Summary

Productivity growth often relies on productive firms gaining resources compared to less productive firms, in a process of “creative destruction”. But can incumbent firms use political connections to impede this reallocation? A recent study shows how the political connections of Italian firms influence firm growth, innovation, and aggregate productivity. The research combines theoretical insights with empirical analysis of a new large-scale dataset on firms and politicians. The researchers identify a leadership paradox: market leaders are much more likely to be politically connected, but much less likely to innovate. Political connections are associated with a higher rate of firm survival, and growth in employment and revenues, but not gains in productivity or innovation. When looking at the overall impact, political connections can help firms overcome bureaucratic hurdles, but this does not fully compensate for slower reallocation and growth.

When a market economy is working well, economic resources are continually reallocated from less productive incumbents to more productive innovative firms. Then, competition thrives, firms innovate, the economy grows, and consumers benefit. Yet slow productivity growth and declining business dynamism have become concerns in the US and some other OECD member countries. The research summarized here shows how close links between firms and local politicians have undermined economic performance in the case of Italy. This may help to explain why recent productivity growth has been lackluster.

Italy is an especially interesting case to study because, after a series of corruption scandals, it gave more power to local bodies and politicians. Firms may choose to develop connections with these politicians to overcome market “frictions”, such as red tape and regulations. But when established companies come to rely on political ties to maintain their market dominance, they may no longer need to compete through innovation. Studying the data, the researchers identify a leadership paradox: market leaders are indeed more likely than their direct competitors to be politically connected, but less likely to innovate.

To examine this in more detail, the researchers use data on firm performance, local politicians, and local election outcomes. The usefulness of given political connections will change depending on which politicians gain or lose power. The researchers study the aftermath of close elections in particular. Firms connected to losing politicians in tightly contested elections do especially badly, while firms on the winning side are more likely to grow larger. Differences in productivity growth are not found, however. This suggests that political connections can shield firms, without leading them to become more productive.

The researchers combine their data analysis with an economic model to estimate the consequences of political connections for the economy as a whole. When firms make connections with politicians, the easing of regulatory and bureaucratic burdens helps those firms, and increases aggregate output by 1.2%. But those benefits are more than offset by wider social costs, since connected firms have less need to innovate. The researchers find that political connections undermine creative destruction and productivity growth, and this reduces the present value of aggregate output by 3%. More research, using similarly rich datasets in other settings, will be needed to better understand the role of political influence in declining business dynamism and slower growth, and the policies that could reverse those trends.

Main article

When the “gale of creative destruction” leads to the reallocation of economic resources from less productive incumbents to more productive innovative firms, competition thrives, innovation increases, the economy grows, and consumers benefit. But many market frictions, such as red tape and regulations, may impede this process and the churning of firms. The outcome is lower business dynamism and sluggish productivity growth. And if established companies come to rely on political ties to maintain their market dominance, they may no longer need to compete through innovation.

If established companies come to rely on political ties to maintain their market dominance, they may no longer need to compete through innovation.

Recently, researchers and policymakers have become concerned about the growing dominance of large firms, declining business dynamism, and slower productivity growth in the US and other OECD member countries (Decker et al. 2016; De Loecker and Eeckhout 2018). At the same time, political “rent-seeking” has increased (Zingales 2012; Bessen 2016). In the research we summarize here (Akcigit et al. 2023), we study how the political connections of firms influence firm dynamics, innovation, and aggregate productivity. The research combines theoretical insights with empirical analysis of a new large-scale dataset on firms and politicians in Italy.

Italian institutional context

A wealth of anecdotal evidence points to the connections between political influence and the corporate sector in Italy. One especially prominent illustration comes from the historical episode known as “Mani Pulite” or “Clean Hands”, an investigation during the early 1990s that exposed a vast network of corruption and bribery across Italy.

In the aftermath of one of the largest anti-corruption operations in the world, numerous state reforms were put into practice, prompted by these scandals. The reforms aimed to bring decision-making power closer to citizens, in an effort to safeguard politicians from undue influence. This transpired in a stratification of decision-making levels and significant differences across regions in the effectiveness of central public administration, local regulations, and their enforcement.

Within each narrowly-defined market… the market leaders are more likely than their direct competitors to be politically connected.

The process resulted in the creation of nearly 130 thousand regional, provincial, and municipal elected positions, leading to more than 500 thousand individuals serving as local politicians over the subsequent 20 years. As a result of these decentralization efforts, local politicians at the municipal, provincial, and regional levels gained extensive powers (Vannucci 2009). Local politicians hold several key responsibilities, including overseeing the provision of local public goods and services, exercising administrative control over the issuance of permits and licenses, and bearing the primary responsibility for managing most of the administrative burdens that private firms encounter in Italy.

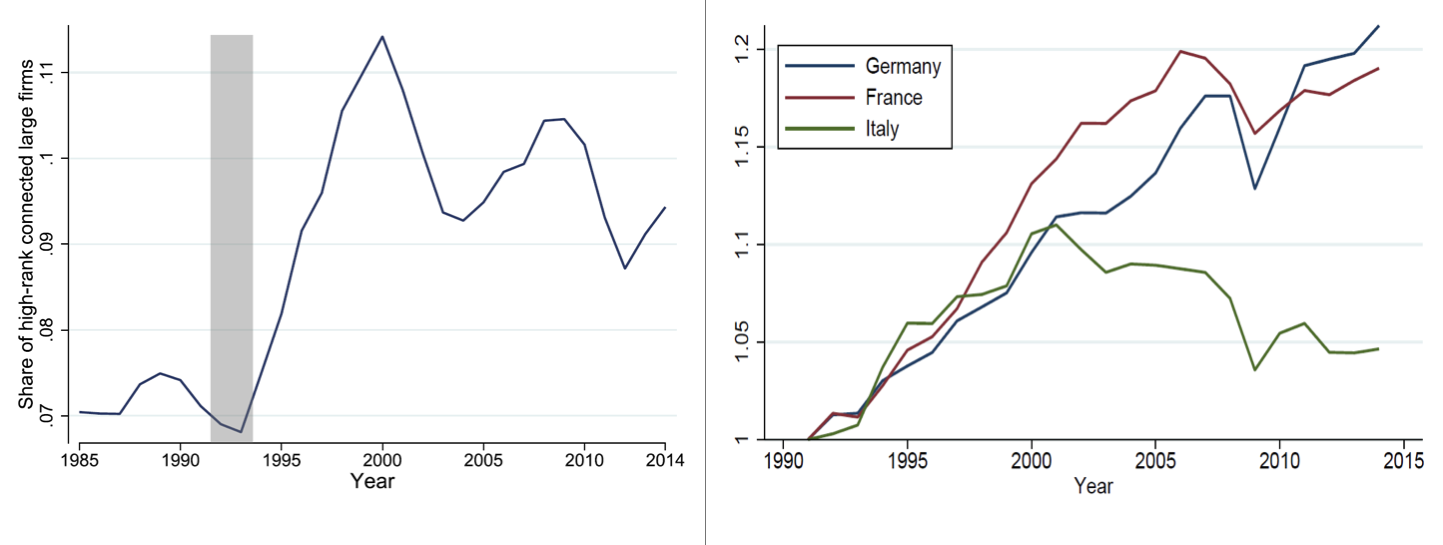

At the same time, Italian bureaucratic efficiency has been steadily worsening (Gratton et al. 2017). As a result, in an environment with growing regulations and burdensome bureaucracy, local politicians became important in helping firms “navigate the system.” Indeed, as Figure 1 shows, the share of large firms (more than a hundred workers) employing local high-rank politicians (e.g., mayors, vice-mayors, council presidents) grew sharply after the reforms of the early 1990s.

Italian productivity then began to stagnate (Figure 2). While many forces could be at play in low and stalling aggregate productivity, we try to shed light on what firm-level political connections imply for firm dynamics, innovation incentives, and competition.

Figures 1 and 2

Notes to Figure 1: This figure plots the average share over time of firms that are politically connected with high-rank politicians, among the firms with more than a hundred employees. High-rank politicians are mayors or vice-mayors, province or regional presidents or vice-presidents, or presidents or vice-presidents of local councils.

Notes to Figure 2: TFP series for France, Germany, and Italy. The series are normalized to one in 1991. Source: AMECO Database.

The more an industry is subject to bureaucracy or regulatory burdens, the more pervasive are connections in that industry.

New data

We define a firm as being politically connected in a particular year if the firm employs at least one local politician in that year, as in Cingano and Pinotti (2013). Thanks to a newly available data set from the Italian Social Security office on the universe of firms and the employment histories of all private-sector workers from 1993-2014, we can measure the scale of firm-level political connections for the universe of Italian firms, to better understand the micro and macro implications of these connections.

We combine these data with the national registry of local politicians, which has information on all politicians at the municipal, provincial, and regional levels, and with local elections data. Overall, there are 515 thousand politicians in the data during this time period. The largest majority of them serve at the municipality level, with about two-thirds being council members, and others holding higher-rank executive positions, such as executive councilor, mayor, vice-mayor, provincial or regional president or vice-president.

Since local politicians can also work in the private sector while they hold office, we observe many politicians on the payroll of private companies, allowing us to identify political connections. Firm-level political connections are widespread in Italy, especially among larger and older firms. The average share of connected firms by industries is 4.5%. Across all industries, connected firms account for a third of employment.

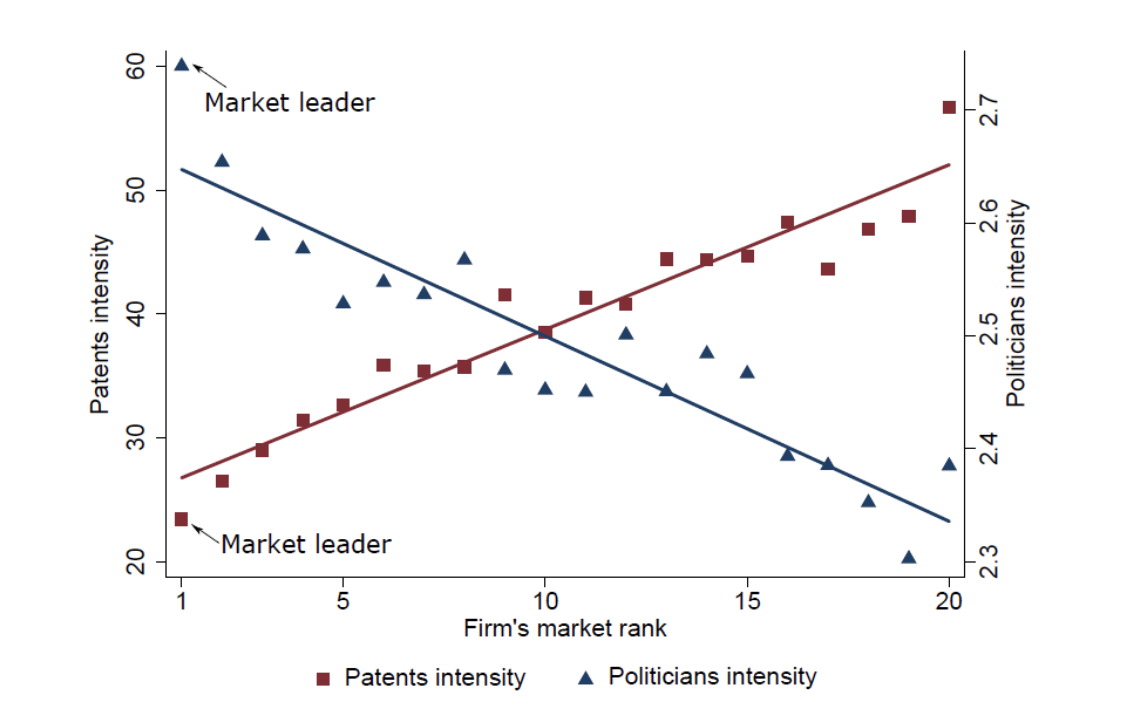

A leadership paradox

Market competition creates tensions between the market leader and its competitors. While followers try to surpass the leader with new products or technological innovation, the leader may often rely on various defensive strategies to maintain its market position. These defensive strategies could include the establishment of political connections. In our empirical analysis, we identify a leadership paradox (Figure 3). Within each narrowly-defined market, at a six-digit industry-region-year level, the market leaders are more likely than their direct competitors to be politically connected – measured in this figure as the number of politicians normalized by firm size. But they are less likely to innovate, measured by the quantity and quality of patents, and by investment in intangible capital, all normalized by firm size.

Figure 3

Notes to Figure 3: Figure plots politician intensity and innovation intensity over the firm’s market rank for the top 20 firms in each market. The market is defined at the six-digit industry-region-year level. Politician intensity (blue triangles) is the number of politicians employed in a firm normalized by 100 white-collar employees. Innovation intensity (red squares) is the number of patent applications in a year normalized by 100 white-collar employees (conditional on patenting). Both outcome variables are adjusted for industry, region, and year “fixed effects” to control for variation specific to particular industries, regions or years.

Firm outcomes

Although politically connected firms are less likely to innovate, they are more likely to survive in the market and to see higher growth in revenues and employment. The growth effect is more marked when the firm is linked to politicians with more power, but the growth in firm size is not coupled with growth in productivity.

Dynamic losses, caused by the effects of political connections on creative destruction and productivity growth, outweigh the static benefits.

These growth differentials are also visible when we focus on the performance of connected firms around tightly contested elections. Using data on all local elections in Italy, including voting outcomes, we identify elections that were decided on a thin margin: for example, a 51%-49% vote split. The win/loss outcomes of these very close elections can be considered as rather like a coin flip, originating in breaking news, weather shocks, and so on.

This implies that firms connected in the run-up to these elections with a politician from marginally losing, versus marginally winning, parties/coalitions at the next election are likely to be similar on average. For example, they should have similar expectations about upcoming election outcomes. We find that post-election outcomes differ between marginally winning and marginally losing firms. The performance of firms connected to losing politicians in very tightly contested elections is especially bad. As a result, firms are more likely to grow larger when on the winning side rather than the losing side. Differences in productivity growth are not found, however. These findings suggest that political connections help firms to overcome particular market frictions – such as helping with red tape or addressing regulations – or block competition, as opposed to helping them advance the frontiers of productivity and technology.

We also observe that worker-politicians earn significant wage premiums relative to their co-workers, not explained by their individual observable characteristics. This premium increases with the political rank of a worker-politician. Hence, certain benefits that accrue to firms are partly shared with their politician-employees.

Aggregate outcomes

If we look at a more aggregate level, political connections tend to be associated with weaker market dynamics – lower entry, reallocation, growth, and productivity. This indicates that the effects of firm-level political connections go beyond the micro-level effects on connected firms and may imply significant social costs.

We measure the bureaucratic and regulatory burden on each industry and combine it with regional data on institutional quality, so that we can examine the importance of bureaucratic and regulatory frictions for the use of political connections. We find that, the more an industry is subject to bureaucracy or regulatory burdens, the more pervasive are connections in that industry. The use of political connections, and a negative relationship between connections and business dynamism, are particularly strong in heavily regulated industries and regions with poor institutional quality – that is, low regulatory quality and control of corruption.

Static gains, dynamic losses

To understand the issues further, we analyze a theoretical model of how political connections could influence an economy’s business dynamism, new firm creation, and innovation. In the model, firms face bureaucratic and regulatory burdens that may be alleviated by connecting with politicians. The model underscores two opposing insights on the desirability of political connections for the economy. At a point in time, political connections may be beneficial by smoothing out the effects of bureaucratic frictions; these are “static” gains. But over time, the political influence of incumbents gives them an advantage over other market participants, lowering creative destruction and innovation overall. These are “dynamic” losses.

Using the model and our data, we provide approximate back-of-the-envelope estimates of these static gains and dynamic losses from the presence of political connections in Italy. First, we estimate that bureaucratic and regulatory costs are substantial, causing an aggregate output loss of 4% relative to the economy with no such costs.

Political connections that ease regulatory and bureaucratic burdens for connected firms lead to a 1.2% static gain in aggregate output. However, dynamic losses, caused by the effects of political connections on creative destruction and productivity growth, outweigh the static benefits: they reduce the present value of aggregate output by 3%.

Conclusions

At least in Italy, the use of political connections among market leaders is common. Our research shows how these connections have negative consequences for aggregate dynamics, due to inefficient reallocation. Political influence is one of the growth strategies of market leaders. This results in the persistent dominance of incumbent firms, making the economy less innovative overall.

Recent evidence on increasing market concentration and declining business dynamism in the US and other OECD member countries, together with an increase in lobbying, suggests that the facts we document in the Italian context may also be present elsewhere. More work – both theoretical and empirical, with similarly rich new datasets in other settings – can help us better understand the quantitative importance of political influence for declining trends in business dynamism, and the policies that could reverse those trends.

This article summarizes ‘Connecting to Power: Political Connections, Innovation, and Firm Dynamics’ by Ufuk Akcigit, Salome Baslandze, and Francesca Lotti, published in Econometrica in March 2023. Ufuk Akcigit is Arnold C. Harberger Professor of Economics at the University of Chicago. Salome Baslandze is a Research Economist and Assistant Adviser at the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta. Francesca Lotti is a Director in the DG Economics, Statistics and Research of the Bank of Italy.