Summary

Capital misallocation, which occurs when investments don’t flow to the businesses that could use them most productively, can limit economic growth. However, improving the allocation of capital is challenging as we have limited evidence about which policies effectively reduce misallocation and even measuring misallocation accurately has proven difficult.

Our research examines a unique set of reforms in India that help address both these challenges. In response to a financial crisis in 1991, India began gradually opening its economy. In 2001 and 2006, the government liberalized foreign direct investment in specific industries. These policies create a natural experiment as we can compare how outcomes changed over time for businesses in industries that were opened to foreign investment versus those that remained restricted. Furthermore, we can identify firms that appeared to have too little capital prior to the reforms and see if these firms were differentially affected by the reforms. If treated firms that ex-ante appeared capital constrained grew following the reforms (relative to similar firms in non-reformed industries), this is evidence that the capital allocation improved. Our dataset is representative of large and medium-sized Indian firms.

We find three major results:

- Businesses in industries opened to foreign investment grew substantially, increasing their physical assets by approximately 32%. Importantly, there is no differential effect of being in a reformed industry prior to the year the reform took place, indicating that the outcomes of firms in reformed industries were not simply evolving differently.

- This growth was not uniform. We ranked firms based on their pre-reform marginal revenue product to capital (MRPK) and then separately estimate the effects of the reform for firms that have above and below average MRPKs prior to the reform within their industries. Relative to non-constrained treated firms, capital constrained firms expanded their assets by approximately 53%, increased their workforce spending by approximately 28%, and grew their revenue by approximately 23%. In contrast, firms that we identify as capital-unconstrained in the deregulated industries did not expand relative to similar firms in non-deregulated industries.

- These improvements benefited consumers, as well as businesses. The firms that gained better access to capital reduced their prices by approximately 21% on average, and the previously capital constrained treated firms also increased their product offerings.

Using a new method based on the decomposition of changes in the Solow residual, we show that, under reasonable assumptions in our setting, the more inefficient the initial allocation of capital was, the larger the potential gains from the reform would be. On aggregate, we estimate that India’s gradual opening up to foreign capital increased a proxy for aggregate productivity in the affected manufacturing industries by 3-16%. Even at the conservative end of this range, this represents a substantial improvement in productivity. Thus, FDI liberalization significantly improved productivity by improving the allocation of capital in India.

Access to foreign capital remains highly regulated in many low-income countries, and our results therefore indicate that FDI liberalization is a policy tool that could be used to significant effect—both in India, where half of firms within the manufacturing sector are in industries that still have not been reformed, and elsewhere. We do find, however, that the development of domestic banking markets plays an important role in determining the policy’s effects.

Main article

Capital misallocation—which occurs when investments don’t flow to the businesses that could use them most productively—can limit economic growth. To date, there has been limited evidence on what policies effectively reduce misallocation. Our results use a natural experiment in India to demonstrate that FDI liberalization can increase the physical assets of businesses that were previously capital constrained, decreasing misallocation and significantly improving productivity. Access to foreign capital remains highly regulated in many low-income countries, and our results therefore indicate that FDI liberalization is a policy tool that could be used to significant effect.

Why do some countries remain significantly poorer than others? Research shows that a key factor is how efficiently they use their resources, including capital—the physical assets, such as plants and machinery, used in production. Misallocation occurs when investments don’t flow to the businesses that could use them most productively. Reallocating capital to more productive uses could therefore help unlock economic growth.

Capital misallocation occurs when investments don’t flow to the businesses that could use them most productively.

Despite the importance of misallocation in limiting growth, improving the allocation of capital is challenging for two major reasons. First, we have limited evidence about which policies effectively reduce misallocation and help resources flow to the right businesses. This is particularly crucial for developing countries, where the misallocation of capital is likely to be substantial. Second, measuring misallocation accurately has proven difficult. Traditional measurement methods might overstate the problem, which could lead policymakers to pursue costly policies with limited benefits.

A Natural Experiment in India

Our research examines a unique set of reforms in India that help address both these challenges. These reforms provide clear evidence about how opening markets to foreign investment can improve capital allocation.

Our research examines a unique set of reforms in India, which provides clear evidence about how FDI liberalization can improve capital allocation.

In response to a financial crisis in 1991, India began gradually opening its economy. In 2001 and 2006, the government liberalized foreign direct investment in specific industries, allowing automatic approval of foreign investments up to (at least) 51% ownership. These policies create a natural experiment. We can compare how outcomes changed over time for businesses in industries that were opened to foreign investment versus those that remained restricted. By comparing changes over time instead of differences in the levels of firms’ outcomes, we control for pre-existing differences between reformed and unreformed industries. Furthermore, we can identify firms that appeared to have too little capital prior to the reforms and see if these firms were differentially affected by the reforms. If treated firms that ex-ante appeared capital constrained grew following the reforms (relative to similar firms in non-reformed industries), this is evidence that the capital allocation improved.

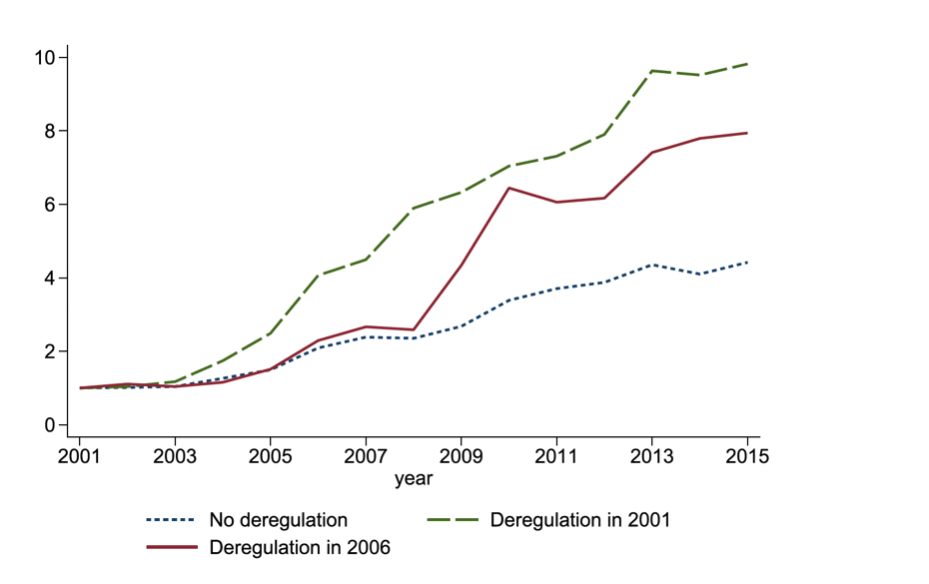

The reforms of 2001 and 2006 increased foreign capital in the targeted industries in the years following the deregulation (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Flow of foreign equities among liberalized and non-liberalized industries

Note: This figure plots the overall amount of foreign equity in Prowess, India’s largest corporate database, for industries that have deregulated in 2001 (the red line), in 2006 (the green line), or whose regulation did not change during the period 1995–2015 (the blue line). The flows are normalized to 1 in 2001.

To measure the effects of foreign capital liberalization, we combine this policy experiment with firm-level data from Prowess, India’s largest corporate database, compiled by the Centre for Monitoring the Indian Economy (CMIE). The dataset contains information from the income statements and balance sheets of companies comprising more than 70% of the economic activity in the organized industrial sector of India. Thus, it is representative of large and medium-sized Indian firms.

Main Findings: Capital Allocation Improved

There are three major results:

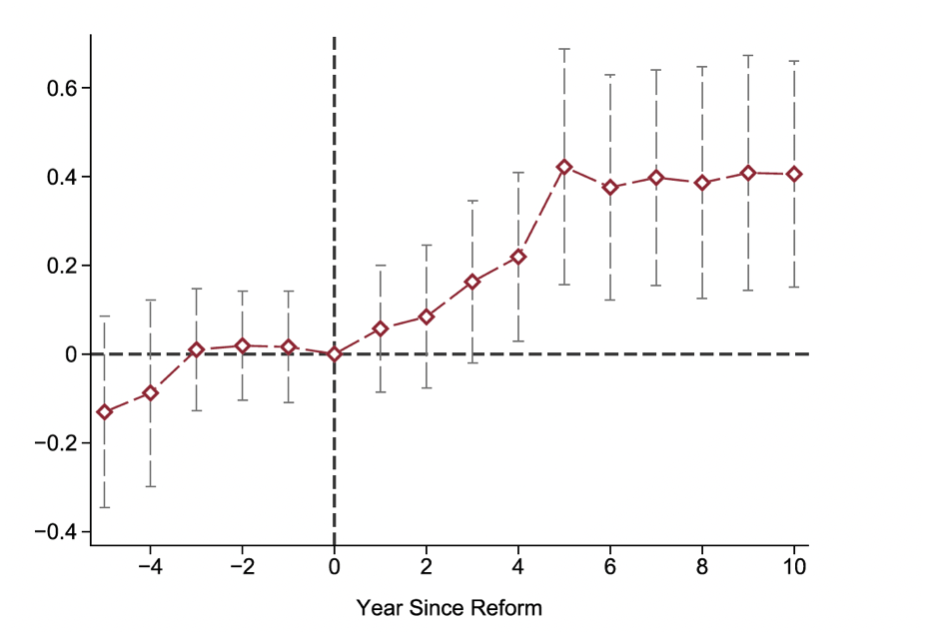

First, businesses in industries opened to foreign investment grew substantially, increasing their physical assets by approximately 32% (Figure 2). That is, the increase in foreign equity in treated industries shown in Figure 1 translated into an increase in physical assets used in production. Figure 2 reports the average effect of being in a treated industry by year around the reform, with the year prior to the year during which an industry was reformed normalized to be 0. Importantly, there is no differential effect of being in a reformed industry prior to the year the reform took place, indicating that the outcomes of firms in reformed industries were not simply evolving differently. Rather, their outcomes only deviate from those of firms in non-reformed industries in the year of the reform, after which their capital levels grow before plateauing at a permanently higher level around 5 years after the reform.

Figure 2: Event study graph for the average effect of foreign capital liberalization on physical capital

Note: This figure reports the event study graph for the average effect of the liberalization on firms’ physical capital. The dependent variable is in logs. The reform is normalized to take place in year 1. Each dot is the coefficient on the interaction between being observed t years after the reform and being in a treated industry. The confidence interval is at the 95% level.

Businesses in industries opened to foreign investment grew substantially, increasing their physical assets by approximately 32%.

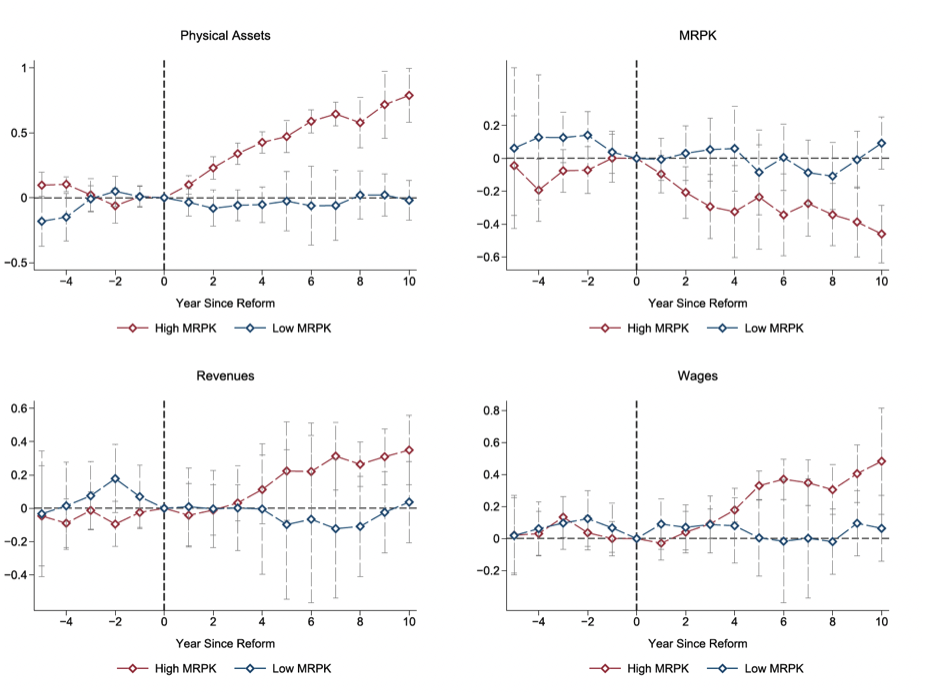

Second, and more importantly, this growth wasn’t uniform. To uncover the effect of the reform on misallocation, we estimate the differential effect of the reform on firms that were ex-ante capital constrained compared to those that were not.

To do so, we rank firms based on their pre-reform marginal revenue product to capital (MRPK). MRPK is the measure of the revenues created when a firm uses an additional unit of capital. It is often used to measure the degree of the capital constraints faced by a firm since resources should flow to the firms with the highest returns. Therefore, a firm ‘stuck’ with a large return on investment is likely to be prevented from growing because it faces a high cost of capital, leading to misallocation. We then separately estimate the effects of the reform for firms that have above and below average MRPKs prior to the reform within their industries.

We find that the businesses that benefited most from the reforms were those that were previously capital constrained. Relative to non-constrained treated firms, these firms:

- Expanded their assets by approximately 53%;

- Increased their workforce spending by approximately 28%;

- Grew their revenue by approximately 23%.

This indicates that the cost of capital fell for firms with initially high costs of capital. The fact that capital increased for the previously capital-constrained firms indicates that capital misallocation also fell. In contrast, firms that we identify as capital-unconstrained in the deregulated industries did not expand relative to similar firms in non-deregulated industries (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Separate event studies for constrained and unconstrained firms

Note: This figure reports the effect of FDI liberalization for high and low MRPK firms separately for physical assets, MRPK, revenues, and the wage bill. The dependent variables are in logs. The reform is normalized to take place in year 1. Each dot is the coefficient on the interaction between being observed t years after the reform and being in a treated industry. The confidence interval is at the 95% level.

Our results are quantitatively unchanged when we perform a large battery of robustness tests, such as controlling for more firm characteristics, controlling for contemporaneous shocks like changes in dereservation laws or tariff changes, or accounting for the input-output spillovers. These results also remain broadly unchanged when we use a different dataset that includes smaller formal sector firms, the Annual Survey of Industry (ASI).

We find that the businesses that benefited most from the reforms were those that were previously capital constrained.

Third, these improvements weren’t just good for businesses: they benefited consumers too. The firms that gained better access to capital reduced their prices by approximately 21% on average, and the previously capital constrained treated firms also increased their product offerings.

The Role of Local Financial Markets

Why did opening up to foreign capital matter so much for misallocation in India? And should we expect the same effects in other countries?

Our research suggests that the success of foreign investment reforms depends significantly on local financial conditions. Since India is a federal country, with much of the regulation of its banks and bankruptcy procedure decentralized at the state level, we can exploit the vast geographic disparities in how easily firms can access bank credit.

[Improvements] benefited consumers too… the firms that gained better access to capital reduced their prices by approximately 21% on average.

We find that local capital markets play an important role in determining the policy’s effects. When we compare firms located in states at the first quartile of the domestic financial development distribution with firms located in states in the top quartile, we find that the effect of opening up to foreign investment on capital constrained firms’ capital is three times greater.

Therefore, the effects of opening up to FDI on misallocation are linked to the development of domestic banking markets.

Quantifying the Aggregate Effect of the Liberalization

To measure the overall economic effects of FDI liberalization, we developed a new method based on a decomposition of changes in the Solow residual introduced by Petrin and Levinsohn (2012) and Baqaee and Farhi (2019), that connects our firm-level findings to a proxy for the aggregate productivity of treated industries. This method has two key advantages over traditional approaches: it requires fewer assumptions about how the economy works, and it is less likely to overstate the benefits of the policy.

Our approach uses two crucial pieces of information: first, how individual firms changed their inputs in response to the policy (which we measure directly using the natural experiment), and second, how inefficiently inputs were allocated before the reform (which is harder to measure precisely).

The decomposition shows that, under reasonable assumptions in our setting, the more inefficient the initial allocation of capital was, the larger the potential gains from the reform would be. If we assume the reform reduced misallocation, in line with our natural experimental estimates and the large baseline dispersion in MRPK, the smallest possible level of baseline inefficiency is identified by the changes in firms’ MRPKs due to the policy, which we can also estimate using the natural experiment. This allows us to establish a lower bound for the policy’s impact.

We estimate that opening up to foreign capital increased a proxy for aggregate productivity in the affected manufacturing industries by 3-16%.

To establish an upper bound, we attribute all of the pre-treatment cross-sectional variation in marginal revenue products of inputs to misallocation. While some of these differences reflect real inefficiencies that could be improved by policy, others might simply reflect measurement problems or other factors our analysis can’t capture.

Using this approach, we estimate that opening up to foreign capital increased a proxy for aggregate productivity in the affected manufacturing industries by 3-16%. Even at the conservative end of this range, this represents a substantial improvement in productivity. Thus, FDI liberalization significantly improved productivity by improving the allocation of capital in India.

Access to foreign capital remains highly regulated in many low-income countries, and our results therefore indicate that FDI liberalization is a policy tool that could be used to significant effect—both in India, where half of firms within the manufacturing sector are in industries that still have not been reformed, and elsewhere.

This article summarizes ‘Misallocation and Capital Market Integration: Evidence From India’ by Natalie Bau and Adrien Matray, published in Econometrica in January 2023.

Natalie Bau is at the Department of Economics at UCLA. Adrien Matray is at the Department of Economics at Princeton University.

References

Baqaee, David, and Farhi, Emmanuel (2019): “A Short Note on Aggregating Productivity,” NBER Working Paper. [69,73]

Petrin, Amil, and Levinsohn, James (2012): “Measuring Aggregate Productivity Growth Using Plant-Level Data,” The RAND Journal of Economics, 43, 705–725. [69,73]