.53 percent, and 0.63 percent, respectively. These effect sizes are roughly twice those found using a naïve approach that does not take selection into account. When estimating the effects separately for different types of domestic firms, we find that foreign firms have the greatest impacts on large domestic firms and on domestic firms in the tradable sector.

We also examine indirect effects on earnings at the worker level. Consider a one percentage point increase in the share of employment at foreign firms in a U.S. commuting zone. This increases earnings growth by 0.15 percent among local workers who continue to be employed by local domestic firms. To investigate inequality in the worker-level earnings effects, we split the sample into equally-sized categories by ranking lagged earnings within a given commuting-zone-year combination. A one percentage point increase in the share of employment at foreign firms in the commuting zone results in 0.3 percent wage growth for high-paid continuing workers at domestic firms in the commuting zone, while low-paid workers experience little to no wage growth. Hence, indirect effects primarily benefit high-skilled workers at local domestic firms.

Policy Implications

Policymakers are often confronted with weighing the local economic benefits of a foreign firm against subsidy costs. For the average commuting zone in the U.S., consider the establishment or expansion of a foreign firm that would create 1,000 new jobs. Using our estimate that there is a 7% wage gain for each worker hired by the foreign firm, wage gains for domestic incumbents hired by the foreign firm sum to 4.6 million USD.

To understand the indirect effects, we need to account for both job creation and wage gain effects at local domestic firms. Our indirect effect estimate on employment implies a total local job multiplier of about 1.50: in other words, 0.50 indirect jobs are generated at domestic firms for each job created at a foreign firm. Combining the jobs multiplier effect with the wage gain effects, we estimate a gain of 8.8 million USD for domestic incumbents at local domestic firms, given the 1,000 new jobs at a foreign firm. Combining the direct effect on wages and the indirect effect on employment and wages, we find a total local wage gain of 13.4 million USD, or 13,400 USD per job created at a foreign firm.

Since these are annual gains, we can calculate the discounted presented value and compare it to the typical subsidy cost. We find that the discounted present value of a job created at a foreign firm is equal to the average subsidy cost paid to foreign firms per job if the annual discount rate is 13%. Thus, from the perspective of a local policymaker, the benefits of attracting foreign employers exceed the subsidy cost if the discount rate is below 13% a year. But our calculations suggest that the subsidies given to foreign multinationals for large plant investment or expansions account for a sizable fraction of the net present value of the wage benefits for incumbent workers. Foreign multinationals are mobile in their location choices for large plant openings or expansions; hence it seems natural that, in bargaining with local authorities over large subsidy deals, foreign firms will extract a large fraction of the overall local benefits via subsidy payments.

This article summarizes “The Effects of Foreign Multinationals on Workers and Firms in the United States” by Bradley Setzler and Felix Tintelnot, published in the Quarterly Journal of Economics in 2021.

Bradley Setzler is at the Pennsylvania State University and NBER. Felix Tintelnot is at the University of Chicago and NBER.