Summary

A key policy concern is that the small size of many firms in developing countries may prevent them from adopting technology, and, as a result, leave them stuck in poverty traps. In a new paper, we challenge this view. We show that small firms in urban Uganda engage in active rental markets for large machines between small firms, and that this allows them to access modern machines that have too large a capacity for any single firm.

With BRAC, we conducted a representative survey of about a thousand firms to collect information on the production process for products in sectors that employ a large share of workers in manufacturing. We document three key facts. First, mechanization improves firm productivity. Second, small firm scale limits investment as machines have a capacity that is too high for the typical firm and are very expensive. Third, the rental market for machines helps to overcome these issues of scale; while less than 10% of carpentry firms own a thickness planer, for example, 60% use one.

We usually define the size of a firm as the number of workers employed by the firm owner, but the presence of the rental market suggests that it might be meaningful to redefine a firm as a group of workers sharing the same machines. Once we do so, medium-sized “firms” start to appear: the share of firms with more than ten employees grows from 5% to 33%. Whether or not it is meaningful to define a firm as a machine depends on the size of transaction costs in the rental market, as transaction costs are what creates a boundary between firms.

To understand the impact of transaction costs, we build an equilibrium model of firm behavior and estimate it with our data. We find that the rental market has large aggregate effects. Labor productivity increases by 12%, and the share of firms that are mechanized by 192%, when we move from a situation with no rental markets to one with no rental markets transaction costs. The rental market generates these gains by providing a workaround for market imperfections such as frictions around finance and labor.

How much are these benefits eroded, in practice, by transaction costs? We estimate the real size of transaction costs in our study to be about 40 cents for each dollar spent on renting machines. Our model indicates that an economy with transaction costs of this magnitude would reap more than half of the potential gains of the rental market with no transaction costs. In this sense, transaction costs are relatively limited, and defining a firm as a set of workers sharing the same machines is meaningful.

Our results provide three broad policy lessons. First, providing rental vouchers instead of subsidies to purchase machines can be very effective at increasing mechanization when rental markets are prevalent, as vouchers increase the utilization of existing machines and provide an incentive for firms to invest in more machines. Second, interventions that facilitate capital sharing between firms can be promising, by reducing transaction costs in the rental market. Thirdly, our results highlight the importance of taking into account firm-to-firm interactions within informal clusters—rather than just looking at individual firms—in order to properly understand the barriers to technology adoption in low-income countries.

Main article

We study whether the small size of firms in developing countries prevents adoption of modern and productive machines, thus limiting technology adoption and productivity. Combining a novel survey of manufacturing firms in urban Uganda and a formal economic model, we document how an active rental market for large machines between small firms allows them to collectively achieve economies of scale and mechanize production. These results highlight the importance of taking into account firm-to-firm interactions within informal clusters in order to properly understand the barriers to technology adoption in low-income countries.

Most firms in developing countries employ only a few workers, if any (Hsieh and Olken, 2014). A key policy concern is that their small size may prevent firms from adopting technology: technology is often embodied in large machines, and small firms might not have the scale to justify the investment. As a result, firms may be stuck in poverty traps (Banerjee and Duflo, 2005), which may hinder their mechanization and productivity.

In a new paper (Bassi et al., 2022), we challenge this view. We show that small firms in urban Uganda engage in active rental markets for large machines between small firms, and that this allows them to access modern machines that have too large a capacity for any single firm. The importance of rental markets not only limits concerns related to the small scale of firms, but also provides a valuable policy tool to foster technology adoption and productivity in settings plagued by market imperfections.

Measuring production processes in urban Uganda

Together with BRAC (an NGO), we conducted a representative survey of about a thousand firms in three sectors that employ a large share of workers in manufacturing: carpentry, metal fabrication, and grain milling.

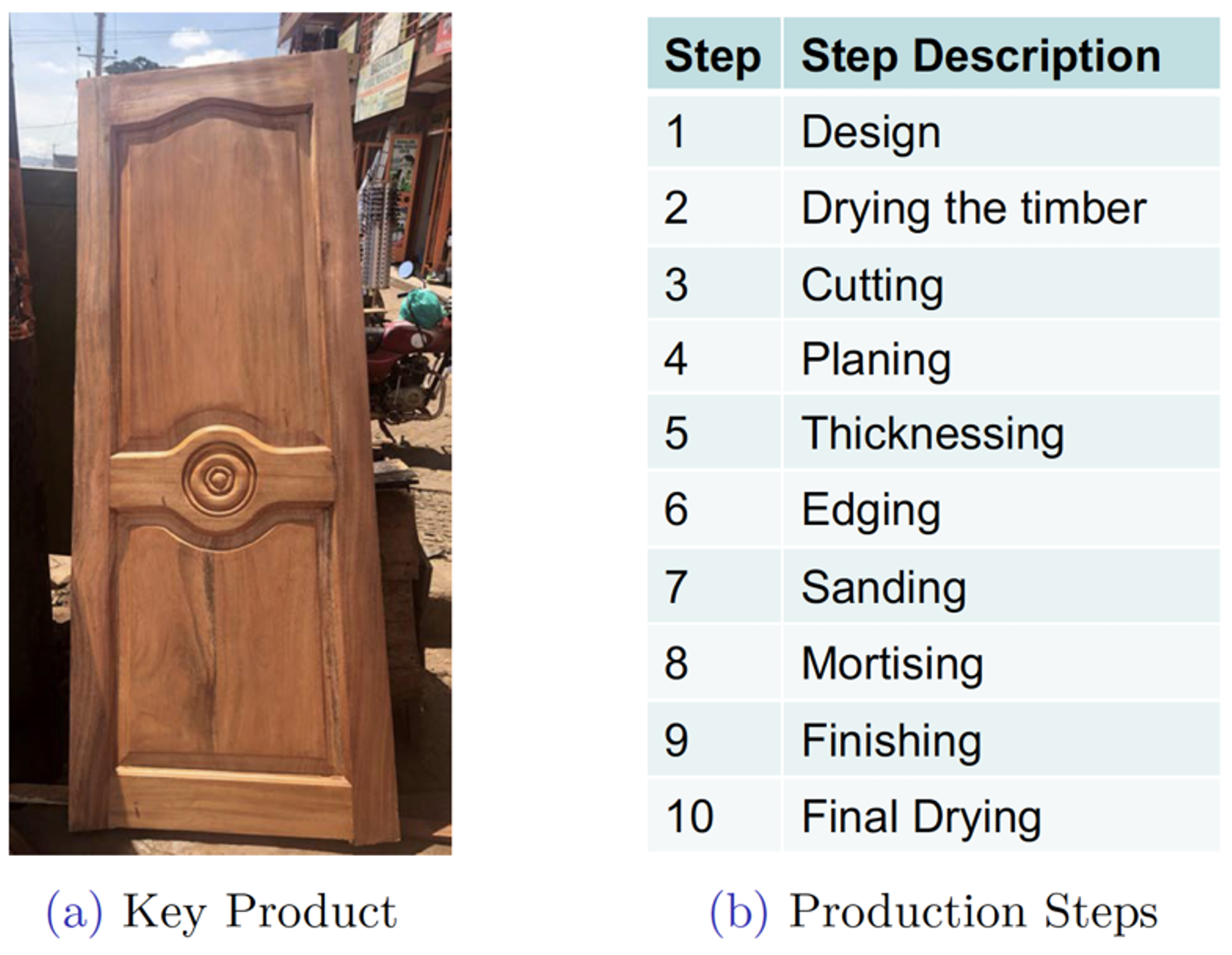

The key innovation of our survey was to collect information on the entire production process for pre-specified products that are common in these sectors. For example, Figure 1 shows our key product for carpentry—a two-panel door—and the steps necessary to produce one. For each step, we gathered information on the combination of labor and capital used, distinguishing between modern machines (e.g., thickness planer) and manual tools (e.g., hand planer). For each modern machine, we know whether it is owned or rented, its value, and the number of hours that the machine is used. For owned machines, we also know if they are rented out to other firms, for how many hours, and at what price.

Figure 1: Key Product and Production Steps in Carpentry

Notes: The left panel shows an image of a two-panel door produced by one of our firms. The right panel shows the list of all the production steps for a two-panel door.

Many small firms operate in informal clusters producing similar products

Using our data, we show that production takes place in informal clusters of small firms, producing similar products with similar production steps. However, firms vary in their mechanization: while some firms use modern machines, others mostly use manual tools and labor. We also document dispersion in size, revenues per worker, and an index of managerial ability constructed using several questions on managerial practices (McKenzie and Woodruff, 2017, who build on Bloom and Van Reenen, 2007).

There are stark differences in mechanization rates across the three sectors: in carpentry, machines are expensive (the average machine costs about seven times average monthly profits), and multiple machines are used in production, each for a few hours. In the other two sectors, machines are cheaper and are used more intensively. Therefore, the rental market may be particularly important in carpentry, where firms are small, but machines are large. Indeed, we find that the rental market is much more prevalent in carpentry, and so this is where we focus our analysis.

Three key facts about mechanization, firm scale and rental markets

We document three key facts on the role of mechanization for productivity, the role of scale for mechanization, and the role of the rental market for machines in carpentry. These are the three facts we target in estimating our model.

- Mechanization improves firm productivity. There is a strong positive correlation between usage of modern machines and firm productivity, as measured by revenues per worker.

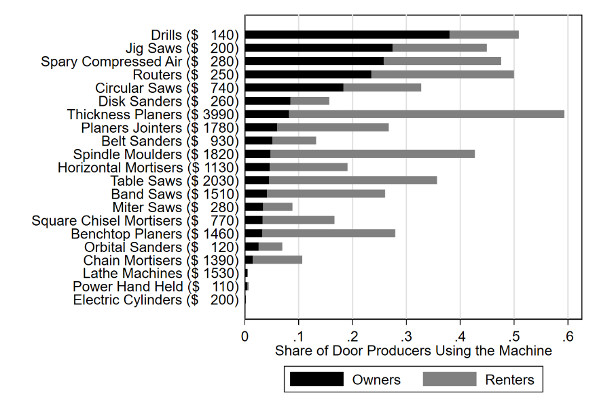

- Small firm scale limits investment. Machines have a capacity that is too high for the typical firm and are very expensive, thus generating sizeable economies of scale. In line with this, ownership rates for most machines are very low: for instance, less than 10% of firms own a thickness planer (Figure 2), which is a key machine in the production process for carpentry. As expected, firms operating at higher scale are more likely to own machines.

- Rental markets for machines help overcome the indivisibility. While ownership rates are low, most firms access modern machines through an active rental market. For example, while less than 10% of firms own a thickness planer, 60% use one (Figure 2). This rental market is between small firms in the same sector, and is possible because the machines are too large even for machine owners, who have excess capacity that can be rented out to other firms nearby.

Figure 2: Usage of Modern machines in carpentry by ownership vs rental

Notes: This figure decomposes the share of door producers in the carpentry sector that use a machine into those firms that own the machine (black) and those that rent it (grey). Sample: Door producers.

A new perspective on the firm size distribution based on the rental market

To appreciate the prevalence of the rental market and how it allows firms to overcome the indivisibility of machines, we show its implications for the firm size distribution. We usually define the size of a firm as the number of workers employed by the firm owner. However, the presence of the rental market suggests that it might be meaningful to redefine a firm as a group of workers sharing the same machines. Once we do so, medium-sized “firms” start to appear: the share of firms with more than ten employees grows from 5% to 33% (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Firm size distribution in carpentry

Notes: The figure shows the firm size distribution in our data according to two alternative definitions: (i) a firm is a manager and his/her workers (dotted grey line); (ii) a firm is a set of workers using the same machines (black line). Sample: Door producers. See Bassi et al. (2022) for further details on how we computed (ii).

Why don’t the more productive firms merge?

Machine owners engage in rental market relationships with smaller firms. Why don’t they take over them instead? There could be many constraints leading to this, such as contracting frictions or limited span of control (Akcgit et al., 2021), which we are not able to study given our data. Through the rental market, however, firms de facto already exploit at least some of the productivity benefits of consolidations, which limits the impact of any such constraints on productive efficiency.

Transaction costs for machine rentals

Is it meaningful to define a firm as a machine? It depends on the size of transaction costs in the rental market, as transaction costs are what creates a boundary between firms and keeps them distinct. Our data shows that the rental market is competitive, but is characterised by transportation and time costs: machines are operated at the premises of machine owners, and so renters have to carry their intermediate inputs to the machine owner and back, and often have to wait for machine access. Using an approach that compares the capital utilization of owners and renters, we estimate the size of these transaction costs to be about 40 cents for each dollar spent on renting machines. An accounting exercise shows that we can explain most of these estimated transaction costs with direct transportation and time costs from our survey.

Modelling firm technology choice in the presence of machine rentals

So, are transaction costs small or large? To answer this question we estimate a model in which carpentry entrepreneurs have some managerial ability and variable costs of capital. They then face two key choices:

- Mechanization choice: whether to mechanise production (i.e., use modern machines) depends on their ability (due to complementarity in production), on the relative productivity of the mechanized process, and on the size of labor market frictions. Large labor market frictions make it difficult for entrepreneurs to expand by hiring labor, and so provide an incentive to substitute labor for machines.

- Investment choice: the relative cost of investing in machines compared to renting them depends on the price of machines and individual cost of capital, on the rental market price, and on the size of rental market transaction costs.

The mechanization and investment choices partition entrepreneurs into machine owners, machine renters, and non-mechanized firms. Within each set, entrepreneurs then choose how much capital and labor to use in production. The rental and output markets are in equilibrium. The rental market is competitive, but subject to the transaction costs.

Aggregate effects of the rental market

The model allows us to quantify the aggregate effects of the rental market and the extent to which these are limited by transaction costs. We calibrate some parameters directly from the data (e.g., machine prices) and estimate the remaining parameters through simulated method of moments.

The rental market has large aggregate effects. Labor productivity increases by 12%, and the share of firms that are mechanized by 192%, when we move from a situation with no rental markets to one with no rental markets transaction costs.

Our benchmark economy, which has transaction costs of about 40 cents per dollar spent in rentals, reaps more than half of these potential gains. In this sense, transaction costs are relatively limited, and defining a firm as a set of workers sharing the same machines is meaningful.

How the rental market shapes the economy

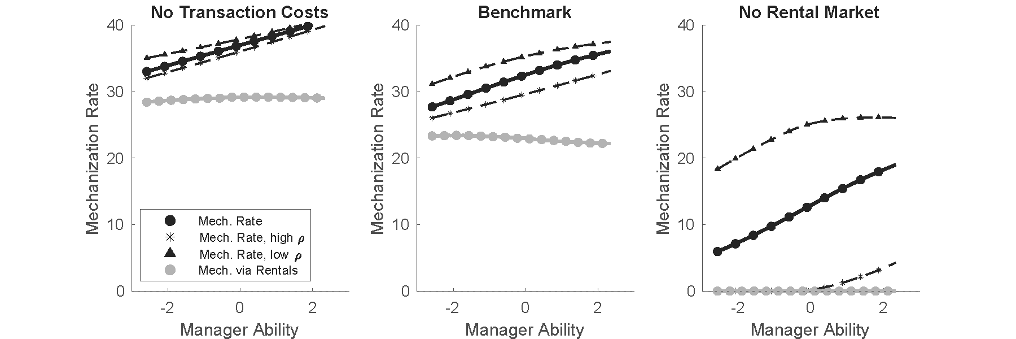

Where are these large gains coming from? The rental market has two principal benefits (Figure 4).

- It allows firms to overcome the capital indivisibility by letting them share large machines, which benefits all firms. Relative to the economy with no rental markets, mechanization rates in the benchmark economy are higher even for high-ability firms, as the possibility to rent out their excess capacity gives them an incentive to invest.

- It unbundles capital ownership and utilization, thus allowing firms with a high cost of capital to mechanize: while the gap in mechanization rates between owners with a high and low cost of capital is large in the economy with no rental markets, this gap is much lower in the benchmark economy. Through this channel, the rental market reduces misallocation.

Figure 4: Mechanization choice and the rental market

Notes: The figure shows mechanisation choices as a function of manager ability and cost of capital . The three panels show three different economies: the estimated one (center), one with no rental market (right), and one with zero transaction costs (left).

The rental market provides a workaround for other frictions that keep firms small

We estimate that firms face substantial frictions in the financial, labor, and output markets. These frictions keep firms small and reduce the correlation between managerial ability, firm size, and productivity. These findings are similarly to those of Bloom et al. (2022) in Mexico. We show that the rental market generates gains by providing a workaround for these market imperfections. The importance of the rental market diminishes as these frictions vanish, and we therefore expect rental markets to matter most in developing countries plagued by market imperfections.

Policy implications: How to help small firms access technology

We can also use our model to discuss the reasons why the rental market is important, and the role of policy. Our results provide three broad policy lessons:

First, rental markets reduce the effectiveness of subsidies to buy machines, such as import subsidies, because firms do not need to buy a machine in order to use it. Providing rental vouchers instead of subsidies can be very effective at increasing mechanization, as they increase the utilization of existing machines by lowering their effective rental cost, and provide an incentive for firms to invest in more machines by increasing demand for rentals. Such vouchers have been considered in the agricultural sector (Caunedo and Kala, 2022) and seem like a promising policy intervention in contexts where rental markets are prevalent.

Second, interventions that facilitate capital sharing between firms can be promising, by reducing transaction costs in the rental market. This highlights one important benefit of industrial parks: in addition to providing easier access to infrastructure and knowledge spillovers, industrial parks can also facilitate the sharing of machines. To fully exploit the benefits of capital pooling, industrial parks should accommodate a mix of smaller and larger firms, as we have shown that larger firms are more likely to own and rent out machines. Other interventions linking entrepreneurs and facilitating the flow of information on supply and demand for machines may also be promising, such as business associations or informal networks of entrepreneurs.

Thirdly, and more broadly, our results show that to understand technology adoption in developing countries it is important to shift the focus away from the size of individual firms and towards the size and functioning of informal firm clusters; firm-to-firm interactions in the market for capital increase the effective firm size and are an essential driver of technology adoption.

This article summarizes ‘Achieving Scale Collectively’ by Vittorio Bassi, Raffaela Muoio, Tommaso Porzio, Ritwika Sen, and Esau Tugume, published in Econometrica in November 2022.

Vittorio Bassi is at the University of Southern California, the International Growth Centre (IGC), the Bureau for Research and Economic Analysis of Development (BREAD), and the Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR). Raffaela Muoio is at BRAC Uganda. Tommaso Porzio is at Columbia Business School, the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER), BREAD and CEPR. Ritwika Sen is at Northwestern University. Esau Tugume is at BRAC Uganda.