Summary

Can the spread of digital information and communication technology (ICT) foster mass political mobilization? There has been a wave of optimism about its use as a “liberation technology” capable of helping the oppressed and disenfranchised around the world. According to this argument, mobile phones and the internet have the potential to foster citizens’ political activism and even lead to mass political mobilization. Two mechanisms through which these effects may take place are increased information spreading and acquisition, and increased coordination.

On the other hand, governments can use this technology as a surveillance or propaganda tool— making protests less, rather than more, likely—and digital ICT can discourage the establishment of the ties that are instrumental to mass mobilization, which may ultimately lead to political apathy. The effect of mobile phones may also depend on the state of the economy; protests do not happen in a void, and worse economic conditions reduce the opportunity costs of protest participation and provide reasons for grievances.

Africa is one of the continents with the fastest rates of adoption in mobile phone technology, and has been the theatre of some of the most spectacular episodes of mass mobilisation over the last decades. We therefore use microdata on 2G mobile phone coverage and the occurrence of protest events across the African continent between 1998 and 2012 to empirically test whether mobile phone availability fosters or discourages protest activity at different points during the business cycle.

Despite the very detailed level of geographical disaggregation of our data, we include a very large set of area controls in our regression analysis to counteract the possible problem that protests and mobile phone adoption are spuriously correlated across areas of the same countries. We also propose and implement a novel instrumental variable strategy that exploits storm damage to mobile phone infrastructures; we use the variation on coverage adoption induced by differential levels of lightning activity across areas to derive causal estimate of the impact of mobile phones on protest activity.

We find strong and robust evidence that mobile phones are instrumental to mass political mobilization, although this only occurs during economic downturns. Our estimates imply that a one standard deviation fall in GDP growth leads to a differential increase in protests per capita between an area with full mobile phone coverage compared to an area with no coverage of between 8 and 23 percent, depending on the measure of protest used. The effects are particularly pronounced in urban areas, in areas with a legacy of conflict, in nondemocratic countries, and when traditional media are captured by the state. The analysis of microdata from the Afrobarometer indicates that each of the two impact mechanisms—increased information and increased coordination—account for around half of the reduced form effect.

These results suggest that, if appropriately used, digital technology has the potential to promote democratic progress. However, this analysis largely predates the period of adoption of 3G to 5G technologies. It remains to be seen whether the availability of these new technologies—which have increasingly allowed for access to the internet and social media—has had a different effect on citizens’ political participation. Calculating the overall effect of these new technologies on democratic progress is likely to be a first-order research topic for years to come.

Main article

The spread of digital information and communication technology has fed a wave of optimism about its use as a “liberation technology” capable of helping the oppressed and disenfranchised around the world. Using novel geo-referenced data on access to mobile technology and protest occurrence across the whole of Africa over fifteen years, we find evidence in favor of a nuanced version of this argument: mobile phones are instrumental to mass political mobilization, although this only occurs during economic downturns. Our results suggest that, if appropriately used, digital technology has the potential to promote democratic progress.

Can digital information and communication technology (ICT) foster mass political mobilization? In our 2020 Econometrica piece (Manacorda and Tesei, 2020), we use a variety of georeferenced data for the whole of Africa covering a 15-year span to investigate this question and explore channels of impact.

The spread of digital ICT has fed a wave of optimism about its use as a “liberation technology” capable of helping the oppressed and disenfranchised around the world. According to this argument, popularized by political sociologists and media scholars alike (Diamond 2010, Shirky 2011), mobile phones and the internet have the potential—thanks to the opportunity they offer for two-way, multi-way, and mass communication, and their low-cost, decentralized, open-access nature—to foster citizens’ political activism and even lead to mass political mobilization, especially when civic forms of political participation are de facto or lawfully prevented.

In particular, increased information and communication enabled by mobile phones have the potential to trigger collective action through information spreading and acquisition. By granting access to unadulterated information, digital ICT also has the potential to offset government propaganda, which can curb discontent via misinformation and persuasion, especially when media are under the control of the government or other interest groups (Edmond 2013). This effect is reinforced when strategic complementarities are at play: when the returns to political activism increase or the costs of participation decrease with the number of others participating (Barbera and Jackson 2017, Passarelli and Tabellini 2017), mobile phone technology can foster mass mobilization through increased citizens’ coordination.

On the other hand, governments can use this technology as a surveillance or propaganda tool, making protests less, rather than more, likely (Morozov 2012). Digital ICT can also discourage social capital accumulation and the establishment of “strong ties” that are instrumental to mass mobilization (Gladwell 2010), ultimately leading to political apathy.

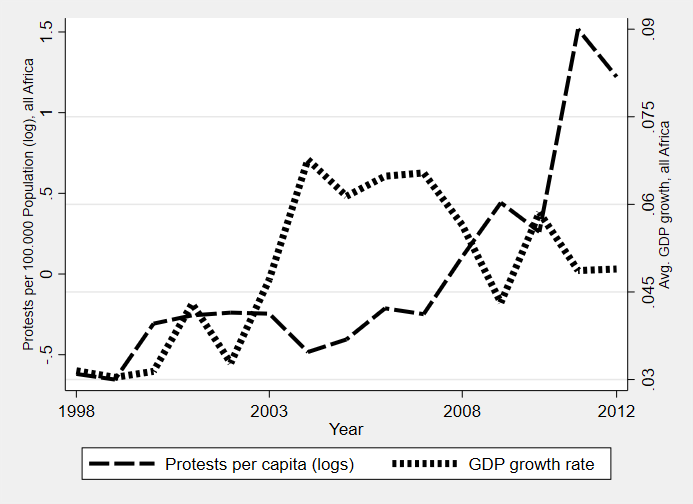

An additional consideration is that while the “liberation technology argument” suggests that protests should arise in response to the availability of mobile phones, protests do not happen in a void and tend to be particularly likely during economic downturns (Figure 1). This is because worse economic conditions reduce the opportunity costs of protest participation and provide reasons for grievances. This suggests that if mobile phones play a role in fostering protest provision, this effect would likely be stronger during economic downturns, when an independent trigger for protests exists.

Figure 1. The Evolution of Protests across the Business Cycle

Hence, whether mobile phone availability fosters or discourages protest activity, and whether this effect is the same at different points during the business cycle, remain open empirical questions. With the exception of a few studies that focus on the role of the internet and social media in protest participation (Acemoglu et al. 2014 for Egypt; Enikolopov et al. 2015 for Russia), a large body of research has focused on the effect of traditional media and the internet on civic forms of participation such as voting (Gentzkow 2006, Falck et al 2014).

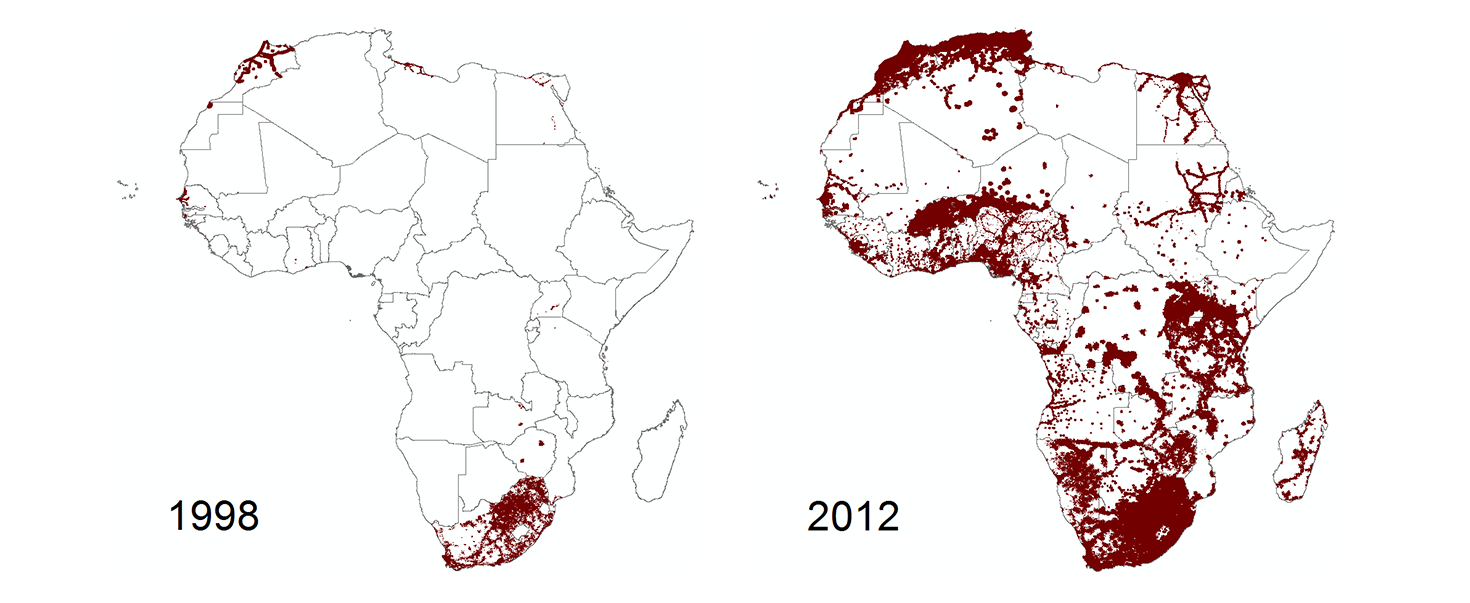

In order to subject this argument to empirical scrutiny, we focus on Africa, one of the continents with the fastest rates of adoption in mobile phone technology (Figure 2) and the theatre of some of the most spectacular episodes of mass mobilisation over the last decades (food riots swept the continent between 2007 and 2008 and mass civil unrest—the Arab Spring—erupted in the northern countries between 2010 and 2012). Importantly, mobile phone technology adoption in many countries in the continent happened against the backdrop of a practically non-existent fixed line infrastructure. As a result, it is claimed that mobile adoption has had unprecedented consequences on the life of African citizens, especially the poor (Aker and Mbiti 2010).

Figure 2. Trends in Mobile Phone Coverage across Africa, 1998-2012

Key challenges

One obvious empirical challenge in addressing the research question is that access to ICT technology and protest occurrence are likely correlated for reasons other than the causal effect of the former on the latter. This could happen, for example, if a country’s economic prosperity leads to a faster rate of technology adoption as wells as to lower protests. In this case one would likely underestimate the effect of access to mobile technology on protest occurrence. This empirical challenge clearly illustrates the pitfall of inference based on “macro”comparisons across countries or across countries and time.

In order to circumvent this problem, we leverage novel licensed microdata on local 2G mobile phone coverage from the Global System for Mobile Communications Association (GSMA). We combine this with microdata on the occurrence of protest events based on compilations of news wires, which effectively refer to the entire continent between 1998 and 2012. The advantage of the datasets that we assembled is their level of geographical detail. GSMA data provide information on mobile phone signal availability at a level of geographical precision of between approximately 1 and 23 km2 on the ground, depending on the country. Protest data from the Global Database on Events, Location and Tone (GDELT, Leetaru and Schrodt 2013)—a large, open-source data set relying on an automated textual analysis of news sources—provide precise coordinates on the location of protest events. We also manually compiled data on protest occurrence from other sources (the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project, ACLED, Raleigh et al. 2010, and the Climate Change and African Political Stability (CCPAS) Social Conflict Analysis Database, SCAD, Salehyan et al. 2012) to corroborate data from GDELT; these data sources also provide precise coordinates of such events, although they list significantly fewer—and likely bigger—events.

The very detailed level of geographical disaggregation of the data allows us to compare changes in the incidence of protests across very small areas within the same country. This alleviates the concern that our estimates of impact capture a spurious correlation between mobile phone coverage and protests across countries and time. Moreover, the high level of geographical detail and the relatively long time span of our data allow us to estimate differential effects across areas with different characteristics as well as at different point along the business cycle.

Despite the granular geographical variation of our data, one might still be concerned that protests and mobile phone adoption are spuriously correlated across areas of the same countries. For example, urban areas might be more likely to see faster technology adoption while also being more likely to see mass gatherings and protests. To circumvent this problem and rule out non-random assignment of mobile signal to cells with different latent propensity in protest activity, we include a very large set of area controls in our regression analysis. As one might still be concerned that such controls do not adequately account for all spurious differences in protest activity across areas with different intensity of ICT investment, we also propose and implement a novel instrumental variable strategy that exploits the circumstance that frequent electrostatic discharges during storms damage mobile phone infrastructures and negatively affect connectivity (Andersen, Bentzen, Dalgaard, and Selaya 2012; ITU 2003), hence discouraging adoption. Using National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) satellite-generated data, we show indeed that areas with higher-than-average incidence in lightning strikes display slower adoption of mobile phone technology over the period. We hence use the variation on coverage adoption induced by differential levels of lightning activity across areas to derive causal estimate of the impact of mobile phones on protest activity.

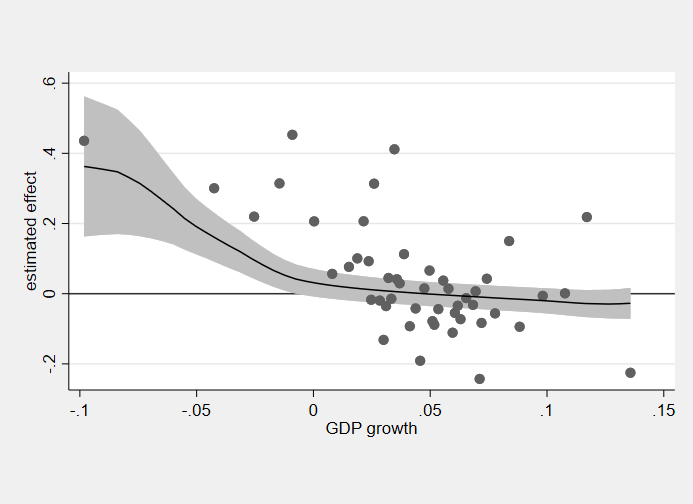

In line with the nuanced version of the “liberation technology argument,” we find strong and robust evidence that mobile phones are instrumental to mass political mobilization, although this only occurs during economic downturns. In order to get a sense of magnitudes, our estimates imply that a one standard deviation fall in GDP growth (approximately 4 percentage points) leads to a differential increase in protests per capita between an area with full mobile phone coverage compared to an area with no coverage of between 8 and 23 percent, depending on the measure of protest used. Effects manifest exclusively during recessions, while we find no effects during good economic times. This is clearly evident in Figure 3, which shows the relationship between protests and predicted mobile phone coverage (as induced by our instrument) at different levels of GDP growth.

Figure 3. Mobile Phone Coverage and Protests: Heterogeneous Effects by Levels of GDP Growth

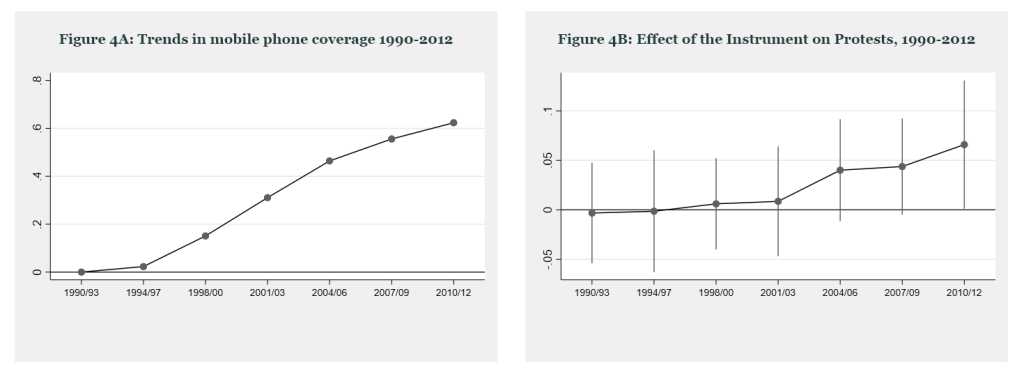

In order to corroborate a causal interpretation for our estimates, we show in Figure 4 that our instrument is uncorrelated with protests in periods when mobile phone technology was unavailable, suggesting that the effect of lightning strikes on protest is credibly attributable to the mediating effect of mobile phone coverage.

Figure 4.

We also uncover relevant dimensions of heterogeneity, with the effects being particularly pronounced in urban areas, in areas with a legacy of conflict, in nondemocratic countries, and when traditional media are captured by the state.

We finally complement the analysis with microdata from the Afrobarometer, which provide individual-level information on protest participation, as well as precise area of residence for a subset of countries/years. Remarkably, results based on microdata closely mimic those obtained using information on protest occurrence from newswires. These data also allow us to shed some light on the mechanisms of impact and quantify their role. In line with the two mechanisms of impact highlighted above—increased information and increased coordination—and guided by theory, we show that both mechanisms are at a play, each accounting for about half of the reduced form effect we uncover.

Policy implications

Our analysis suggests that ICT, and in particular the ubiquitous use of mobile phones for calling and messaging, indeed helped promote mass mobilisation and possibly democratic progress in Africa, especially when reasons for grievance existed and citizens had reasons to blame the government for the poor state of the economy. Of course, the question that naturally arises is why governments allowed this technology to spread when this led to mass civil unrest, which is clearly costly and can even lead to the government being toppled. The answer is straightforward: there are of course economic gains to this technology (which we do not study) and potentially political returns for incumbent governments. Governments will likely offset the political costs with the potential gains when deciding whether to promote this technology.

We should also caution a reader that our analysis refers to the period when 2G technology spread very fast and it largely predates the period of adoption of 3G to 5G technologies, which have increasingly allowed for access to email, mobile internet, and social media. The question then is whether the effects we uncover during the transition to full mobile phone coverage are still at a play, and whether the availability of new technologies has had a different effect on citizens’ political participation, as well as government responses.

A growing body of research has recently turned to studying the effect of mobile internet on voting outcomes. In particular, Guriev, Melnikov and Zhuravskaya (2021) shows that 3G mobile signal has reduced citizens’ confidence in governments worldwide and reduced chances of the incumbent’s re-election, while Manacorda, Tabellini and Tesei (2023) shows that these technologies have increased support for extreme right-wing communitarian parties in Europe. It is probably still too early to say what, overall, these technologies have implied for democratic progress around the world; this is likely to be a first-order research topic for the years to come.

This article summarizes ‘Liberation technology: Mobile phones and political mobilization in Africa’ by Marco Manacorda and Andrea Tesei, published in Econometrica in March 2020.

Marco Manacorda is a Professor of Economics and Public Policy at Queen Mary University of London. His research interests and expertise are at the intersection of political economy, labour, development and public economics. Andrea Tesei is a Reader at Queen Mary University. His research interests are in political economy and development economics.